For Centuries, People Celebrated a Little Boy’s First Pair of Trousers

Literally a party in your pants.

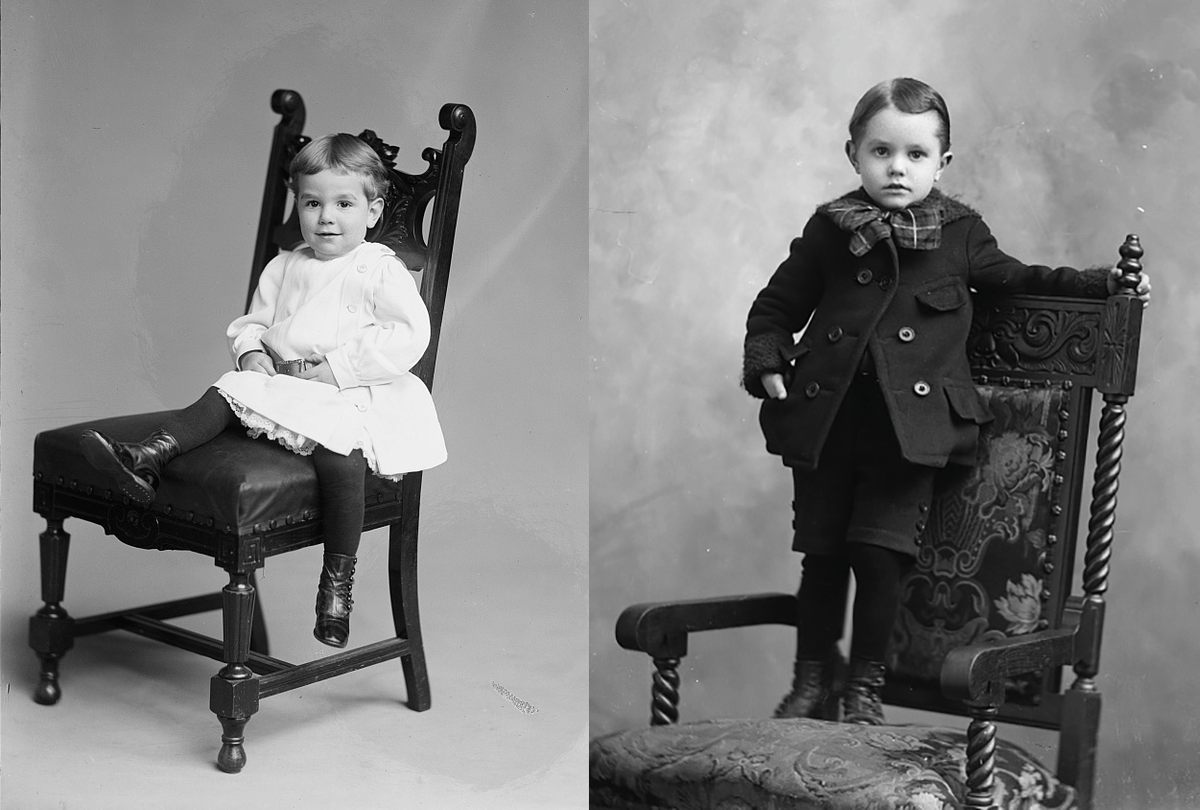

John Neal, an 18th-century resident of post–Revolutionary War America, remembered the day that he and his twin sister were torn asunder. “They put me into jacket and trousers,” he wrote in 1795. He gathered up his collection of petticoats and flung them over to his sister. “‘Sis may have these.’ Being twins, we had always been alike, till then; but from that time forward, I was the man-child and she—poor thing! only ‘Sissy,’ and forced to wear petticoats.” Today, almost all Western children start wearing pants of some sort at an early age, but for centuries a little boy’s first donning of trousers was momentous, worthy of celebration.

This meant a “breeching” ceremony or party. The tradition seems to have started in the United Kingdom sometime in the middle of the 16th century, and then made its way across the Atlantic with early European migrants. It apparently petered out in the early 20th century, perhaps in part because changes in laundry technology made washing soiled pants—after inevitable childhood accidents—a bit easier.

For hundreds of years, pants were thought to have transformative qualities. They turned a little boy from a genderless child, stymied from tree-climbing or other rambunctious activities by long skirts, into a boy ready to enter the rugged world of men. Before that, all small children wore long dresses that extended beyond their feet, like modern Christening robes, before graduating to shorter dresses. Among poorer children, these were totally androgynous garments that could be passed from one sibling to the next. Richer families, though, could afford to differentiate between male and female garments through color or trimmings.

But breeches were a ticket to the wider world, writes Anne S. Lombard in Making Manhood: Growing Up Male in Colonial New England. “Breeches allowed a boy to travel: to run, to climb onto wagons and over fences, and to ride horses. His sisters remained confined in dresses, which inhibited their movements and kept them closer to the house.” In Laurence Sterne’s rambling opus The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Tristram’s breeching opens a new chapter in his education: “‘Tis high time,” his father says, “to take this young creature out of these women’s hands, and put him into those of a private governor.” This begins with his breeching.

With the power of pants came an understanding of manly responsibility, writes Jennifer Jordan in an essay on 17th-century masculinity. “The breeching ceremony stands out as one of the most significant milestones in a boy’s journey to acquiring manhood.” This seems to have been understood by even very little boys. Samuel Coleridge, the English poet and philosopher, described his five-year-old son Hartley being breeched in an 1801 letter. “He did not roll and tumble over and over in his old joyous way,” he wrote. “No! It was an eager & solemn gladness, as if he felt it to be an awful area in his Life.” These parties were usually held over a weekend at home, with relatives invited to stay. The pockets of Hartley’s breeches jingled with “a load of money,” Coleridge wrote, likely gifted to this fledgling man by visiting family members.

Depending on their individual or family circumstances, breeching boys may have been anywhere between four and eight. An 1899 poem by Etta G. Salsbury (taken from the rather slushy collection Our Little Tot’s First Speaker) tells the story of four-year-old Willie, so grown-up and boisterous that his mother brought forward his breeching:

You may be sure that I was glad;

I marched right up and kissed her,

Then gave my bibs and petticoats,

And all, to baby sister.…

I never whine, now I’m so fine,

And don’t get into messes;

For mamma says, if I am bad,

She’ll put me back in dresses!

Often, the decision was a parental compromise. While fathers might have looked forward to playing more active roles in their sons’ lives, mothers sometimes dreaded the loss of their small boys. “Some mothers might try to delay the event, especially if there were no other infants or toddlers in the nursery,” writes historian Kathryn K. Kane on Regency Redingote, a blog about English history. Smaller, sicklier boys might also have their breeching postponed. As soon as they were breeched, their mothers began to spend less time with them. “[Their fathers] might teach them to ride, to hunt, or other gentlemanly sports and activities,” she writes. “Though he did not leave home straight away, a boy who had been breeched had effectively left the domestic sphere of women.”

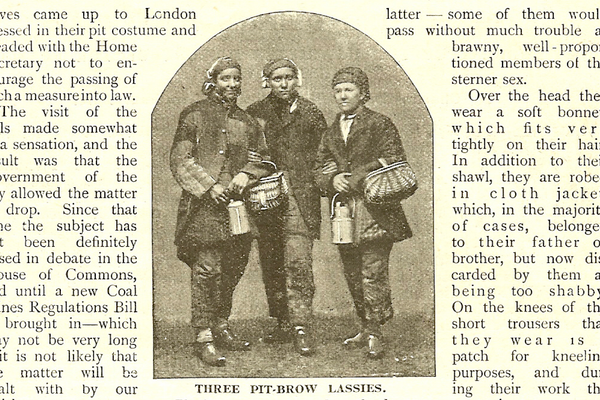

Class, too, had a part to play in when, and how, a boy was breeched. Poorer families were unlikely to commission a new suit from a tailor, and instead might give a child his older brother’s or cousin’s hand-me-downs. A party, if it happened at all, would be much more limited in scope. Often, a breeching at the age of around seven could be an introduction to a life of manual labor.

By contrast, wealthier families’ breeching parties might be lavish affairs, in which the child might even be given a small toy sword. Kane describes how a small boy would change into his new suit and accessories, sometimes helped into them by the tailor or the boy’s father’s valet. “When all was in readiness, family and friends would gather in the room, along with the little boy, in his gown and petticoats. By the Regency, another guest would be present, the local barber,” Kane writes. A little boy would receive his first haircut and emerge a freshly minted young gentlemen, before doing the rounds of the room and receiving a small amount of money from each guest. “There are no records which tell us what happened to this money, though it seems unlikely that such young boys were allowed to keep it.”

But not everyone saw breeching as a positive step. In the 1797 book On Clothing, author and printer George Nicholson worried that pants made urination a needlessly unpleasant experience, and encouraged masturbation through overfamiliarity with one’s genitals. “During the first and second year, the boy can neither button nor unbutton his breeches, and he is continually in a sad condition,” he wrote. More than that, he felt that the restriction on their crotches might similarly bind their nascent brains. “In his breeches, [a boy is] pent up and shackled, and by way of compensation, his mind is stuffed with opinion and folly,” he wrote.

There’s no evidence that a healthy breeze around one’s privates stimulates the intellect, but one of Nicholson’s other concerns, that breeches might have an impact on the future fertility of these young men, may not have been so far off the mark. Recent scientific studies have suggested that tight pants can damage sperm more than smoking or alcohol. Perhaps today’s advances in elastic, zippers, and parachute pants would have eased his mind.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook