Australian Wildfires Uncovered Hidden Sections of a Huge, Ancient Aquaculture System

The Gunditjmara have been building an eel-farming system at the Budj Bim Cultural Landscape for more than 6,000 years.

In Victoria, Australia, an ancient labyrinth of waterways snakes across a once-volcanic landscape. This is the Budj Bim Cultural Landscape, a vast aquacultural system the Gunditjmara Aboriginal people, who still call this country home, began constructing 6,600 years ago. Parts of the system are still in use today.

Ask locals about Budj Bim, and you’ll invariably be directed to Uncle Denis Rose. A Gunditjmara elder, Rose, who has lived here most of his life, cares for the complex as Project Manager of the Budj Bim Sustainable Development Project. His knowledge of this country and its history has earned him the honorific “Uncle,” a term of respect for Aboriginal elders. Bring up the title, however, and he’ll demur. “I don’t refer to myself as that, no,” Rose says. “I’m in a little bit of denial about my age.”

Recently, Rose’s expertise has been in even greater demand. Since December 2019, massive wildfires have devastated Australia, killing dozens of humans and an estimated billion other animals. But in Gunditjmara country, the wildfires have left an unexpected gift. They’ve uncovered stunning and previously unknown sections of the 24,500-acre complex, including an 82-foot channel that was obscured by thick brush. The find reinforces our understanding of the vast scale and sophistication of the system, which UNESCO designated a World Heritage Site in 2019 after decades of Gunditjmara struggle to reclaim their land and culture.

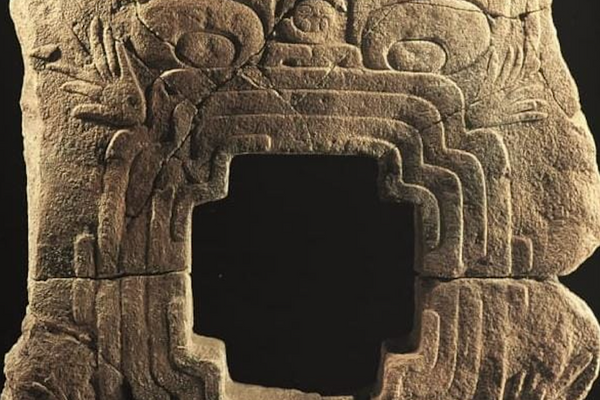

The aquaculture system was born in a fiery act of creation. Around 30,000 years ago, the Budj Bim volcano began coating the country in streams of lava. Gunditjmara ancestors understood the explosions as the work of an Ancestral Being they called Budj Bim, who transformed himself into the landscape through lava flows. Eventually, volcanic activity slowed, and the hot basalt rock cooled into a foundation for vibrant wetlands, including present-day Lake Condah.

Around 6,600 years ago, Gundijtmara began transforming the landscape. They used heat to forge channels from the basalt, structuring the wetlands into a perfect habitat for short-finned eels called kooyang. Year-round eel populations and an elaborate system of traps allowed the Gunditjmara to settle and build stone houses. In all, Gunditjmara people constructed around 70 individual aquaculture systems, including channels up to 1,000 feet long.

The Gunditjmara managed the surrounding country through cultural burning, a system of low-intensity, intentional fires that Aboriginal Australians across the continent have used to regulate their ecosystems for millennia. Similar to Native American uses of flame in the American West, these periodic burns create ideal habitats for the prey that humans like to hunt, and eliminate the dry brush that fuels more destructive, lightning-sparked fires

Budj Bim remained a center of Gunditjmara life for thousands of years. Then came Europeans. The British first spotted Australia in 1770, but they didn’t reach Budj Bim until 1841, when government official George Augustus Robinson arrived in southwest Victoria on an exploratory expedition. Artwork from that time reveal a brushless landscape shaped by cultural burning. Descriptions reveal European racism. Robinson described the aquaculture system as “resembling the work of civilized man,” but noted, with evident shock, that “on inspection I found [it] to be the work of the Aboriginal natives.”

Robinson’s find was, to say the least, inconvenient for the British, who had based their claim over Australia on the doctrine of terra nullis. Ancient Romans had invented the concept, which means “land belonging to nobody,” to justify their own imperial takeover of lands they said weren’t in productive use. When the British first reached Australia, they claimed the continent was “a tract of territory practically unoccupied, without settled inhabitants or settled law.” Faced with the inconvenient fact of Aboriginal ingenuity, the British ignored it and stole their land.

British and, later, Australian officials forbade cultural burning and drained many of the swamplands around Budj Bim. Settler violence and European diseases devastated Gunitjmara populations. While Gunditjmara people fought back, they were eventually pushed onto a number of church missions in the area, where colonizers undertook a genocidal project of cultural erasure.

“We were actively discouraged from our traditional practices,” Rose says. While much of the area around Budj Bim was made a national park in 1960, the lack of Gunditjmara control of their land caused much of the aquacultural system to fall into disuse. At the same time, the lack of cultural burning led to overgrowth that hid sections which have only now been uncovered.

But Gunditjmara people managed to sustain their culture, thanks to the resilience of community elders like the late Aunty Connie Hart. Hart grew up on a mission in the 1930s, where she’d watch elders weave baskets of dry grass. Although she was forbidden from learning the practice, she watched and memorized their technique. When Hart returned to Gunditjmara country after a few decades in Melbourne, she started teaching traditional basket weaving. For Rose, the anecdote represents the resilience of a people determined to hold onto their values despite almost two centuries of colonial violence. “While there was a concerted effort not to pass those things on, they still did.”

In the past several decades, the Gunditjmara have reclaimed their land and aquaculture. Beginning in the 1980s, a series of court cases recognized the legitimacy of Aboriginal claims, and in 2007, the Australian government fully recognized Gunditjmara land rights. Today, Gunditjmara people have native title, or traditional ownership rights, over 540 square miles of traditional land, and co-manage Budj Bim National Park with the Australian Government. This includes the sprawling Budj Bim Cultural Landscape, which is managed by the Gunditj Mirring and Winda-Mara Aboriginal Corporations. Gunditjmara rangers are now focused on rehabilitating the damaged wetlands and reinstating traditional fishing practices by teaching young people to catch eels with woven grass baskets.

While the recent fires have devastated some communities, rangers say they’ve helped renew the Budj Bim Cultural Landscape. Here, the blaze was relatively slow-moving, low, and “cool,” largely sparing treetops while clearing underbrush. The fires revealed swathes of the aquaculture system that even Rose, who estimates he’d visited the areas around these sites at least 20 times a year, never noticed.

“It’s been absolutely fantastic,” says Leigh Boyer, a Gunditjmara ranger with the Winda-Marra Aboriginal Corporation, who coordinates tours of Budj Bim. Archaeologists and rangers are planning a survey of the newly uncovered sites, including an assessment of any potential burn damage. The assessment may lead archaeologists to adjust their assessment of ancient Gunditjmaran population size, which has been historically underestimated.

The new find could also be good news for tourism. Gundijmara rangers are eager to welcome visitors—within limits. “The protection of our cultural heritage is our main priority,” says Boyer. He believes tourism can be both profitable and sustainable, and hopes visitors gain an appreciation for Gunditjmara heritage while economically empowering the community. Visitors can view the site, including eel traps and ancient stone houses, through ranger-led tours. They are not, however, permitted access to the oldest part of the aquaculture system. “It’s too precious,” Boyer says.

Going forward, both Rose and Boyer say rangers’ first goal is to ensure the health of their country. They’re experimenting with reinstating cultural burning, which requires particular care in a rocky landscape. “It’s all a bit of a learning process,” says Rose. But for Gunditjmara rangers, these efforts are more than worth it.

“There’s something about this place that keeps on drawing me back,” says Boyer, who has lived on Gunditjmara country for most of his life. The country’s history is the Gunditjmara’s history; its life extends deeper in time and meaning than even a UNESCO World Heritage designation can capture. Rose says it simply: “I started my journey here, and I’ll finish it here.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook