There Maybe Could Possibly Be a Treasure Buried Under Portland, Oregon

At least according to a hand-drawn map of mysterious origin.

The archives of the Oregon Historical Society Research Library in Portland house many treasures—but only one honest-to-goodness treasure map.

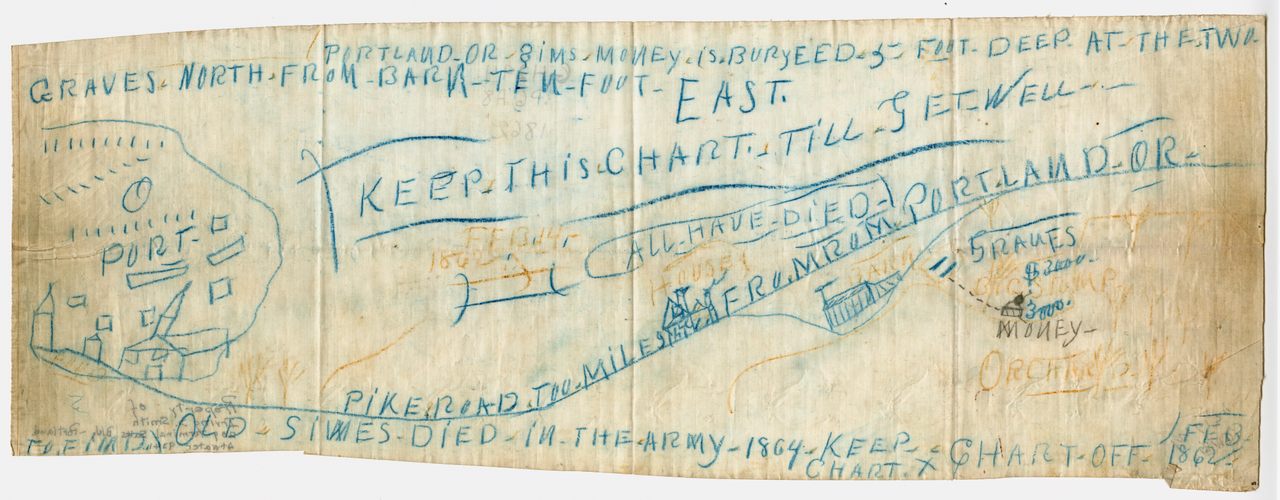

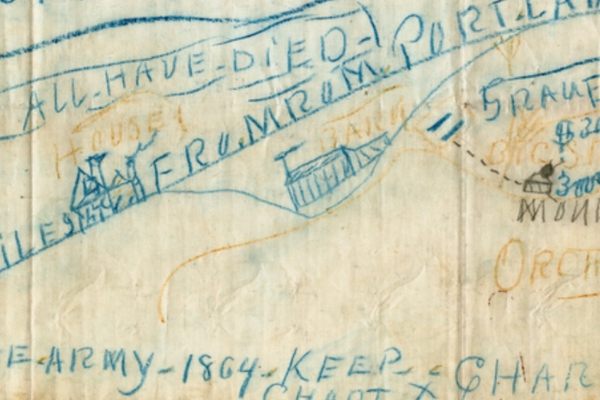

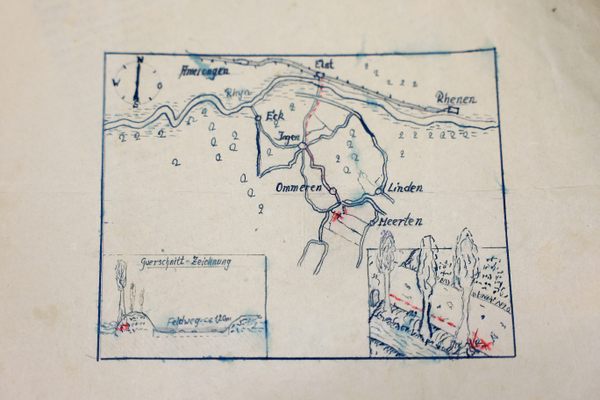

“It is an odd thing,” says research services manager Scott Daniels of manuscript number 2039, a scrap of creased and stained tracing cloth kept in the library’s climate-controlled vault. Unfolded, the document is 6 inches tall and 18 inches wide, covered from edge to edge on one side with long strings of blunt capital letters written in blue pencil, and a crude map sketched in blue and yellow. On the far left, there’s a port with a building topped by a tall spire on its shore. And on the right, there is a barn and two slashes that seem to be gravestones. In black ink, someone has written “MONEY”—highlighting two separate caches of $3,000 each. In February 1862, when the map seems to indicate the treasure was buried, $6,000 would have been a fortune, several years wages for the average worker.

“There’s just enough on there that people think they possibly recognize some of the landmarks,” Daniels says, 160 years later after the map was supposedly created, “but most of it is still a mystery.

In 1862, Portland was the largest city in the new state of Oregon, with a population of almost 3,000, a growing port, and a daily newspaper, the Oregonian, which reported nothing of note on February 14 of that year. That’s when—if the treasure map is to be believed—someone buried “SIMS.MONEY” five feet deep alongside two graves. To rediscover the loot, the map suggests, one should follow “PIKE.ROAD.TOO.MILES.FRO.MROM.PORT.LAND.OR.” There, one would find a barn. The graves lay north and east of the structure, near an old stump and an orchard.

Perhaps it was Sims himself who hid his fortune, but the map notes that Sims (also referred to as Simes) died in the army in 1864, in the midst of the Civil War. So, it seems that someone else knew his secret. Another annotation hints at the fate of this confidant—or perhaps it offers a warning: ALL.HAVE.DIED.

No one is certain about the authenticity of the map or who kept it through the 19th century; its existence did not become public until 1940, when the Oregon Historical Quarterly published a short note about the document. The map had been discovered a few years earlier after the death of a Seattle judge named Everett Smith. His son, Irving, had found it among his father’s papers. At the time, Irving told the Oregon Historical Quarterly that his father had never mentioned the map and left no written explanation, but several decades later, Irving told the Oregonian that he learned the map had previously belonged to an indigent man whose estate had been settled in Judge Smith’s court. Irving also admitted that he had hunted unsuccessfully for the treasure before revealing the map’s existence.

The Oregonian had tracked down Irving Smith at his home in Oklahoma City in 1966 because treasure hunters were on the prowl in Portland. Renewed interest in the century-old treasure may have been sparked by the 1957 publication of the book Lost Mines and Treasures of the Pacific Northwest, a collection of local lore by Ruby El Hult. Hult recounted the story told by the Oregon Historical Quarterly and despaired over the scant information and seeming dead ends the map provided. There was no evidence of a man by the name of Sims or Simes with Portland connections who died in the Civil War, and there was no record of a Pike Road in Portland. She also wondered if the misspellings on the map were not mistakes but coded messages, particularly the seemingly nonsense phrase “fromrom.” Ultimately, she concluded, “on this one it would be hard to know how to proceed, unless by good chance someone unearthed more information.”

That didn’t deter the fortune seekers—nor did the unexplained disappearance of the map itself. In 1966, Hult wrote to the Oregon Historical Society looking for the original document. The response was disappointing: “Yes, the subject of the Portland treasure chart has come up before. As far as I know or we could ever find, OHS doesn’t have that chart.” The curious worked, instead, from Hult’s secondhand description to reach starkly different conclusions.

Some believed “Pike Road” to be an old nickname for Plank Road (now known as Canyon Road), an early thoroughfare paved with wood, while others thought “pike” could refer to any main road, as in a turnpike. One treasure hunter, Ruth Burgess, was certain it was a mountain road; in British English “pike“ refers to a mountain or hill with a peaked summit. She, along with her husband and four children, followed Belmont Street east toward Mount Tabor, starting from the approximate location where a Roman Catholic church had stood in the 1860s. (Her interpretation of “fromrom” was “from Roman.”)

Many of these adventures ended in the same disappointment: Two miles down the road they had chosen, the treasure hunters found a completely different Portland than the one that had existed in the 1860s. One woman who was convinced the key lay in rotating the map 90 degrees counterclockwise ended up at a construction site where backhoes were digging a driveway for the city’s new zoo. A man whose quest for the $6,000 was derailed by the Vietnam War returned home to find the city was planning a freeway where he believed the money to be buried. And Irving Smith thought the treasure was near the Montgomery Ward building—land that had also previously been used to host the massive Lewis and Clark Exposition.

Ruth Burgess and her family, however, ended up near a cemetery—with a lot of guesswork, they even settled on a pair of graves. But they did not dig. “I kind of like my freedom,” Burgess said, “and being they rest on city owned property, I imagine they kind of frown on grave robbing.”

Today, the Oregon Historical Society doesn’t see many treasure hunters. Scott Daniels estimates he’s met just 10 or 12 in the 15 years he’s worked at the research library. Those who do come ask to see the original map. That, at least, has been found. Daniels speculates that it was never missing, exactly, just packed away for the Society’s 1966 move to its current downtown location.

Daniels is not sure if there’s $6,000 buried somewhere in Portland, but the map has proven to be a treasure to the archive. He loves to show it off to middle and high school students who might think that the history of Portland is boring. “They tend to be very fascinated by this map,” he says. “I use it to illustrate how archival stuff can be fun.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook