Canada’s Ice Roads Are Melting Too Soon

Climate change is fraying these seasonal lifelines, causing hardships for the remote towns that rely on them.

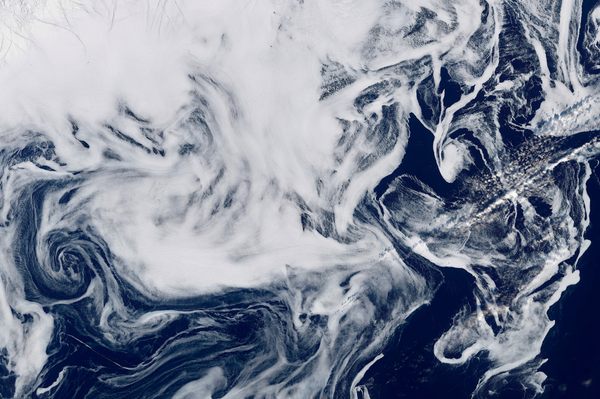

It’s March in Canada’s Northwest Territories, almost 200 miles above the Arctic Circle, and the Mackenzie River Delta is frozen solid. Seen from above, its marbled surface is laced with cracks, criss-crossing one another and extending deep below the top layer of ice.

It’s beautiful to look at, especially in the clear arctic light of a winter midday. But it’s difficult to reconcile something so fragile-looking with the 54 vehicles that drive over it on a typical March day. As Noel Cockney of the Inuit-owned Tundra North Tours tells a small group of travelers bundled into his van, this isn’t just a frozen river. This is the Inuvik-Aklavik Ice Road.

The 73-mile-long seasonal highway that connects the town of Inuvik, the region’s administrative center, to the remote community of Aklavik later takes the group past an immobilized barge, two stories high, encased in ice when the river froze around it. Come springtime the barge will be free again—and Aklavik will once more be inaccessible by land.

Ice roads in northern Canada appear each winter as if by magic, then melt away in spring. When lakes and rivers freeze, they offer temporary access to places that, the rest of the year, are reachable only by barge or air. A network of ice roads, built and maintained by the territory’s department of transportation, cross the Northwest Territories, linking 10 towns.

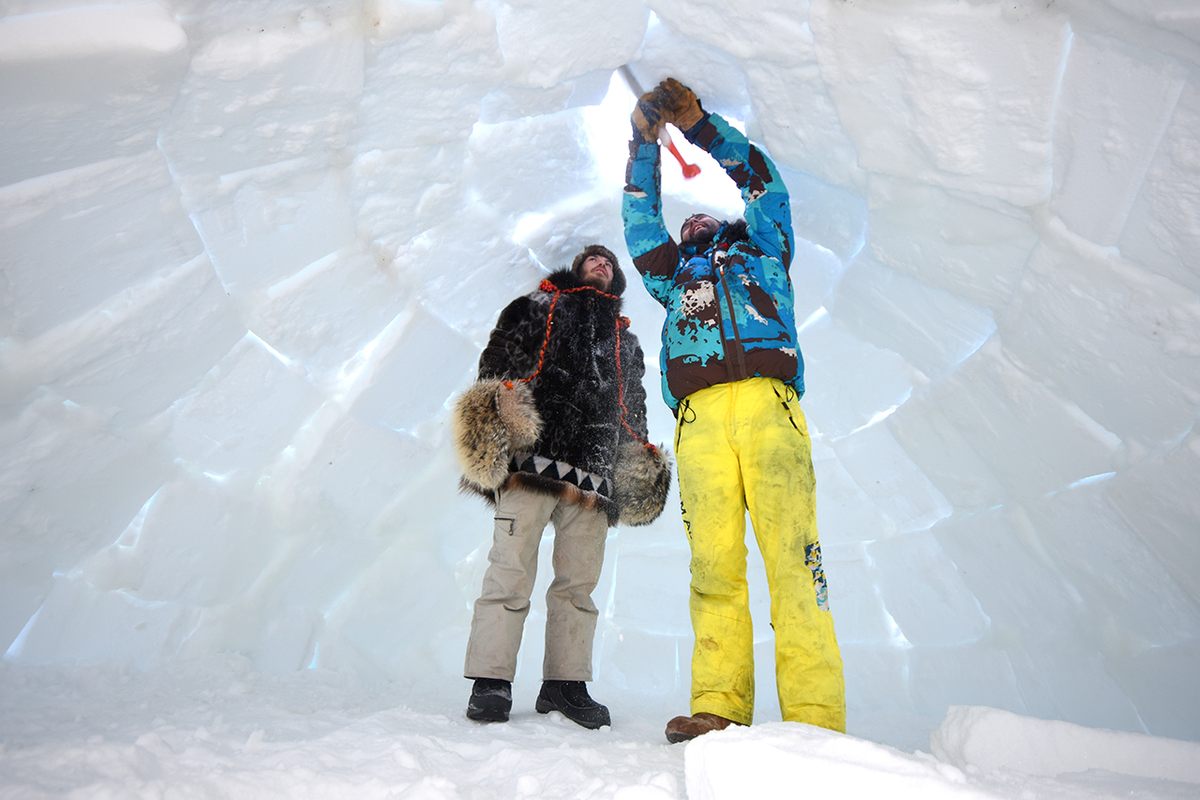

But there is, of course, no magic. Only a complex process that involves radars, to check the thickness of the ice; snowcats, to remove the insulating snow cover; and heavier snow plows, to build up the ice and finish the job.

The Department of Infrastructure has highway-maintenance staff across the NWT who conduct daily inspections during the ice-road season. To ensure that the road is safe to travel on, they use ground-penetrating sensors—tethered to equipment such as snowmobiles or Argos (amphibious vehicles)—to monitor the condition of the ice.

This part of Canada, however, is warming at a rate four to five times faster than global averages, according to a recent report by the Government of the Northwest Territories—and that’s causing big problems for the people who rely on these ephemeral roads.

Ice roads are a seasonal lifeline for some of the most isolated settlements in the North. The hamlet of Aklavik is one such community. Home to about 600 people—mostly Gwich’in and Inuvialuit (western Canadian Inuit)—the area was traditionally a trading place for nomadic indigenous people. In the early 20th century, when the Hudson’s Bay Company established a fur trading post here, Aklavik became a permanent settlement and the region’s administrative center.

In the 1950s, however, periodic flooding of the Peel Channel and subsequent erosion led the government to establish Inuvik—built on higher, drier ground some 60 miles to the east—as the region’s new center.

But instead of abandoning Aklavik, as the majority of white settlers did, many indigenous families decided to stay put. They were used to a traditional hunting and trapping lifestyle, says Cockney—familiar with the land, and sure that they could find the food they needed.

Aklavik’s resilience is expressed via its coat of arms, which bears the legend “Never Say Die.” Still, it has the appearance of a place ever on the edge. Houses are raised off the ground on stilts, so that their warmth doesn’t melt the permafrost on which they’re built. Next to a small graveyard, where crosses are nearly submerged under deep snow, a rough-hewn sign marks the grave of Albert Johnson—“the Mad Trapper” who was killed at the culmination of Canada’s largest-ever manhunt.

Tundra North Tours’ mission is to provide visitors “with an authentic experience of the unique atmosphere and culture of our home in Canada’s North.” Part of that experience entails meeting with Aklavik elders, traditional repositories of community knowledge.

Danny and Annie Gordon are two of them. In their cozy one-level home, photographs of family members and Inuit sealskin hangings cover the powder-blue walls. Cheerfully—Annie’s whole face lights up when she smiles—and patiently, the pair regale visitors with stories of their lives in Aklavik.

In 1947, when he was just nine years old, Danny walked with his family all the way from Utqiagvik (then named Barrow), Alaska, to Aklavik, where Annie has lived her whole life. For their first two years there, his family lived in a tent before moving into a house. He and Annie married in 1956.

Today, Danny continues subsistence hunting and trapping—muskrat and pine marten pelts cover their living-room floor. He talks warmly of heading out onto the land with his children and grandchildren, keeping alive the tradition of whole families going trapping and hunting together. Smiling, he recalls taking out their 17-year-old great-grandson, whom he describes as “smart on the land. You teach him once, he doesn’t forget it.”

But the tourism made possible by ice roads presents other opportunities. Annie runs a small craft shop, called Okevik, from their home, selling her own handmade items like beaded slippers and mukluk boots. Danny also crafts tools for sale: snow goggles made from carved wood, hunting knives with caribou antler handles, and ulus (half-moon-shaped knives used for cutting food and cleaning pelts).

For year-round residents like the Gordons, the ice road is crucial to accessing Aklavik in winter. But like much else these days, it’s being affected and afflicted by climate change.

“I’m 30 years old, and even I have seen a difference,” says Cockney, who hails from the Inuvialuit hamlet of Tuktoyaktuk, about a hundred miles north. Until recently, his hometown was accessible only by ice road. Now an all-weather road connects Inuvik to Tuktoyaktuk, which sits on the edge of the Arctic Ocean.

But a permanent road can’t entirely shield the hamlet from the impacts of climate change: Accelerating coastal erosion is threatening homes and putting the entire community at risk

The rapid warming of Canada’s North is due to a number of factors, including loss of snow and sea ice, which increases absorption of solar radiation and causes more surface warming than in other regions. Thawing permafrost and coastal erosion are big problems too.

“The winters have shortened by around one month in total,” says Cockney. That means the region’s crucial ice roads are closing about two weeks earlier each spring than they used to, and opening about two weeks later.

As ice roads around the North melt earlier than ever before, the communities that depend on them are facing increased isolation and higher costs for basic goods, which now have to be flown or shipped in. In Aklavik a gallon of milk costs $15 (roughly $18 in U.S. dollars), while a gallon of gas runs $8 ($10).

Danny Gordon says that some adjustments to a traditional lifestyle have their benefits. He long ago replaced his dog team with a snowmobile, for instance, so he doesn’t have to attend to animals every day. Now, he jokes, ”I can turn them on and off with a key.”

Aklavik residents have to stock up on goods and visit family and friends during the final weeks of the ice-road season, which typically runs from December through the end of April. If a road closes abruptly, or earlier than residents had been planning for, it can cause prices for everyday goods to spike (incomes here are already lower than average for the NWT).

“A lot of food is brought along the ice road,” says local hunter J.D. Storr. A shorter ice-road season also means higher gas prices, which have a particularly serious impact on those who hunt for food. “It’s getting harder for people to get out onto the land,” Storr says.

Some support comes from the Aklavik Hunters and Trappers Committee, which gets funding from the Northwest Territories Government for Community Harvesters. The committee assists locals with gas “to help them harvest for their families.”

As ice roads become less reliable, permanent roads seem increasingly necessary. Six-hundred miles to the south, work is progressing to replace the ice road that serves the Tłįchǫ Dene community of Whatı̀ with a 58-mile all-weather road. Government spokesman Greg Hanna says that building the Mackenzie Valley Highway and the Slave Geological Province all-season highway are the transportation department’s next priorities.

But replacing winter roads with year-round ones is an expensive and time-consuming solution. The new Inuvik-Tuktoyaktuk Highway, for instance, cost $225 million and took more than three years to complete.

After Cockney’s tour last March, unseasonably warm weather destroyed Tundra North Tours’ igloo village, just off the Inuvik-Aklavik Ice Road, where guests used to spend the night. It also affected the region’s popular spring festival, the Muskrat Jamboree. Attendees were advised not to park their vehicles on the compromised road.

A small inconvenience, perhaps. But for residents for whom the ground under their feet is increasingly unstable, it’s another worrying symptom of what’s in store for the North as the world warms.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook