The Eccentric Adventures of Captain Davis, Sea-Desert Dweller

He lived on Mullet Island in the Salton Sea, ran a desert dancehall called Hell’s Kitchen, and obsessively retraced the steps of the Donner Party.

The Salton Sea, southeast California’s vast inland lake with a tumultuous environmental history and a surface nearly 240 feet below the ocean, is a mecca for obsessives. A former tourist destination and resort area, the lake is now beset by the smell of thousands of dead fish and surrounded by a cluster of ghost towns, the kinds of places where you can take up space or disappear. The salty sea, now the object of many attempts at renewal and revitalization, still draws in folks who are looking for something in its bleak vastness (anarchy, artmaking, something like freedom)—and those who are running from something else.

At the end of the 19th century, Captain Charles E. Davis was both. Captain Davis—a moniker he earned at 18 in an Atlantic fishing fleet, and never gave up for the remainder of his life—was no stranger to failures, or to abandoned projects. He tried and failed to pan for gold in Alaska, was an apparently unsuccessful miner in the Klondike, and explored the Caribbean, Siberia, and the Amazon before “retiring” in the Salton Sea.

Born in Massachusetts to a wealthy family, Davis abandoned them for the sea, then the sea for the desert. He found the best (worst?) of both in 1898 in what would become the Salton Sea seven years later. He lost everything to a harrowing flood in Galveston, Texas, in 1900, only to return to his safe haven in California and witness the unholy birth of his future home when the Colorado River flooded the Salton Sink.

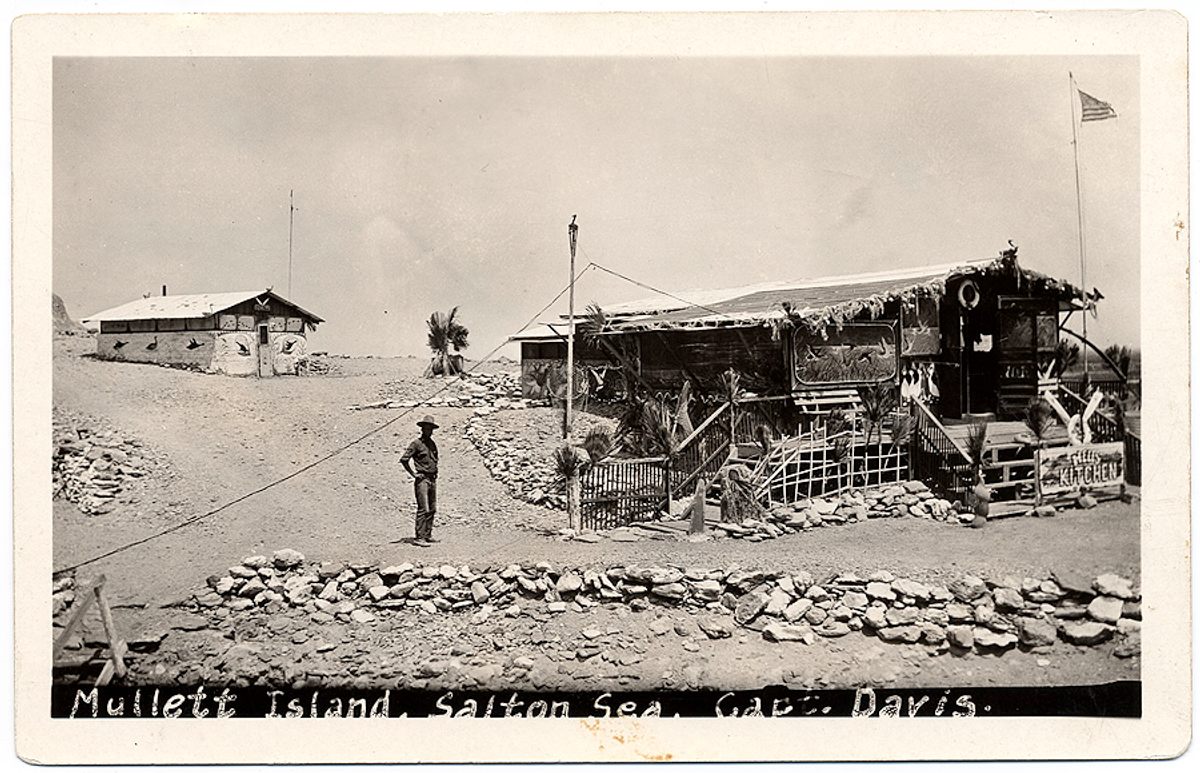

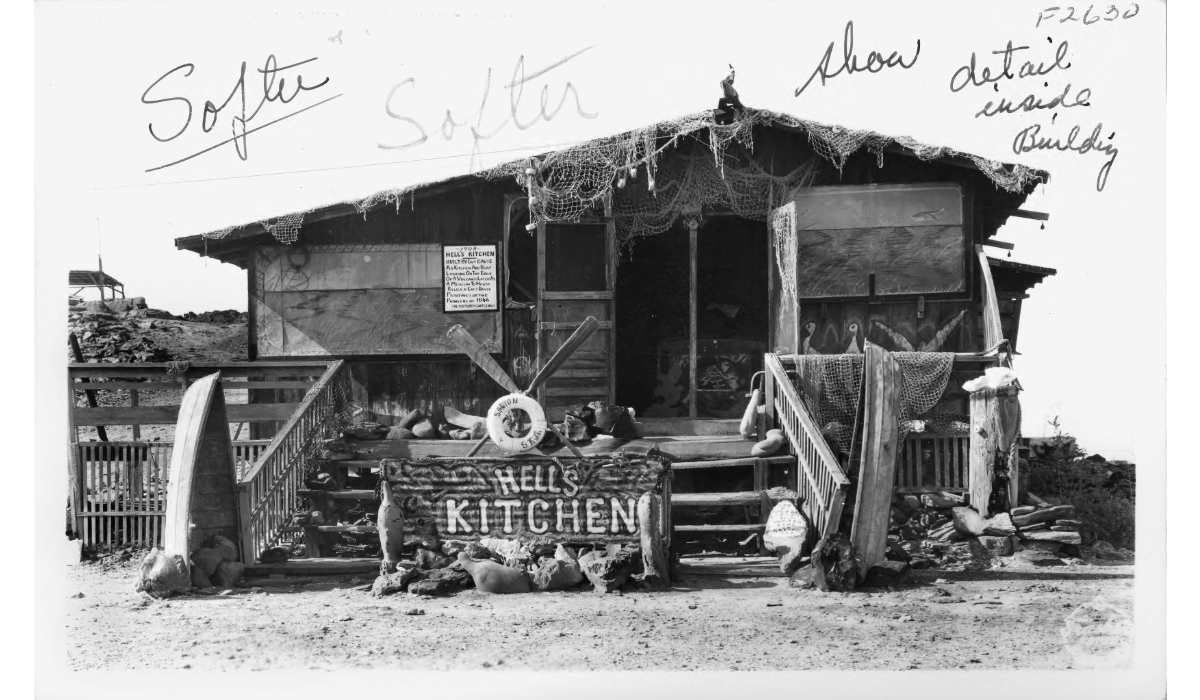

There, Davis developed and inhabited Mullet Island, on top of an inactive volcanic butte and among what Salton Sea historian Pat Laflin calls “an inferno of hissing geysers and boiling mud pots.” It was befitting of Davis’ character to live atop a dormant volcano, and that is said to have been one of the site’s major draws for him. The island was named for the alfalfa-fed mullet that Davis raised, which later became famous throughout California. It also became the site of Davis’ passion project, Hell’s Kitchen, a combination boat landing/restaurant/dancehall where boaters and fishers often stopped for good food and a good time. Davis built it alone, along with his own cabin.

In the 1920s, Hell’s Kitchen’s heyday, motorcyclists and adventurers frequently wrote about Hell’s Kitchen’s oddball charms. Describing Mullet Island as “the headquarters of the Salton Sea fishing industry,” one 1922 periodical noted that Hell’s Kitchen was so named because it was “on top of a volcano and may blow off into space any minute.” (The same could be said, perhaps, of Davis.)

A 1920 edition of Popular Mechanics added that area fishermen, seeking to catch the lake’s signature mullet to be sold in San Francisco restaurants, had to sludge through the muddy waters of the Salton Sea underneath canopies, as temperatures regularly climbed to over 125 degrees. But Davis seemed at home there in this cursed corner of the world, setting up shop for over 25 years and serving as the unofficial head of the local fishing industry.

Davis brought his signature spunk, strangeness, and aplomb to all his endeavors at Mullet Island. At Hell’s Kitchen, Kim Stringfellow explains in her book and installation project, Greetings from Salton Sea, Davis was performer, cook, and host alike, holding dances, serving up dinners, and singing sea shanties for customers. He was, by all accounts, a rugged sort, aided in his work by predictably named laborers like “Shorty” Bell and “Slim” Clifford, and seemingly not bothered by the uninhabitable heat of his makeshift home. He fought in local political efforts, primarily for environmental conservation and historic preservation.

Most of all, Davis kept on doing what he did best: failing, and failing big (better than most succeed). He tried to convert a fishing boat into a showboat, says Randy Brown, who recently documented his experience as (most likely) the first person to walk around the shoreline of the Salton Sea. “He brought a barge up from San Pedro that sank as soon as he put it in the water,” Brown explains. He also imported six sea lions that promptly died in the Salton Sea’s toxic waters and became a source of local contention among locals who accused the sea lions of pig-stealing.

Later, the island’s nearby mud pots served as raw materials for another burgeoning compulsion. Davis developed a fascination with the infamous Donner party and their ill-fated venture that reportedly ended in cannibalism—perhaps, as Diane Bush surmises in Thaw: A Memoir, her hybrid memoir about Davis’ eccentric history, inspired by his own many explorations gone awry.

Davis used homemade oil paints—hematite concretions (“Indian paint pots”) dissolved in fish oil—to create hundreds of paintings based on the Donner Party, which he kept at his headquarters on Mullet Island. This “art gallery,” as Bush describes it, “explores the terrain of loss.” Though reporters speculated that he was enamored with the pioneer spirit, it’s likely, too, Bush suggests, that he was exploring the art of where things go wrong—one in which he was well versed.

Still, paintings weren’t enough: As usual, Davis had to see for himself. Armed only with newspaper clippings and a truly absurd amount of research, he is likely the first person to have traced the Donner party’s 1846-1847 travels from Independence, Missouri, to Sacramento, California (over 2,000 miles). He based his destinations on his own investigations and artifacts he’d found, and added 1,027 photographs and a number of relics to the growing Donner party collection.

Local media outlets wrote about Davis with a mixture of awe, bemusement, and perhaps a bit of fear: Breathless descriptions alternately described him as a traveling eccentric, a pioneer, and an amateur historian. In 1927, a reporter at the Oakland Tribune wrote that history buffs in the Sierras had developed “a renewed interest in the Donner party tragedy as a result of Davis’ explorations” and concluded that, after his trek’s end, Davis would “rest awhile and then break into public notice again with some crusade that only a man who ‘sees God in the clouds and hears him in the wind’ would think of undertaking.” Davis donated the photographs he took and the artifacts he found to Harry C. Peterson at Sutter’s Fort, where they are now housed in the Charles E. Davis Overland Trail Project Collection.

Today, Mullet Island is no longer an island, but a peninsula, experts say. The last geysers in Mullett Island’s hot springs disappeared in the mid-20th century. The birds, too, have left, says Brown: “The island was populated by tens of thousands of cormorants,” he explains, “but now that predators can walk up to the island and eat their eggs from the nests, the birds have all left. But you will still find thousands of their nests all over the rocks on the island.” The mud pots are only accessible by boat and by foot, and the foundation of Davis’ hand-built dwelling still stands.

Davis, like the Salton Sea itself, appears to have been haunted, eerily beset by the ghosts of stories past. His persona is so offbeat that it almost seems to have been constructed, fashioned self-consciously as a figure who would be written about in newspapers and serve as a model for future explorers with passions and obsessions of their own. He officially acquired the deed to the 160 acres that made up Mullet Island in 1926, and in 1928, he essentially disappeared, only returning to Massachusetts shortly before his 1933 death.

Diane Bush notes that in photographs, Davis rarely looked straight at the camera and was always wearing his signature hat, as if he wanted to be anonymous, unseen—strange, given his propensity for larger-than-life undertakings. Perhaps, like many of the current inhabitants in nearby Slab City and Bombay Beach and many of us who’ve found something to obsess over in the Salton Sea, he needed the whole of the wide expanse of the desert and the sea to unfurl himself.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook