Simulating What Could Happen When the ‘Really Big One’ Hits the Pacific Northwest

When the Cascadia subduction zone slips, the effects will vary based on where and how.

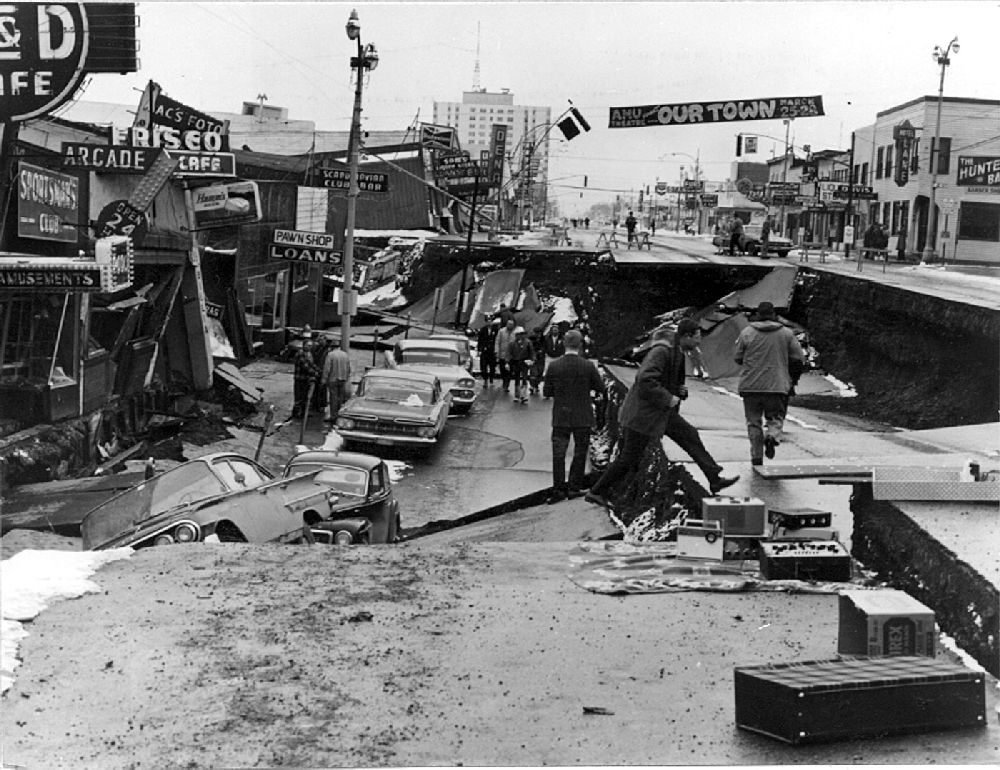

Scientists know that a massive earthquake will one day shake the Pacific Northwest. At some point in the future, pressure building on the Cascadia subduction zone will reach a breaking point, and the Juan de Fuca plate will slide further under the North American plate. It happens roughly every 500 years, and when it does it is going to be big. But earthquake propagation is impossibly complex, so no one knows how much shaking different cities in the region will experience. The last time a subduction zone quake rattled the region, it was January 26, 1700, and all we know about it comes from tree ring data, sediment cores, oral traditions of indigenous peoples living in the area, and records of an “orphan” tsunami in Japan. To understand the inevitable shaking, scientists have produced a new set of simulations of the “Really Big One”.

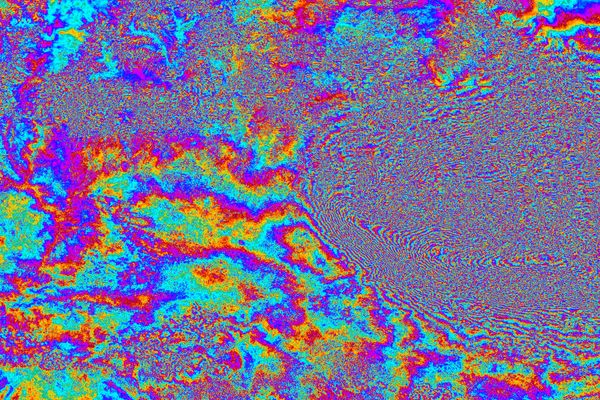

A team of researchers from the University of Washington and the U.S. Geological Survey used supercomputers to simulate 50 different earthquake scenarios along the subduction zone. Pressure isn’t evenly distributed along the fault, and the nature of the quake will depend on whether the entire fault or just a portion of it moves. The location and depth of the epicenter will also affect the intensity of shaking, which is important for places built on sediment that liquifies during a quake. The team’s simulations focused on Seattle, with a variety of different epicenters, depths of fault movements, and “sticky points,” where the Juan de Fuca plate might snag on the North American plate and generate even more shaking.

Worse for Seattle (Courtesy Nasser Marafi/University of Washington/CC BY 2.0) from Atlas Obscura on Vimeo.

Intuitively, one expects that being farther away from the epicenter is better—but that’s not always the case. The simulations show that the Emerald City fares best when the epicenter is right next to it, under Washington’s Olympic Peninsula, which may cause most of the quake’s waves spread out and away from the city. “But when the epicenter is located pretty far offshore,” said team member Erin Wirth in a statement, the waves travel inland, “and all of that strong ground shaking piles up on its way to Seattle, to make the shaking in Seattle much stronger.” The latter simulation can be seen in the video above.

A magnitude-9 earthquake will be devastating for the Pacific Northwest, no matter where it originates. But with a better sense of possible or likely scenarios, geologists may be able help cities and people prepare for what a “Really Big One” really means.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook