Why Europe’s Cave Bears Were—and Weren’t—Made for Hunkering Down

Their big sinuses were both an evolutionary boon and bust.

As we’re all learning these days, not all hibernations are happy ones. Some are punctuated with boredom, bad sleep, and morose, empty food stores. Cave bears could relate. Turns out their long hibernations—combined with their veggie-heavy diets and spacious sinuses—may have been what caused their demise.

Alejandro Pérez-Ramos, a paleobiologist at the University of Malaga in Spain and lead author of a new study published in the journal Science Advances, says that cave bears developed big sinuses to help them hibernate for long periods of time. But evolution giveth and evolution taketh away: In doing so, the bears’ capacity to chew with their front teeth was impaired.

Bears are famously omnivorous animals, known for their spectacular fish-farming on salmon runs and their deft tree-clambering to access acorns, berries, and, of course, honey. But cave bears were different. A species that could grow up to 50 percent larger than today’s grizzly bears, they spent most of their time indoors, sequestered in the many caves of Europe, before going extinct at the height of the last Ice Age, about 25,000 years ago.

A prevailing theory posits that humans seeking shelter in those caves are what threatened the bears’ homesteads and survival. Now, Pérez-Ramos’s team suggests a second culprit: The cave bears’ large sinuses, they say, prevented the animals from acclimating to a frigid world with fewer greens.

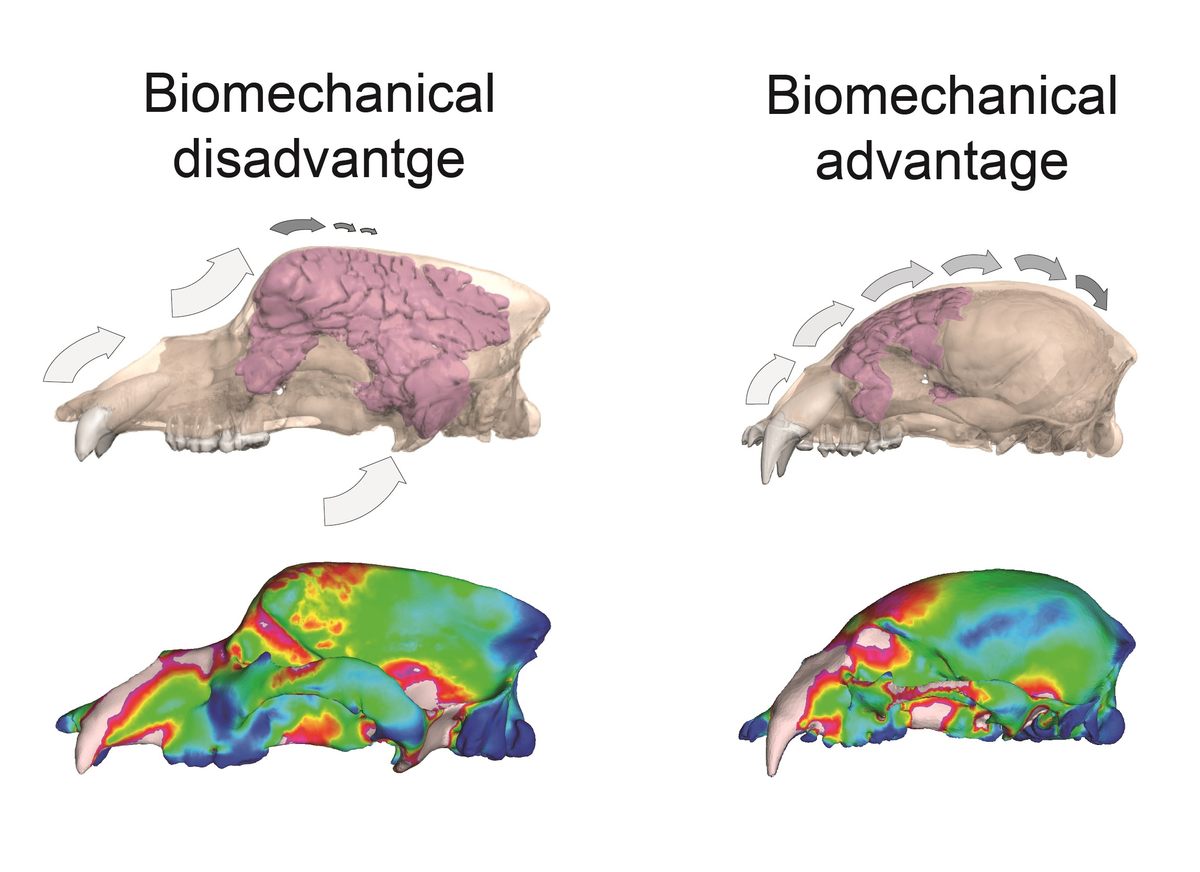

Using 3D computer simulations of different feeding scenarios, the team analyzed how the bites of 12 different bear species distributed strain across their skulls. Cave bears, with their large frontal sinuses—which may have promoted hunkering down to hibernate—held most of their chew power in their molars (good for fibrous foods, as is the case with pandas).

Cave bears are thought to have hibernated for longer periods than their modern relatives, due to those long Ice Age winters. Pérez-Ramos says that while their large sinus area helped make their hibernation efficient, their sparse diet could have led them to run out of fat reserves during their months-long slumber.

When the Ice Age reached its peak chill—a time when temperatures plunged to 10 degrees lower than today’s average—it changed what was on the environmental menu. Vegetation couldn’t grow and fuel the ecosystem’s meat-eschewing habitants. While other predators could hunt down prey and satisfy their protein needs, cave bears were out of luck, their grinders biomechanically opposed to the meaty menu that the ecosystem was offering.

That, and the expansion of humans into Europe’s grottoes, ultimately proved too much for the lumbering cave dwellers.

While few of us can afford to doze for months on end, the fall of the cave bears is a friendly reminder to make sure your pantry is well-stocked—and not just crammed with toilet paper.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook