Cavemen Inherited Their Clubs From 16th Century European Wildmen

A caveman at a German theme park (Photo: Martin Lewison/Flickr)

Like Cupid has a bow, like ninjas have nunchucks, cavemen have clubs.

Back in the 18th century, Voltaire explained that early men had only a few options for defense: “hurling stones and arming themselves with great branches of trees.” In 1897, the father of Ab, one of the first cavemen to be featured in a novel, carried a three-foot length of wood, with a stone lashed to it, and this weapon, described as a “heavy club,” allowed him to easily smash the heads of hyenas. Alley Oop, the comic-strip caveman of the 1930s, had a similar weapon; in the 1960s, Bamm-Bamm arrived in the Flintstones’ fourth season pre-equipped with a giant club; in the 1970s, the very hairy Captain Caveman wielded his with abandon.

And, perhaps most famously, in 2001: A Space Odyssey, it is the discovery of the club–a bone lofted overhead and brought down with force to smash a vulnerable skull–that begins the history of man.

But the historic record for club-wielding hominins is thin, to say the least.

“To arm the hand of primitive man with a club seems perfectly natural to us, but we can find no trace of it in museum cases or in archaeological archives. The club is just not there,” writes Wiktor Stoczkowski, a social anthropologist, in his 2002 book Explaining Human Origins.

The absence of any real evidence for this classic pairing raises the question: From where, exactly, did the caveman get his club?

Possibly, he borrowed it from a character with a much longer history in Europe—the wild man.

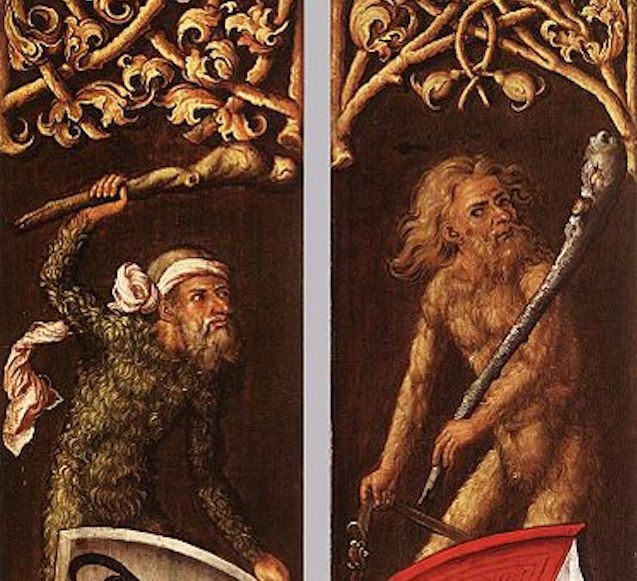

Durer’s wildmen (Image: Albrecht Durer)

The wildman first began thriving in European mythology in the 1200s. He was a hairy man, usually naked, who lived outside of civilization—but not so distant from it that he was never spotted. Like a man, he had two legs and two arms and he stood upright, but he wasn’t always exactly human. He had a lot in common with the mythic fauns, which were half-man, half-goat, and sometimes was linked to pre-Christian deities.

But by the 1500s, the wildman had been layered into Christian ideas, as a feral man, living outside the influence of religion, a sort of Tarzan for the medieval period. Wildmen appeared at Carnival time (and still do, as lichen-dressed, yeti-like creatures), and appeared in engravings where they used their giant, gnarled wooden clubs to fight with more civilized men. Even more modern coats of arms that feature wildmen (and women) bestow caveman-like clubs on them.

Some scholars, like Stoczkowski, make a direct connection between the club of the caveman and the club of the wildman. “Humans of the earliest period were soon cast in the same role,” he writes. And those pre-historic cavemen “inherited [the wild man’s] attributes, and, oddly enough, the club.”

But cavemen may not actually have inherited the club so directly from wildmen. It’s a tempting jump to make: here are two hairy, underdressed archetypes, each holding a club. Surely the European imagination must have taken the club from the hand of the wild man and placed it in the hand of the caveman?

The timing, though, doesn’t quite work. As Gregory Forth, an anthropologist at the University of Alberta, points out, the wildman’s popularity in Europe dwindled after the 16th century, and there’s a huge jump in time from that moment to the creation of the “modern” caveman, in the late 19th century. Neanderthal man wasn’t discovered until 1856, and by the time cavemen came into existence as a part of popular culture, wildmen were a shadow of their former selves.

At the same time, since the heyday of wildmen, Europeans had encountered all sorts of new people, myths and hominids. As they explored the world, they met people of different cultures, who often had their own versions of apocryphal hairy men living outside civilization. They also encountered gorillas, orangutans, chimpanzees, which may have been the distant-past inspiration for European wildmen to begin with. In this period, the European conception of wildmen got muddled with racism, ideas about “primitive” man, and attempts to understand apes.

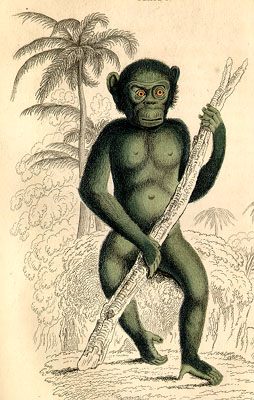

And if wildmen carried clubs in the medieval ages, by the Enlightenment, they had passed them onto apes: in the 18th century, apes were often pictured carrying wooden staves to help them walk upright.

A staff-carrying ape (Image: Sir William Jardin)

“I think that this kind of idea was transposed onto the image of prehistoric humans, like Neanderthals,” says Forth. “For a very long time, Neanderthals were depicted as not being able to stand up fully erect or to walk properly. Hence the need for something wooden to hang onto.”

By the 19th century, Europeans had conflated these ideas of apes, pre-historic humans and hunter-gatherer societies into a generic image of primitivism. And that’s what novelists drew on in the 1890s and early 20th century when they started pulling cavemen into popular fiction and film. Soon club-wielding cavemen were populating a whole genre of fiction set in pre-historic times or lands that had missed the modern era, like The Lost World.

It wasn’t long before that style of caveman broke into film, either: his first appearance was in 1912, in Man’s Genesis. In this short film, a caveman named Weakhands vies with another, Bruteforce, for the affection of a cave woman, Lillywhite. Bruteforce has the upper hand, until Weakhands invents a weapon that will win him the girl. It is, of course, a club.

In the past century, it’s become natural for cavemen to carry cartoonish clubs, thin on one end, bulbous on the other. (Even the Lego caveman has his own Lego club.) There’s little evidence that clubs were ever a weapon for ancient humans; that they carried these weapons is little more than inference. But even if they did have clubs, it’s easy to imagine that club-carrying early humans lost out to peers carrying spears–which could be used to attack from a distance and, as a bonus, definitely existed.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook