The Art of Chinese Propaganda Posters

A glimpse inside the collection of Shaomin Li, artist and dissident.

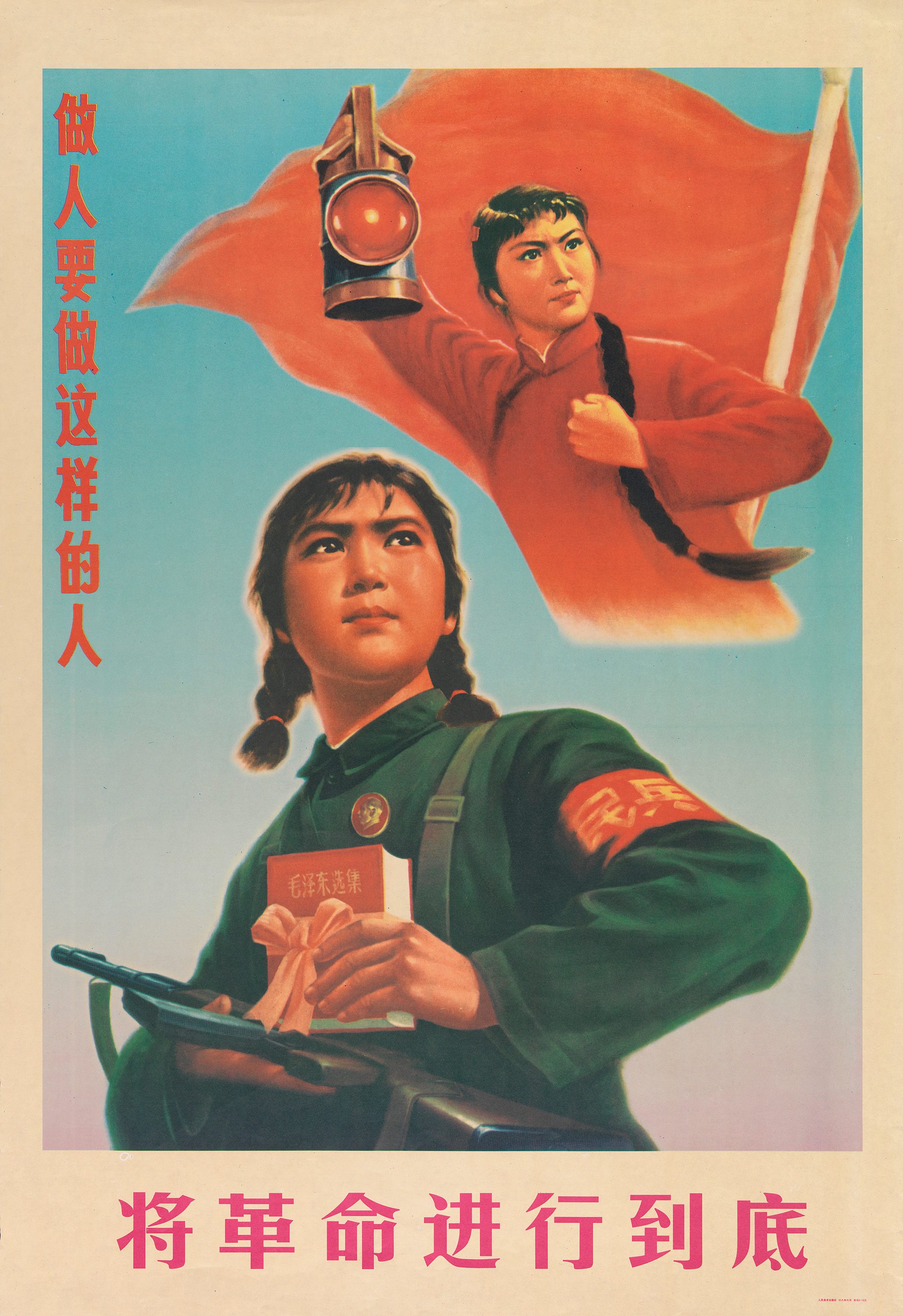

Propaganda posters can leave a lasting impact. For Shaomin Li, the Chinese artist, economist, and dissident, they are particularly meaningful. He grew up during the Cultural Revolution, surrounded by the posters that he now collects. As a soldier in the People’s Liberation Army, Li also had to create them. Now, some of his collection is on display in a new exhibition at the Chrysler Museum of Art in Norfolk, Virginia.

“For my generation, our education was pretty much Mao’s revolutionary class struggle ideology, which was propagated by the posters,” says Li, in an email interview. “It has left such a strong indelible imprint on us that many of us may still subconsciously follow Mao’s tactic in our lives. For example, many contemporary business leaders in China attribute their business success to Mao’s thought.”

Li grew up during the Cultural Revolution, a 10-year period of destruction and upheaval in China. It was launched by Mao Zhedong in 1966 as a way to reassert his rule and galvanize the Communist revolution, with a devastating impact. The death toll is usually estimated at one million, although one study suggested it could be as high as eight million. It also encouraged the eradication of the “Four Olds”—old “things, ideas, customs, and habits,” through which classical literature, art, and architecture were damaged or destroyed.

“Whenever I think about that era, the scene in my mind is a red ocean of posters, with high-volume speakers blasting fighting slogans and songs praising Mao,” recalls Li. “It was surrealistic. The masses were totally mobilized by Mao to destroy everything that was not revolutionary. Remaining calm and normal was dangerous and was viewed as crazy and abnormal.”

“Shaomin Li’s collection really traces how the Communist Party penetrated all aspects of life in China during this period, and he brings unique insights because of his life story,” said Lloyd DeWitt, the Chrysler Museum’s chief curator, in a statement.

In 1975, Li joined the People’s Liberation Army as an artist-in-residence. “I loved drawing and painting when I was very young,” Li says. “Later on, I became a propaganda poster artist not by my own choice—in that era, every artist must do propaganda work, because Mao told us that art is merely a tool for the revolution.”

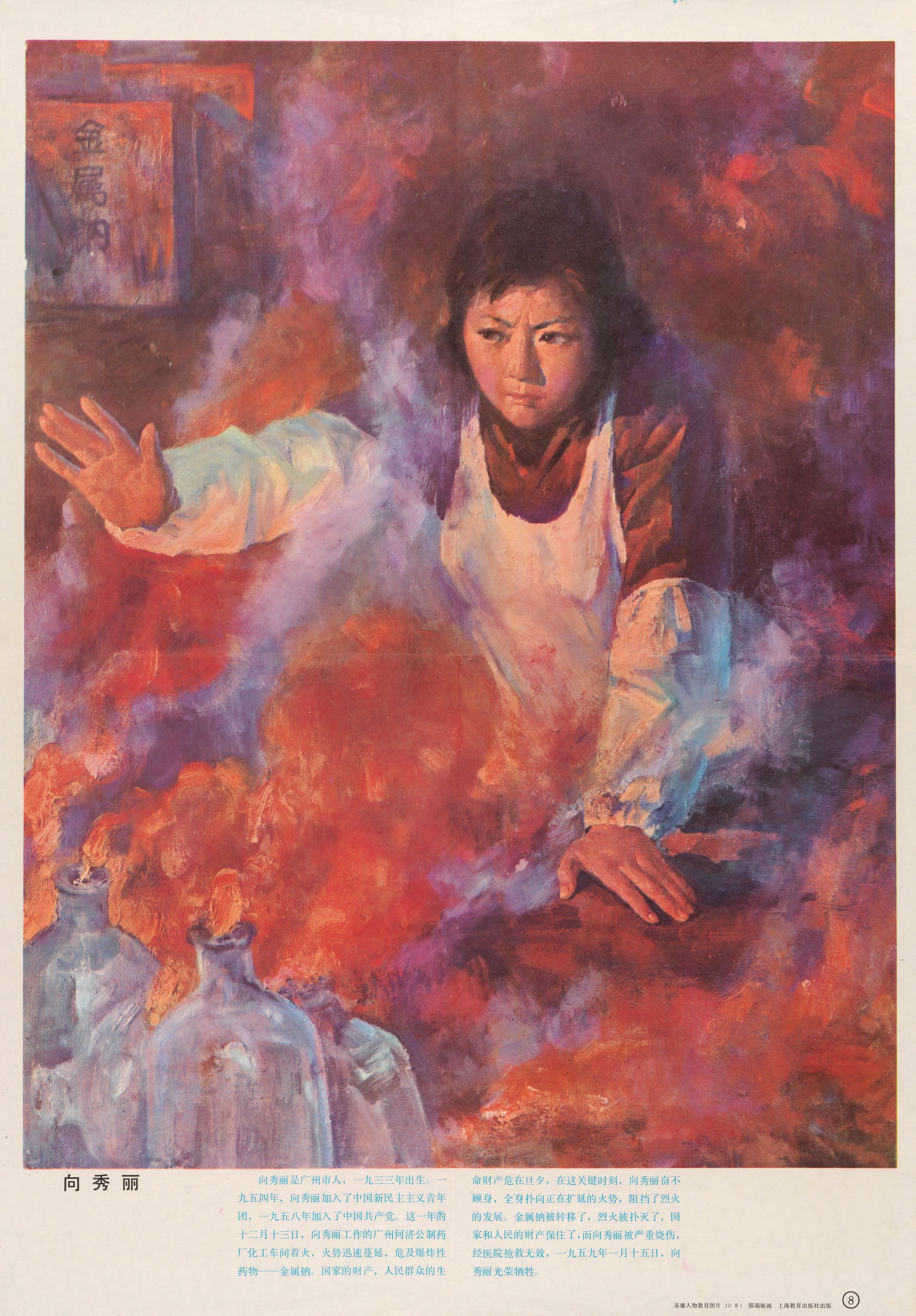

The content of the posters were strictly regulated: he could only draw approved imagery, which was set out in model books. “I focused on portraits,” he recalls. “Under Mao, the main task of art is to depict and glorify him and other revolutionary heroes.”

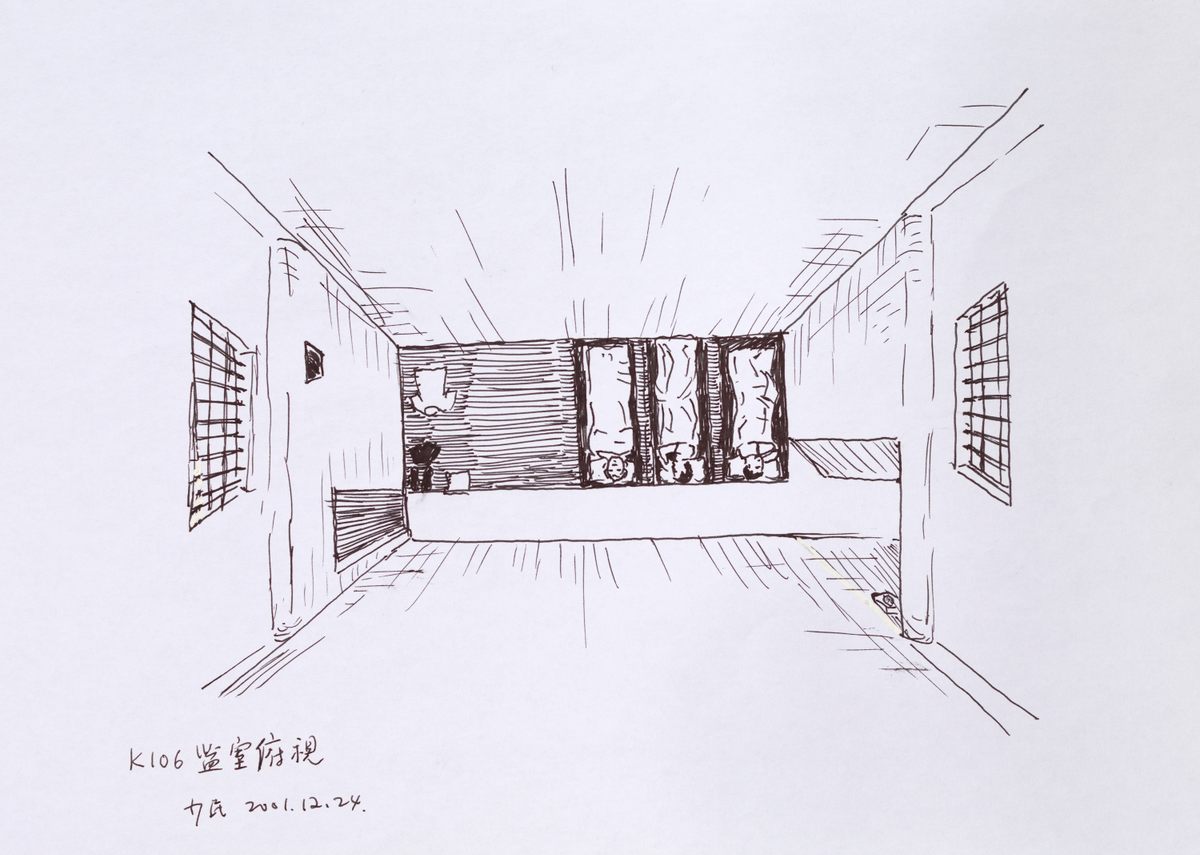

Li was eventually demoted from this position for a “bourgeois tendency,” and was serving as a soldier when Mao died in 1976. Then aged 19, Li was called upon to paint Mao’s funeral portrait. Although this was perceived as an honor, it was also fraught. Li later wrote, “One small mistake might send me away—yet not back to guard post duty, but to be guarded in detention for desecrating Mao’s god-like image.” Despite these risks, Li’s painting was well-received; there was even a photo taken of him next the portrait, a rare occurrence in China at the time.

This photograph is also part of the exhibition, alongside a much later sketch of Li’s: a drawing of the prison cell in which he was held captive for five months in 2001. He had been arrested on a trip to China for promoting democracy in Hong Kong—or “endangering state security,” according to the charges. After his eventual release, Li left Hong Kong for the U.S, where he’s now a professor at Old Dominion University.

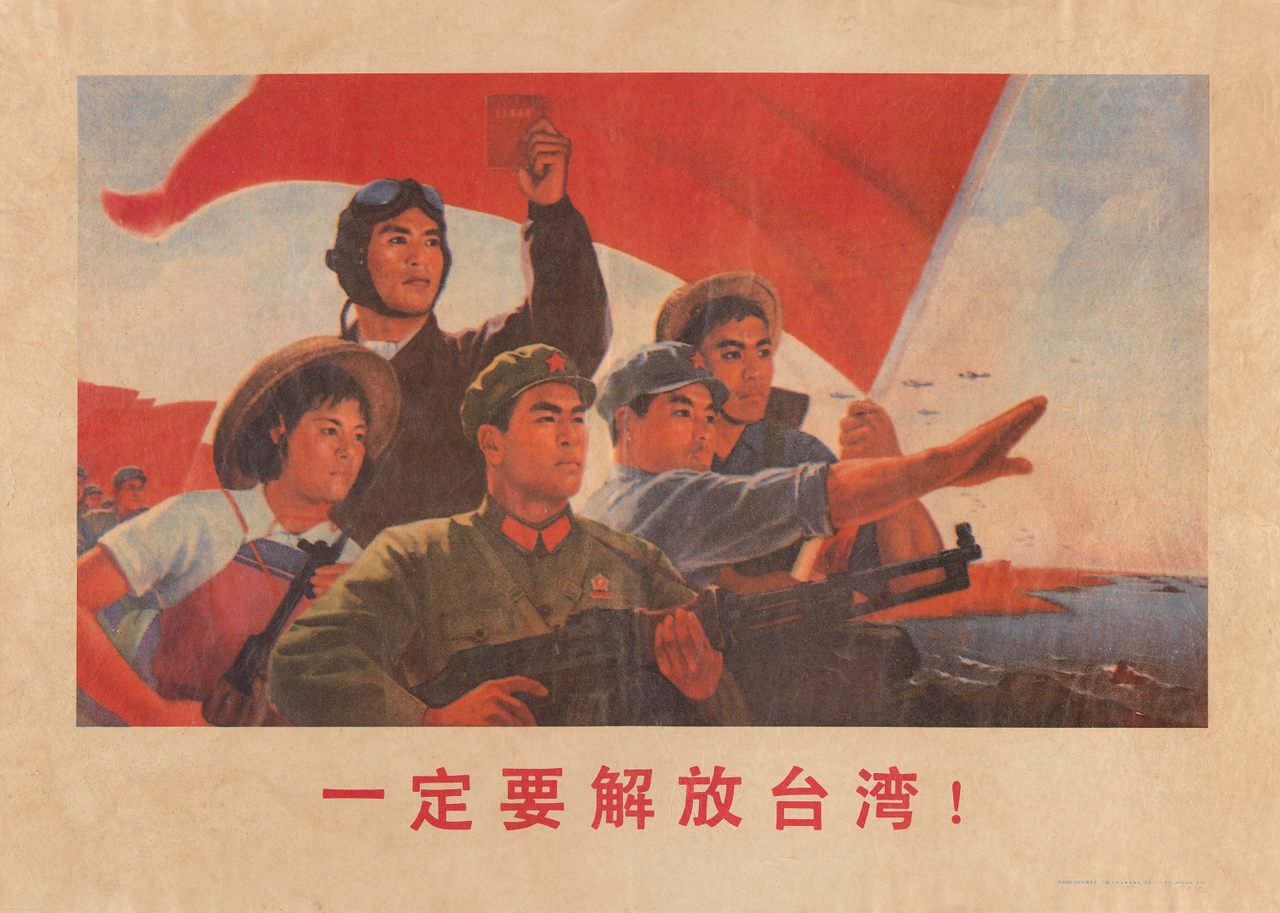

For Li, there is a timeliness to this exhibition. “We thought that the Chinese Communist Party had learned a lesson from the mistakes of launching the Cultural Revolution, and would totally repudiate it. But we were wrong,” he says. “Some of the practices of the Cultural Revolution, such as mobilizing the masses to worship the top leader, suppressing and drowning any dissenting voices by the red ocean of posters and slogans, are having a comeback. So by showing what happened during the Cultural Revolution, we can better understand what is happening there today.”

DeWitt also sees a broader context. “We would like visitors to be aware of how a dictatorship happens,” he says. “It destroys the past and plays on fear and emotion, as well as identity.”

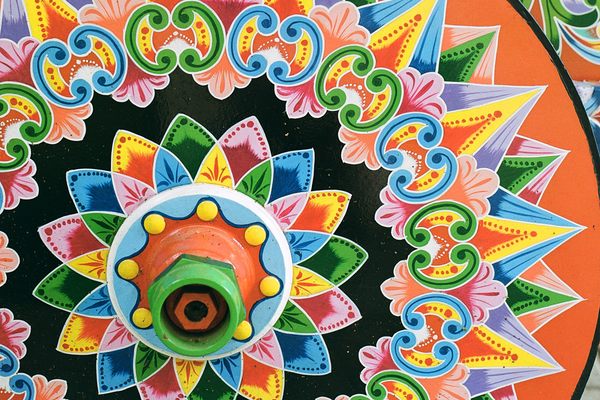

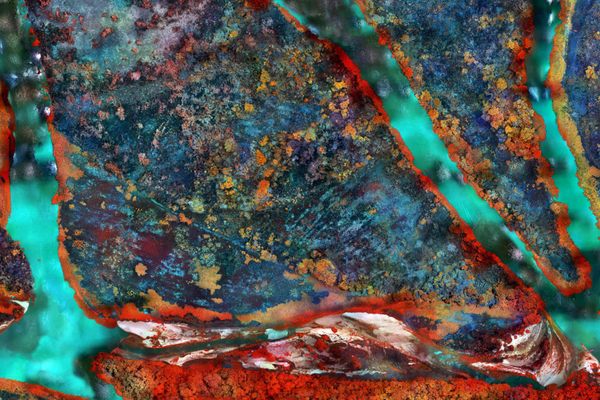

AO has a selection of images from The Art of Revolution—which includes posters from after the Cultural Revolution—and which runs from March 2 through to June 24, 2018.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook