The Pioneering Mountain Climber and Skier Who Filmed Her Own Exploits

Her work is now available as part of a project to digitize home movies made by women.

It was the second week of May, and when they arrived at Banff, in Alberta, Canada, Christine L. Reid and Benno Rybizka feared that the snow might already have melted, foiling their plan.

Two ski seasons had already passed since they had decided to make a ski film—a novelty in the 1930s, when skiing was still a relatively new sport. Rybizka, a renowned ski instructor from Austria, would provide the demonstration, and Reid, an avid amateur skier and filmmaker, would shoot and direct the film. They had along with them two locals—the Edwards brothers, known as Chess and Rupe—to guide and cook for them, plus another local skier and a former member of the University of Zurich ski team. The team had just two weeks to pull it off.

At their destination, they got good news: Up at the Sunshine Ski Lodge, seven feet of snow still blanketed the ground. The next day, they started up the mountain, with a state-of-the-art camera—the “most completely waterproof model on the present day market,” Reid wrote—along with tripods, lenses, and about 2,000 feet of film. As their horses ambled up the slope, toward the snowline, one of their companions started to sing: “Heigh-ho, heigh-ho, it’s off to film we go …”

It was the Golden Age of Hollywood, and home movies and the work of amateur filmmakers was just starting to gain a place in American life—at least among those who could afford the gear, and Reid could. She was raised in a well-off family, and for a woman of her time, Reid had an exceptional life. When she married at the relatively late age of 35, even her bouquet—of edelweiss, bouvardia, and white sweetheart roses—was deemed “unusual” by The Boston Globe.

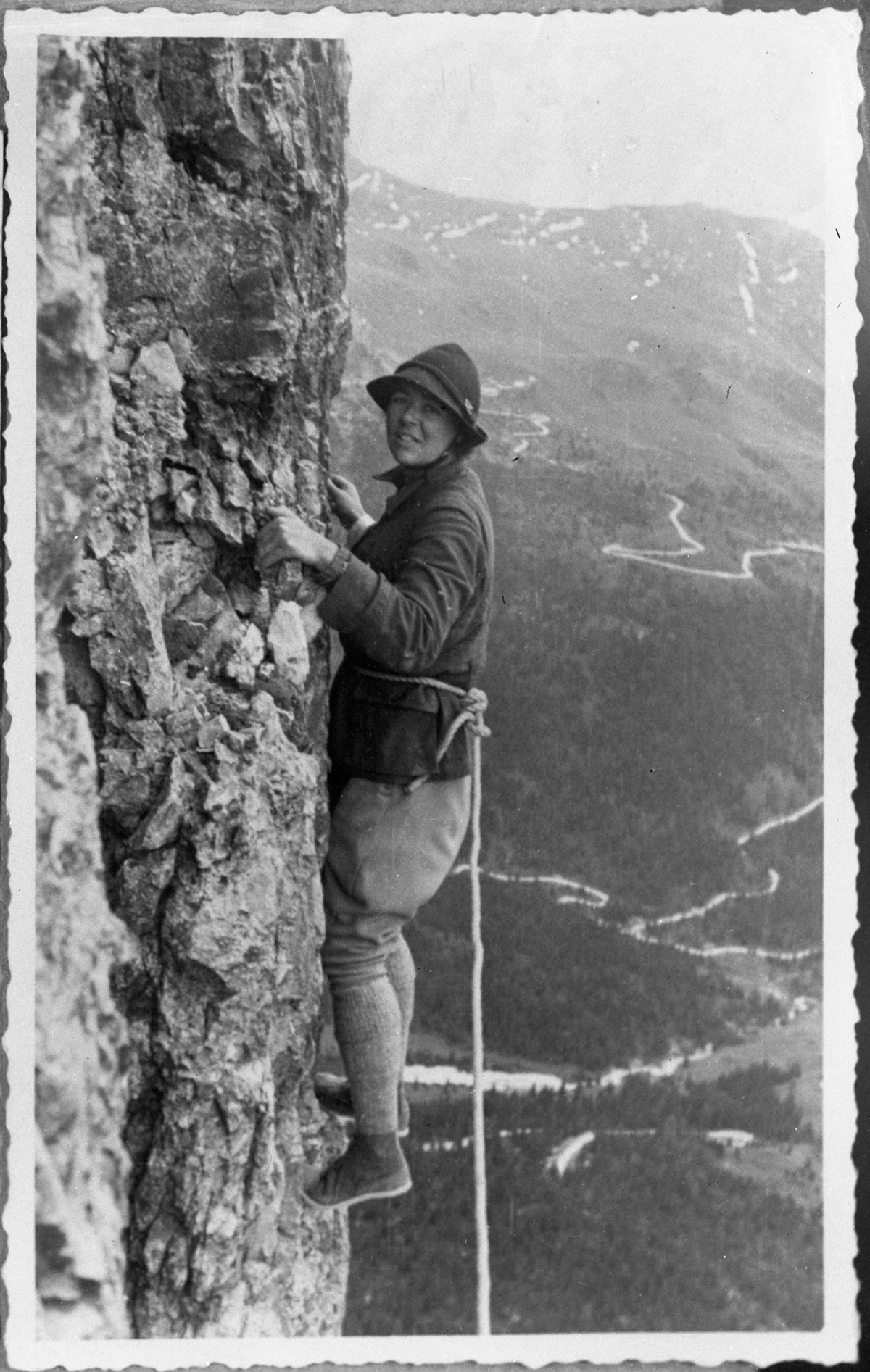

But her first love was mountaineering. She spent her 20s climbing rock faces and in 1938 became the first woman to climb Mount Columbia, the second highest peak in the Canadian Rockies. Later, her passion grew to include skiing and, though there were few women in the 1920s and 30s making films of their own, she dedicated herself to promoting and documenting with her camera the outdoor activities that she’d fallen so hard for.

Today, Reid’s films are part of a project, The Woman Behind the Camera, that’s digitizing home movies and amateur films made by women in the 20th century. Funded by a grant from the Council on Library and Information Resources, the project is a collaboration between Northeast Historic Film, the Chicago Film Archives, and the Lesbian Home Movie Project. The Reid footage comes from Northeast Historic Film’s collection, which also includes pieces made by Dorothy Stebbins Bowles, the globe-trotting wife of a U.S. ambassador; Anna B. Harris, an African-American woman who captured the daily lives of people of color in 1950s Vermont; Mary Dewson, a well-known suffragette; Marguerite Larock, one of the few female lawyers in Maine in the 1930s; and more.

The films provide a glimpse of women’s perspectives in the early 20th century—more directly, perhaps, than any other historical documents from the period. “These films are very intimate,” says Karin Carlson-Snider, the vault manager at Northeast Historic Film and project director for The Woman Behind the Camera. The women were filming what they found important. Then, people often filmed the same subjects they do now—their cats, kids on sleds, family parties, vacations. The Reid collection—hours of film that can been found on Northeast Historic Film’s website—has all of that along with dramatic footage of people climbing some of the world’s tallest mountains.

Reid grew up athletic, with sailing a family pastime, and in 1929, when she was in her early 20s, she climbed her first major mountain, Canada’s Assiniboine, the “Matterhorn of the Rockies,” which reaches 11,870 feet. She was hooked. Soon she began spending her time in the Pennine Alps in Switzerland and Italy, where she climbed every major peak, and the Dolomites in Italy, where a new route on the mountain Piz Popena was named for her. While she climbed with guides and other mountaineers, she also pushed for women to find their own way in the sport, and once led a “manless party” up Mount Confederation in Canada.

Her interest in mountaineering led to skiing—naturally, as what goes up must come down. After landing a gig with the Boston Tribune (and later the Globe) as a ski correspondent, she reported on the comings and goings of ski instructors, ski store openings, “ski wedding bells,” and other stories of the ski season, such as “the mystery of the mussed-up bunk room.” Her writing was jovial and upbeat, and invited her readers to share “a world of outdoor fun.”

The films in the archive look into this world, which was privileged enough to keep the stresses of the Great Depression at bay. In the footage, Reid and her family are sailing, horseback riding through the Grand Tetons, and laughing at garden parties. She also approached films with education in mind. One ski film, made in Europe, shows the very basic techniques of the sport, and in a longer film made in the Dolomites, she had guides demonstrate how mountain climbing works.

Because of their alpine settings, some of Reid’s home movies can be dramatic, and capture moments of elegance and drama. When she and Rybizka reached the Sunshine Ski Lodge in Banff, they spent busy days filming on the slopes. One day, she wrote, they came upon “a magnificent windblown formation, with a long curving crest that reminded one of an ocean wave about to break into foam on the beach.”

With the camera rolling, Rybizka sailed over its brim. “Benno was poised for an instant like some strange seabird hovering in search of its prey,” Reid wrote. She could forget the foggy lenses, the overexposures, the difficulty of fumbling to change reels while wearing mittens. “It is such moments as these which make ski filming worthwhile.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook