When the Star of ‘Dragnet’ Wanted to Start a Show With the CIA

It, sadly, was never made.

A version of this story originally appeared on Muckrock.com.

In 1982, former CIA Director Richard Helms was approached by Dragnet creator Jack Webb about a possible TV show regarding the Agency. Like Dragnet, it would focus on realism, and would be at least inspired by, if not based on, events that had happened. While the show was never made, it’s unclear if this was because CIA Director Casey decided to pass on it or if Webb’s death cut off any progress.

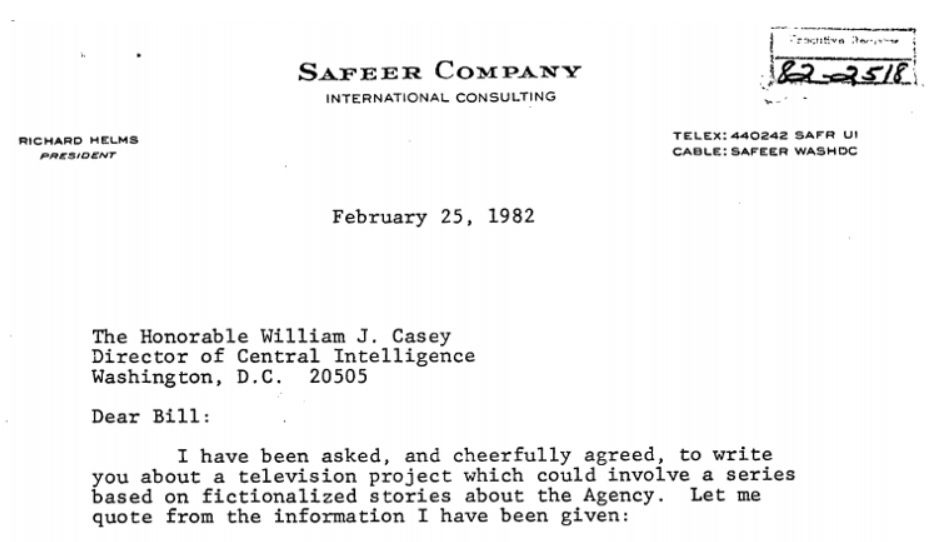

Writing on letterhead for his new consulting company, Helms informed Casey that he had “cheerfully agreed” to help raise the matter with the Agency. (As an historical curiosity, the consulting company was called Safeer Company. Safeer is a transliteration of the Farsi word for “Ambassador”; the next year Helms was confirmed as the Ambassador to Iran.) Helms’ agreement was either so cheerful or so superficial that all but three sentences in his letter are simply quoting someone else - presumably Webb or one of his associates writing in the third person.

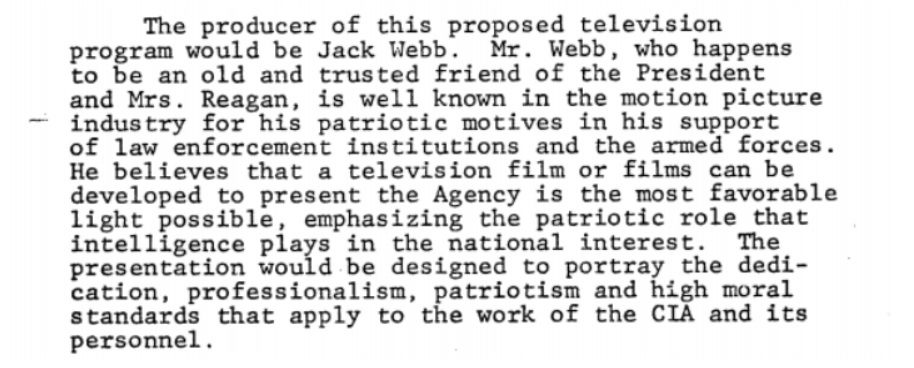

As an actor and producer in Hollywood, Webb had inevitably become friends with then-President Ronald Reagan. In the Reagan age of nepotism, this was considered significant enough to be the second sentence in the quoted section and the first thing the reader is informed about Webb other than his involvement. Not only was Webb “an old and trusted friend of the President,” he was “well known” in the industry “for his patriotic motives in his support law enforcement institutions and the armed forces.” Webb wanted to bring this patriotic sense of duty to television with the Agency by “emphasizing the patriotic role” of CIA and the “high moral standards that apply to the work of the CIA and its personnel.”

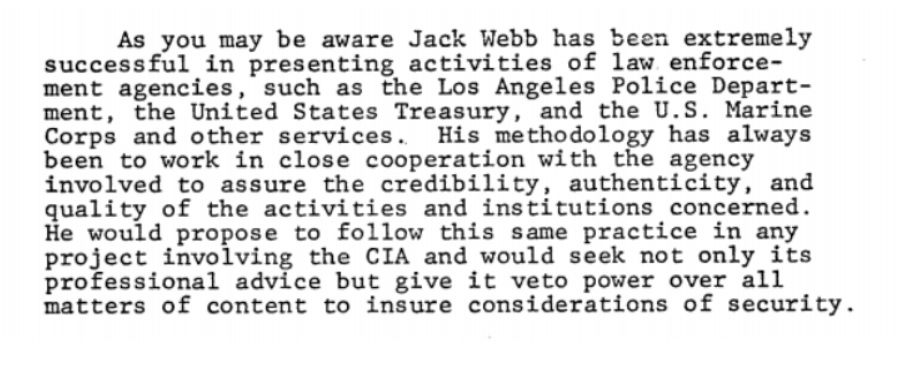

While Webb had been “extremely successful” with his previous presentations which had sought to blend realism with propaganda and PR efforts, he wanted to accommodate the Agency’s needs. To this end, he sought to not only work in “close cooperation” with the Agency and seek its advice, but to give it “veto power over all matters of content.”

Webb’s desire to be transparent may not have appealed to the Agency as much as he’d thought it would - one can virtually feel CIA cringing at the thought of being given “credit” for producing a show about itself.

The letter then went on to make explicit what it had previously just implied—the show would not only show the Agency in a positive light, it would aim to “reverse some of the negative attitudes that have been created by attacks from the media and certain political quarters.” The Agency had an opportunity, the letter argued, to work with “important people in the media” to “support the Agency.”

Helms ended his letter by neither endorsing nor discouraging the project. In his third and final self-written sentence, he simply offered to put the CIA Director in touch with Jack Webb if he so desired.

Whatever Casey’s response was, it was delivered to Helms directly over the phone. No additional memos on the subject seem to have been released in the CREST database. In December of that year, Webb died of natural causes. If the project had progressed at all beyond Casey’s phone call to Helms, then it died with Webb.

The subject must have been frustratingly tempting for the Agency. J. Edgar Hoover had used projects like these and careful rebranding of the FBI to improve its image with remarkable results. It wasn’t until the revelations of COINTELPRO and other Bureau wrongdoings the Bureau’s reputation began to publicly suffer.

You can read the full letter here, or you can take a look at this Dragnet clip to get an idea of the flavor that Webb might’ve brought to a show about CIA.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook