How Coconut Macaroons Earned a Place on the Passover Table

Industrial innovations and a heavy push from Jewish companies helped cement the cookie as a new tradition.

During the Passover Seder, Jews eat from a table filled with symbolic food, such as bitter herbs and matzoh, contemplating the dishes’ relationships to Jews’ escape from Egypt. For most Ashkenazi Jews, who trace their ancestry to Central and Eastern Europe, the rest of the meal includes traditional favorites such as potato kugel, gray lumps of gefilte fish, and other dishes evoking a European motherland. But at the end of the Seder, most Ashkenazim indulge in a more recent addition: the coconut macaroon.

A confection of egg white, sugar, and tropical fruit, the coconut macaroon is not listed in any sacred texts and has no tie to traditional Seder rituals. And yet, in the days leading up to Passover, supermarket shelves consistently stock tins of the cookies alongside matzoh and kosher wine. The story of how this unlikely treat found a place on the Seder table is also the story of a wandering people’s arrival in the oasis of American consumerism. It’s the story of one group of Jews finding a taste of a better life, then giving—and at times selling—that taste to the ones who came after them.

Coconut macaroons are “one of those things that you kind of have to have at Passover if you’re an Ashkenazi person,” says Leah Koenig, the author of Jewish Cuisine.

According to Koenig, one reason macaroons took hold among Jews is fairly obvious: Their ingredients abide by Jewish dietary restrictions. They contain no dairy, and thus can be eaten alongside meat. And since they rely on egg whites to rise, they don’t use flour, a banned ingredient during Passover.

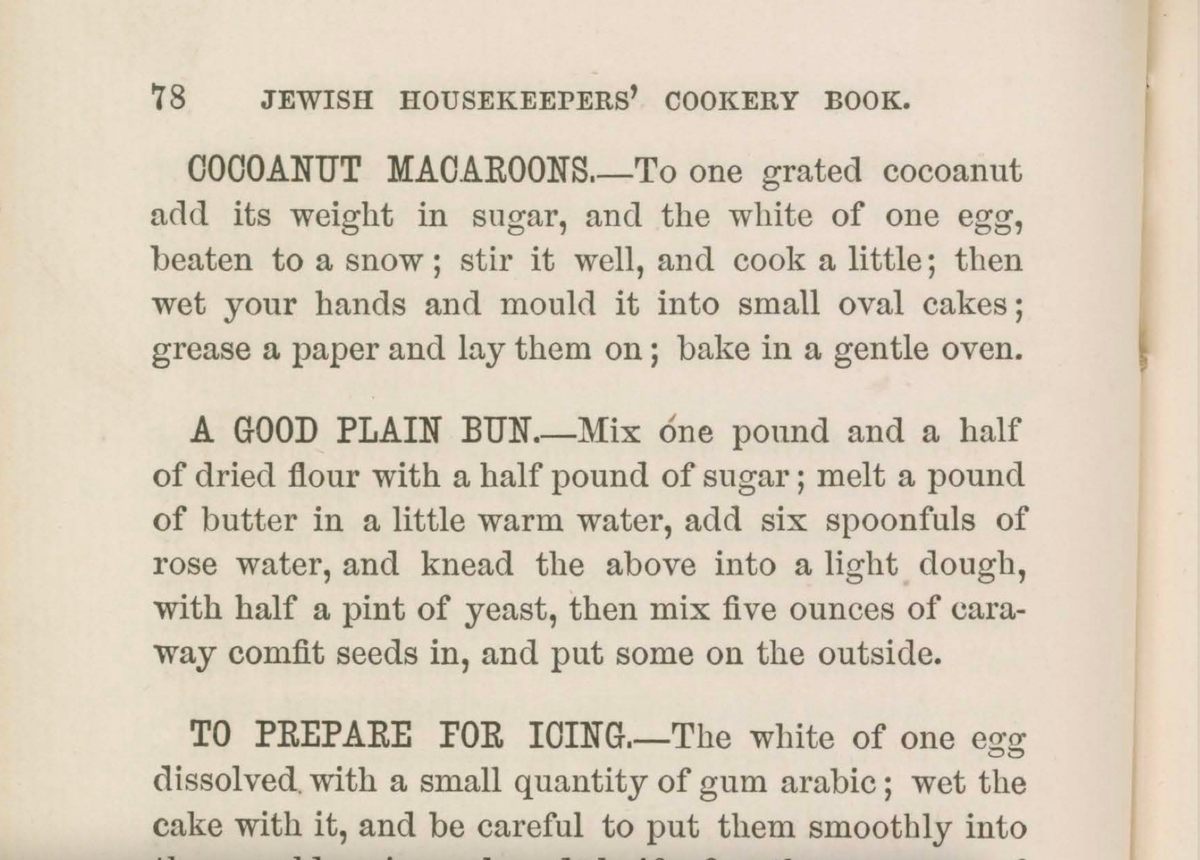

The origins of macaroons stretch back to a medieval-era mingling of Arabic and Italian culinary traditions, but they didn’t appear in a Jewish-American cookbook until 1871. The first Jewish cookbook published in the United States, Esther Levy’s Jewish Cookery Book, includes recipes for traditional almond macaroons as well as versions that swapped dried, shredded coconut for the standard nuts. Koenig says that coconut, which shows up in cookie and cake recipes throughout Levy’s book, would have seemed exotic to American Jews at the time. Difficult and expensive to acquire, the ingredient would have been available only to elites.

Levy likely appreciated coconut macaroons not only for their adherence to Jewish law, but also for coconut’s sophistication. Jewish Cookery is clearly directed at an upper-class audience, offering readers advice on topics like managing hired help: “Much confusion and trouble are saved when there is company,” Levy writes, “if servants are required to prepare the table and sideboard in a similar manner, daily.”

By the time Levy wrote her cookbook, Jewish immigrants from Germanic-speaking parts of Europe had established a number of civic and religious organizations, and founded American Reform Judaism, a movement that advocated for assimilation. It’s impossible to know Levy’s intentions but Jewish Cookery’s recipes for mainstream American dishes such as gumbo, waffles, and ginger snaps would have aligned with the aspirations of this group.

Although coconut was out of the reach of working-class Jews at the time of Levy’s cookbook, that started to change around the turn of the century. In the 1880s, American and British inventors developed machinery that could shred and dry coconut to be shipped en masse. Now armed with a steady, affordable supply of coconut, companies capitalized on the resource and marketed it to a new demographic: The steady influx of working-class Jews from Eastern Europe that started arriving to the States in the same decade.

Fleeing segregation, discrimination, and waves of state-sponsored pogroms, these more than two million Jews were on the brink of annihilation in Eastern Europe. “They felt like they couldn’t go back,” says Matthew Goodman, author of Jewish Food: The World at Table.

As Eastern European Jews arrived in the United States, the already-established German-Jewish community founded aid organizations to teach the new immigrants life skills, including what some viewed as “modern” cooking skills. One such educator was Lizzie Black Kander, a German-Jewish reformer. Her 1903 Settlement Cookbook was meant to serve as a guide for her Eastern European cooking students. It included recipes for “coconut kisses,” which were essentially coconut macaroons.

Koenig says that around this time coconut would have been a symbol of success for these immigrants. “Having choices meant a lot,” she says. “Going from Eastern Europe where you were very limited in what you could have, and your resources were very limited, to America where all of a sudden you had within a generation more wealth and more accessibility … it would have meant, in a way, making it.”

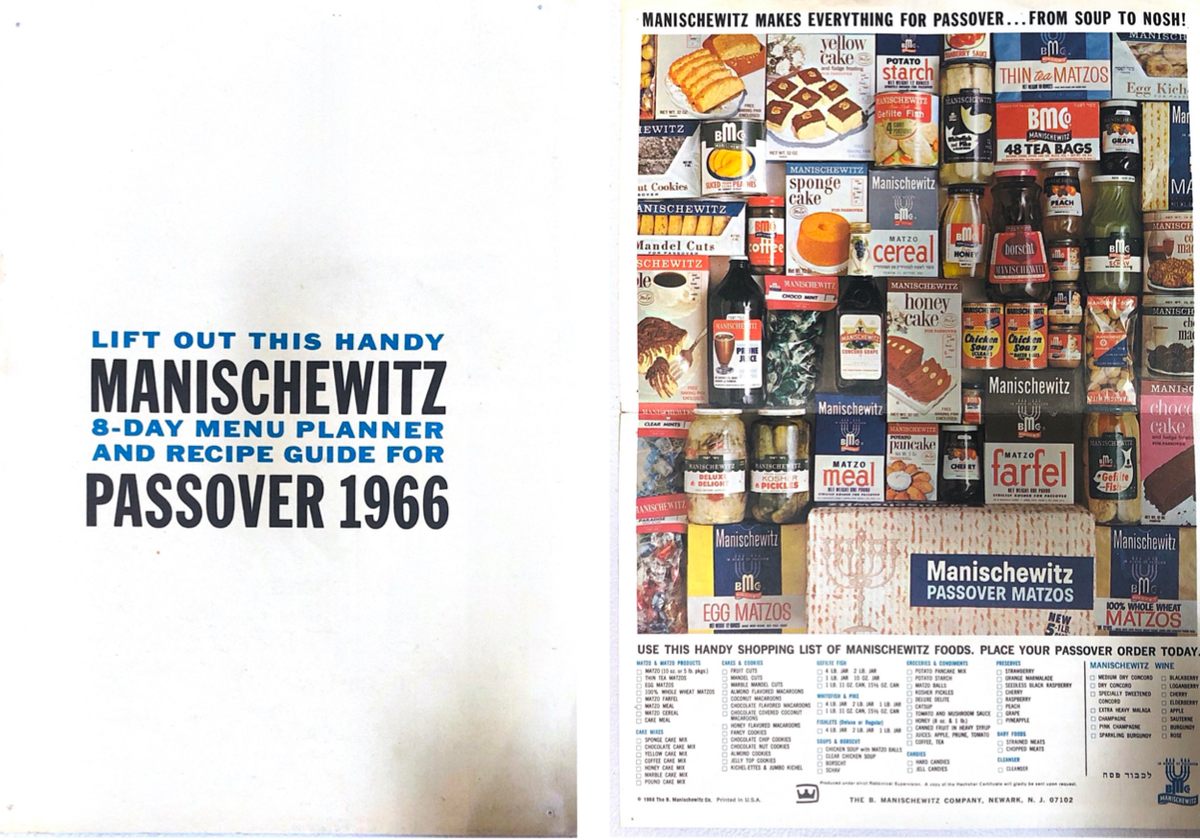

By the 1910s, Jewish-owned department stores started promoting coconut macaroons as a Passover treat. Its appeal went beyond its kosher ingredients: In ads, the coconut macaroon is priced at as little as 40 percent of its almond counterpart. Goodman notes that these department stores were owned by German Jews who “had the marketing ability to be able to create demand for things” in the Jewish community. It worked: By the 1930s, matzoh manufacturer Streit’s added premade coconut macaroons to its offerings, and Manischewitz followed soon after.

Still, until World War II, most American Jews baked coconut macaroons more than they purchased them. “Baking was prized among Jewish women,” food historian Roger Horowitz explains, and coconut macaroon recipes abound in publications throughout the early 1900s. In the 1935 Passover issue of the Kosher Food Guide, a widely distributed pamphlet that helped observant American Jews navigate supermarkets, five different Kosher brands of “Dried Fruit (shredded coconut)” are featured for home bakers, compared to only one advertisement for macaroons.

All this changed during World War II, when Manischewitz put serious advertising heft into selling packaged macaroons for sending to Jewish troops overseas. In 1945, Manischewitz placed its first Passover macaroon advertisement in the Kosher Food Guide. The ad features almond macaroons, likely because wartime shortages took coconut off shelves. “Order early to send to your boy in service,” the advertisement reads. Manischewitz seems aware of the coup it stages against home bakers. The ad assures readers “these macaroons are soft and delicious, just like macaroons fresh from the home oven.”

In the processed food boom of the 1950s, Manischewitz started to advertise coconut macaroons cans in images of modern Passovers. Around the same time, recipes for macaroons were fading from Jewish cookbooks. Horowitz points to the omission of a coconut macaroon recipe from Leah Leonard’s otherwise incredibly comprehensive, 497-page Jewish Cookery, published in 1949. “By that point, macaroons are the kinds of things you buy from Manischewitz,” he says.

After years of coconut shortages, Americans welcomed coconut macaroons with open arms. In 1947, the New York Times reported that “staples that had been imported before the war (coconut, tapioca) returned to shelves … the shredded coconut that … is a macaroon’s reason for being began again to flow into the country.” Jews who once baked coconut macaroons for a taste of exoticism now found themselves purchasing the cookies to return to normalcy.

Today, that sense of normalcy has matured into full-blown nostalgia. Manischewitz still sells its coconut macaroons in cans, a representative says, because “we feel that it is the traditional way.” At the modern Passover table, the cookies also serve as a symbol, not of a people’s flight from ancient Egypt, but of their new traditions in a new promised land.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook