Before Drinking Coffee, People Washed Their Hands With It

This mysterious ingredient was often found in medieval Arabic books of medicine and botany.

In the 15th century, a compelling new drink became the talk of the Near East. Called qahwa in Arabic, it was none other than coffee. But people in the region had been using coffee long before that. Only, not as a drink.

Jeanette Fregulia, in her 2019 book A Rich and Tantalizing Brew: A History of How Coffee Connected the World, cites recent archaeological findings by an American-French team that establish “an ancient botanical origin” for Arabica coffee in southwestern Ethiopia. That the birthplace of Arabica coffee is in the Bonga region is hugely significant, since it may have led to the Ethiopian and Arabic words for coffee beans, buna and bunn.

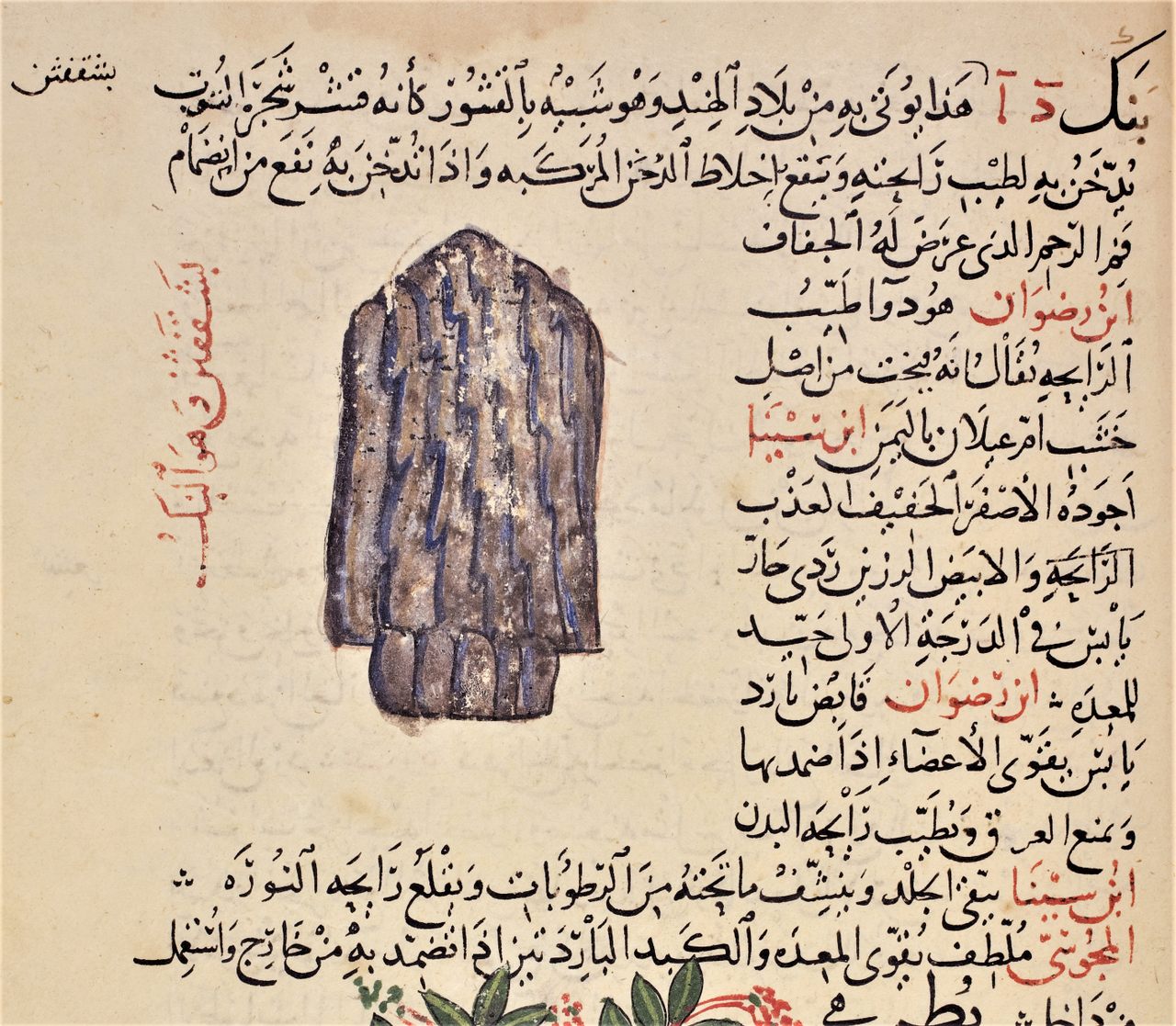

But five centuries or so before the popularity of coffee as a hot beverage, a mysterious ingredient began to appear in Arabic books on medicine and botany. The descriptions of this ingredient were very similar to our familiar coffee. However, instead of bunn, it was called bunk, and rather than drinking this ingredient, it was mostly used for cleaning and freshening the hands.

Numerous surviving early medieval Arabic resources, ranging from books on botany, dietetics, and perfumes describe the uses of bunk. The earliest dates to the 9th century, when Abbasid physician Ibn Māsawayh included bunk in his treatise about aromatics, Jawāhir al-ṭīb. He said it was brought from Yemen, and noted that it was used for making dry, aromatic compounds for women. However, he confusingly identified it as the trunk wood of a tree called umm ghaylān (today recognized as a variety of acacia, Acacia gummifera Willd).

None of those who described bunk in medieval times seemed to have seen it growing in its own habitat. It was likely that the beans were exported from Yemen to urban centers, where it was valued for its medicinal benefits and the pleasant aroma brought out by toasting. In a similar vein, merchants imported tea from China in thin black sheets. Instead of drinking it for pleasure, doctors prescribed it to treat headaches, and applied it topically to treat heat-related swellings.

For the few centuries that followed, bunk was repeatedly described by writers, who occasionally mentioned its qualities and uses. The most enlightening are the 10th century physician al-Rāzī’s comments that bunk was used to check the unpleasant odors of sweat and the smell of the quick-lime used in baths to remove hair. To this, the famed physician Ibn Sīnā added that it could purify the skin and sweeten body odors. Ibn Sīnā also noted that consuming bunk had mind-altering properties, “which could affect the intellect.” For the first time, someone had pointed out the impact of caffeine on the mind.

But doctors considered bunk most useful in making hand-washes, given its capacity to absorb odors and dry up dampness. The earliest recipes using bunk survive from the 10th century, in Ibn Sayyār al-Warrāq’s Kitāb al-Ṭabīkh from Baghdad and a treatise on perfumes and aromatics, Kitāb fī Funūn al-ṭīb wa-l-ʿiṭr, by famous Tunisian physician Ibn al-Jazzār. In some recipes for hand-cleansing preparations, it was used along with a host of other ingredients, such as cloves, black cardamom, fruit peels, cinnamon, and more. Recipes where bunk was the principal ingredient were called bunk muḥammaṣ, which hosts offered to guests to finish off a refined dining experience.

But let’s allow the renowned 10th-century Abbasid gastronomic poet Kushājim to describe this substance for us, highlighting its smooth texture and brownish color and its cleansing properties:

Bunk obliterates greasy smells of food on hands and whatever of sweets and fats. Whether traveling or at home, neglect not to wash your hands with it

When the nimble server passes around with it.

Nothing surpasses bunk to wash the hands after having a fragrant scrumptious meal.

Like musk in color, and soft as silk on hands and face.

(Annals of the Caliphs’ Kitchens)

Fast forward to the 15th century, and the entire Near East was abuzz with energetic discussions and disputes about qahwa—a name that was originally used to designate a dark and strong variety of wine. At the time, coffee was consumed in two ways: as qahwa bunniyya, where the coffee beans were toasted first, then ground and brewed. Qahwa qishriyya, on the other hand, was made by lightly toasting the husks of the berries, the qishr, and then brewing them. Its popularity was further enhanced by the common belief that coffee had medicinal benefits, ranging from drying up phlegm and relieving colds to dissolving kidney stones.

Those who wrote about coffee at the time resorted to legends to explain the origins of drinkable coffee, such as the one that tells how the ancient King Solomon was the first to make the brew. He ordered his jinn to fetch coffee berries from Yemen, which were then parched and made into a drink that could cure illnesses. After this, it was speculated that coffee was forgotten only to be rediscovered by the Sufis, who valued it as an aid for their long night vigils.

A 1558 treatise entitled ʿUmdat al-ṣafwa fī ḥill al-qahwa, by Muslim jurist ʿAbd al-Qādir al-Jazīrī, is the earliest surviving record of coffee as a drink. It was primarily written to discuss if coffee-drinking was religiously acceptable. But it also told the story of its “discoverer,” a Yemeni Sufi named Sheikh al-Dhabḥānī. While in Ethiopia, the story goes, al-Dhabḥānī saw people consuming coffee. Later, back in Yemen, he fell ill and made a drink with coffee beans for himself. It made him feel good again; not only that, but he also noticed that it boosted his energy and helped keep him awake and alert. He spread the word among his Sufi brothers, who valued it as an aid for their long night vigils and spread its use wherever they went.

As for coffee as a hand-cleaning product, it seems that the spread of good-quality colored and perfumed soaps eclipsed its popularity. As bunk itself faded away, so did the knowledge of what it was used for. The first to make a connection between the berries used for making coffee and the bunk used for hand-washing was the famous German physician and botanist, Leonhard Rauwolf.

Rauwolf was the first European to write about coffee in general. He saw coffee beans being toasted and brewed in Aleppo during his three-year visit to the Levant from 1573 to 1575. As scholar Karl Dannenfeldt wrote in 1968, Rauwolf identified the beans “by their virtue, figure, looks, and name” as being the same substance mentioned centuries before in the writings of Ibn Sīnā and al-Rāzī. In other words, they were bunk.

It is worth mentioning, though, that people today are once more awakening to the fact that ground coffee is useful for deodorizing refrigerators and freshening the air. Some people even swear by rubbing their hands with grounds to get rid of odors like garlic, onion, and fish—an idea not too far off from how the ancients used their bunk.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook