Cold War Spies Sifted Through Used Soviet Toilet Paper In Search of Clues

Operation Tamarisk has been called one of the most successful spy operations of the era.

A British patrol car passes an armored East German vehicle on a street straddling East and West Berlin in 1961. The border runs between the two vehicles. (Photo: CIA/Public Domain)

On a cold dawn in East Germany in 1981, two British secret agents crawled through enemy territory in search of intel. Specifically, these highly-decorated spies were scouring the Soviet training field to find soiled toilet paper.

Cold War-era espionage seems as though it would have been a more glamorous–or at least sanitary–affair. However, some intel you just can’t get from a stake-out or wire-tap. Indeed, one of the most successful Western Bloc spy operations in the Cold War involved agents rifling through the enemy’s bloodied bandages and discarded bathroom supplies.

Operation Tamarisk began during the Soviet-Afghan War, which was waged from December 1979 to February 1989. At the time, East and West Germany were occupied by four powers: the U.S., the U.K., France, and the Soviet Union. Through a reciprocal agreement known as the military liaison missions, the allied nations and the Soviet Union had been permitted to deploy a small number of military intelligence personnel in each other’s territory in Germany.

The missions were originally intended as liaison teams that would ostensibly better the relations between the Western and Soviet occupying forces, but they soon became a legalized form of espionage for both sides.

The intelligence methods used by these legal spies ranged from the basic to the ingenious. To learn more about the Soviet-Afghan War, the British Mission (BRIXMIS) had the idea of rummaging through the dumpsters outside of Soviet military hospitals in East Germany, behind the Iron Curtain. Well-used wound dressings and other items fresh from the ward would be bagged and sent out for analysis. The samples revealed shrapnel from bullets and other weapons, whose sources would then be uncovered following further analysis. BRIXMIS agents also haunted the military graveyards behind the hospitals, and noted the names and dates of deaths of deceased Soviet soldiers.

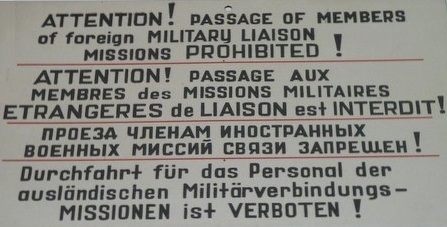

A sign posted in East Germany prohibiting military liaison missions from entering the area. (Photo: Peter Duffy/Public Domain)

The British, French and American liaison teams were banned from visiting areas in East Germany where military exercises were taking place, but once the maneuvers were complete, these areas were combed through, too. In Beyond the Front Line: The Untold Exploits of Britain’s Most Daring Cold War Spy Mission, Tony Geraghty explains, “sifting through the detritus of military exercises, including human excreta and worse, was a valuable technique which sometimes produced gems of intelligence.”

This form of dumpster-diving, Geraghty writes, “had long been sanitized within the Mission under the code-name “Operation Tamarisk.” As a result of the practice’s popularity, “to tamarisk” became a verb in the Mission argot, although at least one British sergeant preferred to describe it as “shit-digging.”

One crucial bit of intelligence that informed the Western Missions as they tamarisked was the fact that toilet paper was not issued to Soviet troops in the field in East Germany. As a result, these soldiers were forced to use any kind of paper they had with them instead. Mostly, they used letters from home–but sometimes they used secret military documents.

These discarded documents were incredibly important to the Western Missions, as they could provide invaluable information on “everything from ciphers to intelligence on morale levels and also on Army-Party-MGB relations in the field,” Richard J. Aldrich writes in The Hidden Hand: Britain, America and Cold War Secret Intelligence.

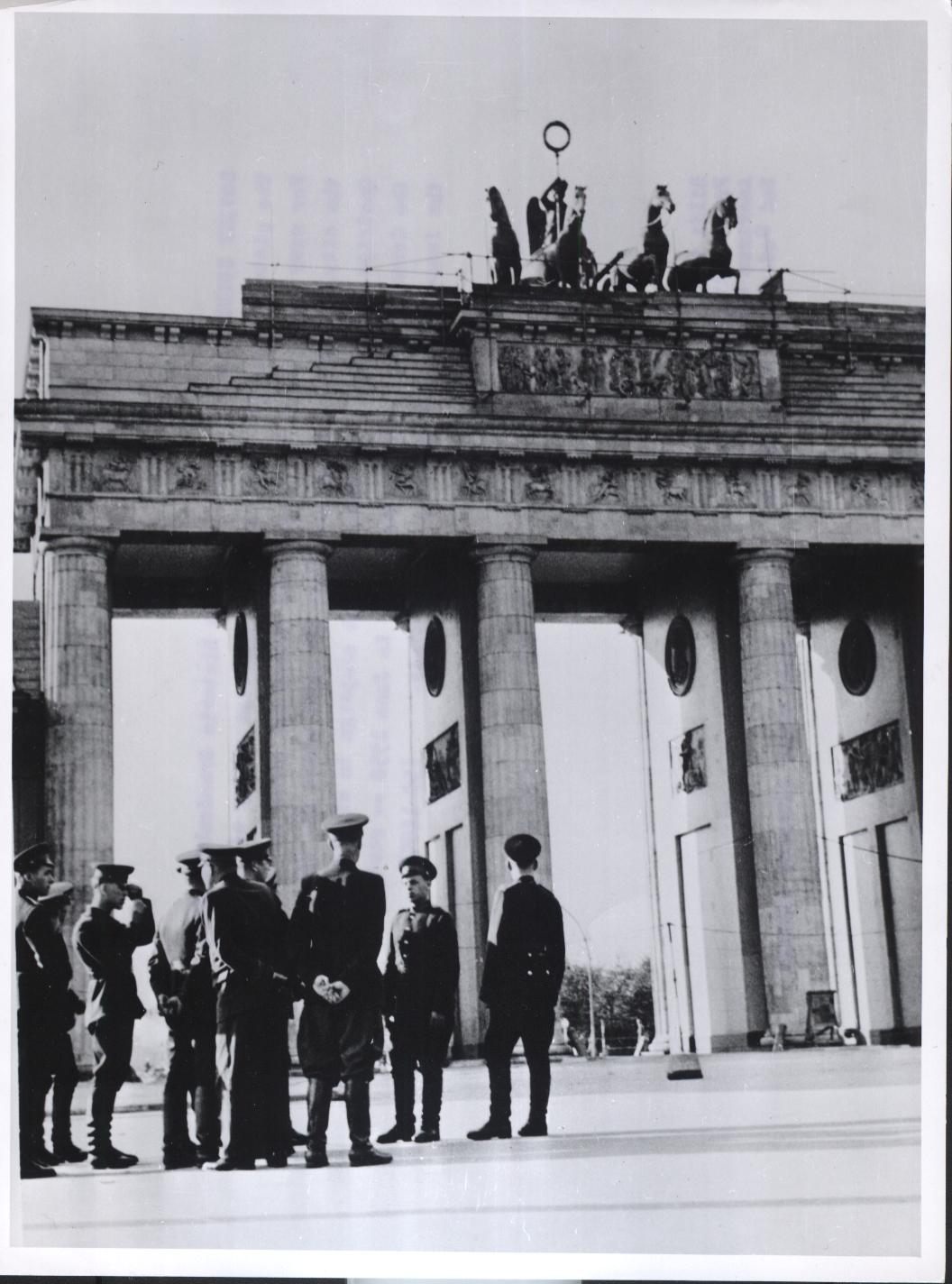

Soviet soldiers stand before Berlin’s historic Brandenburg Gate. (Photo: CIA/Public Domain)

“The untidy habits of the Soviet Army consistently proved to be one of the most startling sources of material,” Aldrich writes. Combing through Soviet exercise areas and firing ranges could produce findings of improvised toilet paper such as “notebooks and schedules of newly arrived material with sources and serial numbers for the latest equipment.”

This information was “gold dust to the growing army of analysts in London and Washington,” Aldrich explains–not that they didn’t make jokes about it, too. Some agents tasked with reviewing the soiled papers had quite a puerile sense of humor and “enjoyed ‘forwarding’ to each other some of these unsavory intelligence items for ‘further analysis.’”

Through one tamarisking mission at Neustrelitz, a quiet place in the north of the GDR, BRIXMIS agents found a Soviet military log that revealed top-secret data about the type of armor, the strengths and the weaknesses of the latest Russian tank, and even contained information about its proposed successor. The information caused a huge stir at NATO’s technical intelligence division, and according to Geraghty in Beyond the Frontline, “set in train an emergency programme to acquire a new anti-tank missile known as the ‘long-rod penetrator’ … [which is] now in service with the British Army.”

Children were not the only ones playing in the dirt in Soviet-controlled Germany–so were Western Mission spies. (Photo: CIA/Public Domain)

Another tamarisking operation undertaken in 1981 had almost as impressive effects. Major Jim Orr, a Parachute Regiment soldier doing a tour with BRIXMIS, alongside Sergeant Tony Haw, trawled a training area near Cottbus that was being used by the Soviet paratroopers. Orr and Haw lay under cover at first light, combing through the Soviet trash. Here, just as elsewhere, they found the same improvised toilet paper.

According to Geraghty, Orr saw a Russian soldier come out to relieve himself in the midst of the operation, and the two agents narrowly avoided being seen. But even though they had to rush away, the two ended up finding “some smelly papers” which were then “reassembled and analysed back in Berlin,” and included “documents revealing the brigade’s training programme, and, even more important, an Order of Battle booklet that revealed some units as a ‘shell’ formations,” writes Geraghty.

“Shit-digging” might not have been as unpopular with agents as you might think. If they dug up something valuable, it helped both their careers and the covert war effort. “I seemed to get landed with a lot of tamarisk operations,” Orr later explained to Geraghty. “Eventually I volunteered for them as a sort of masochistic pleasure.”

Operation Tamarisk has been described as one of the most successful, if lesser-known spy operations of the Cold War. It didn’t involve martinis or Aston Martins, but you know what they say–no guts, no toilet paper, no glory.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook