The Farmers and Gardeners Saving the South’s Signature Green

These seed savers are preserving and celebrating the enormous genetic diversity of collard greens.

In the American South, many people have fond memories of a pot of collard greens simmering on the stove for hours, seasoned with a ham hock and stirred by a parent or grandparent. Cousins to cauliflower and broccoli, collards are a hearty green known for their robust, slightly bitter taste and the rich, nutritious “pot liquor” they produce when cooked. These greens and their liquor have been lauded for generations, but few in the South know that there’s more than one kind of collard green. Even fewer know that there are dozens of different varieties, and that many are now on the verge of disappearing forever.

That’s where the Heirloom Collard Project comes in. By distributing and growing rare and unique collards, this massive collaboration has created ties between chefs, gardeners, farmers, and seedsmen who hope to preserve the plant’s genetic diversity.

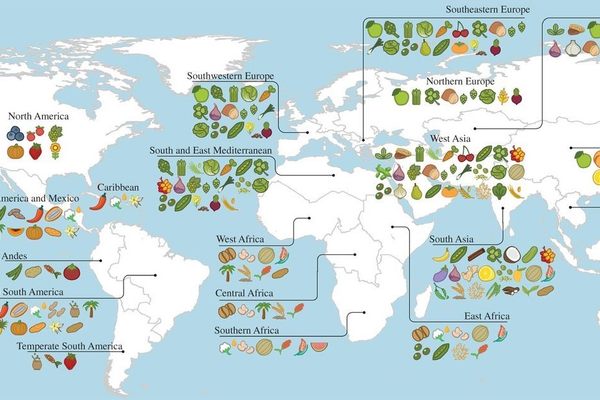

Collards are not native to the United States. Instead, they’re Eurasian in origin, and ancient Romans and Greeks feasted on them thousands of years ago. As for how they became prevalent in the American South, scholars have a number of theories. Collard seeds may have been brought over from Portugal in the 18th century, or from the British Isles to the early colonies. However, the most prevalent theory is that enslaved Africans introduced them to the region, since collard greens were a staple crop in many parts of Africa. Historian John Egerton, in his 1987 book Southern Food, declared that “from Africa with the people in bondage came new foods,” such as okra, black-eyed peas, yams, and collard greens.

Regardless of when or how they arrived stateside, collard greens flourished in Southern gardens. 20 main varieties, from the Yellow Cabbage collard to the Old Timey Green, established themselves as garden favorites. But after World War II, many Americans moved away from both their farmland and their agricultural lifestyles. One victim of this shift was the collard green. With fewer people farming, variety after variety dropped off the map, leaving only five types that could easily be found—Georgia Green, Champion, Vates, Morris Heading, and Green Glaze.

But five years ago, Ira Wallace and the members of the Seed Savers Exchange asked the USDA for over 60 collard green varieties to plant in Iowa. Wallace, as worker/owner of the cooperatively run Southern Exposure Seed Exchange, had been promoting the versatility and resilience of collards for years. Her inspiration for spearheading the Heirloom Collard Project was a series of photos taken by Edward Davis.

Davis and John Morgan, both geography professors at Emory & Henry College, traversed the South to collect rare heirloom collards between 2003 and 2007. The pair published a book on their quest, Collards: A Southern Tradition from Seed to Table, in 2015. They then gave the dozens of collard varieties they had gathered to the USDA. When Davis shared photos of all of the collards he tracked down, Wallace knew she wanted to help make the seeds widely available once more.

The project has several goals, among them seed preservation, documenting the stories of the still-living seed stewards that Davis and Morgan met while writing their book, and, perhaps most importantly, providing seeds to companies and gardeners interested in growing these storied old varieties.

So far, many have risen to the challenge. That’s according to Chris Smith, the James Beard award-winning author of The Whole Okra, executive director of Utopian Seed Project, and participant in the Project. At the moment, he explains, “there are eight farms that grew 20 varieties of collards this past fall, and 100 participants [currently] have three varieties growing in their backyards.” Participants document data on the growth, flavor, and yield of their collards, with the goal of better understanding the unique features of each variety.

Smith calls this interest in collards a return to form, especially in the South. “Everyone used to have a patch of collards, and I’m hoping more people are thinking about food security now that we’re living in crazy environmental times,” he says.

Comfort Farms, in Milledgeville, Georgia, is currently growing collard varieties provided by the Project. Founded by former U.S. Army Ranger Jon Jackson, the farm employs veterans to grow heirloom vegetables and raise heritage animals. Growing 20 different kinds of collards has been “a huge awakening,” says Jackson. “We live in the South and folks only think about Georgia collards,” he gushes. “They don’t know about any of these amazing collards.”

Each collard green in the project has its own distinguishing qualities, as well as a story. The Old Timey Blue collard has both large bluish leaves and vibrant, pink-purple stems. The North Carolina Yellow collard tastes like broccoli, and lacks the usual collard bitterness. The Big Daddy-Greasy Green collard has both an incredible name and story behind its preservation. Hansel Sellars of Cairo, Georgia grew this variety for 50 years before giving some seeds to Davis. He himself had originally purchased two tablespoons of the seeds in 1955, for two dollars.

The Heirloom Collard Project is especially meaningful to Jackson, considering the significance that collard greens have in African-American cuisine. By planting these endangered varieties, he’s carrying on the painstaking work of past Black farmers. “I’m growing collards in a state of empowerment,” he says, a thought that he muses might not have occurred to his ancestors, who grew them for sustenance. Jackson also subscribes to the theory that enslaved Africans brought collard greens to the United States, which gives the project even more pathos. “When we talk about how to connect Black folks with our culture, the one thing that wasn’t ripped away is the food that we brought with us,” he says. “That food is the bridge for who we were as a people.”

While a new era is dawning for collard greens, Wallace says that many Americans typically still prepare them the classic way, by stewing them with ham or bacon. “When I was in Jamaica,” she says, “they grew them and ate young collards in salads. There’s ways of eating them that we aren’t accustomed to, like Brazilian-style collards with garlicky flavors. There are so many options.”

Ashleigh Shanti, a chef and board member of the Utopian Seed Project, is also involved in the collard trials. Her role is creating new recipes that show off the versatility of collards, in the hopes that more people will adopt it as a staple. According to her, local cooks have long since started experimenting with the hearty green. “Chefs in the South do really cool things with them,” she says. “Pickling stems, making kimchi, using them like fig leaves to wrap things.”

As the collard green trials continue into 2021, participants will grow and record data about their collard greens, preserving both their seeds and their backstories from oblivion. To Smith, seed and story are inseparable. “We vote every four years but we eat three times a day,” he says. “Our connection to food is power. It’s racial justice, environmental justice.” It only makes sense, he states, to use collards “as a story to talk about these things.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook