Airing Out the Mystery of the Mad Gasser of Mattoon

What a strange spate of “gas attacks” tells us about what was really lurking in mid-century America.

It began on September 1, 1944, in the sleepy community of Mattoon, Illinois, at the home of Aline Kearney and her three-year-old daughter, Dorothy Ellen. Her husband was away, serving in the Navy, and Aline’s sister Martha was staying with her. That evening, Aline noticed a “sickening, sweet odor,” though Martha didn’t report smelling anything unusual. Abruptly, Aline’s legs seemed to become paralyzed, and she felt a tightness and a dryness in her throat.

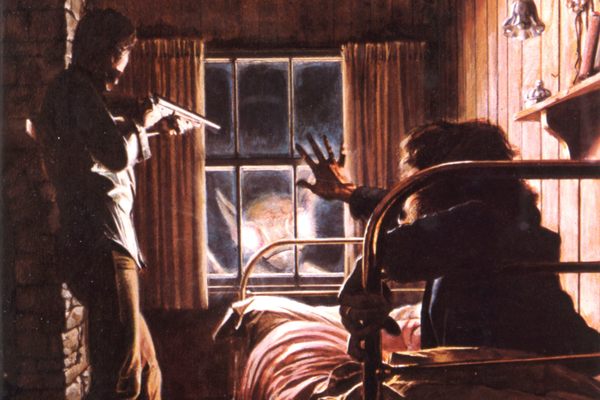

Alarmed, Martha called her husband Burt; when he arrived, he saw a man outside, lurking near a bedroom window. He was tall, wearing dark clothes and a tight-fitting cap. Burt gave chase but was unable to catch him. Aline Kearney’s paralysis, meanwhile, resolved itself within 30 minutes. But this was only the beginning.

The next day, the town’s Daily Journal-Gazette published an article: “Anesthetic Prowler on Loose,” which detailed the Kearney household’s story. Soon other stories began to emerge. Orbon Raef and his wife came forward and reported that the night before the Kearney attack, they’d both been asleep when they were awoken by a strange smell in their bedroom, after which they were paralyzed for almost 90 minutes.

Another woman, Olive Brown, claimed to have been attacked months earlier, with similar symptoms. The wife of George Rider reported an attack the same night as the Kearney incident: She had been up, drinking “several pots of coffee,” when she heard a noise like a “plop,” followed by a strange smell that made her hands and legs tingle and left her feeling dizzy, like she was floating. Another person, unnamed, reported a sickening, sweet smell that caused her children to vomit.

Things grew stranger. A few days later, on September 5, a woman named Beulah Cordes found a small cloth on her front porch. Realizing it was still damp, she picked it up and sniffed it. The smell overwhelmed her—she staggered a few steps, and then screamed. “It was a feeling of paralysis,” she reported, describing it like an electric shock. She was sick for the next two hours, but when the cloth was subjected to chemical analysis, no chemical traces were found. A local fortune teller named Edna James smelled a strange odor in the boarding house she ran and went to investigate; she would later claim to have encountered an “ape-like man with long arms reaching out, holding a spray gun,” who doused her three clouds of gas that caused her arms and legs to go numb.

As the panic in Mattoon continued to grow, the Army brought in chemical weapon experts. The best hypothesis they had was that the chemical agent might have been chloropicrin, a poisonous gas with a sweet odor used for exterminating rodents. But no traces of this gas were ever found, and the reported symptoms didn’t actually match its effects. Meanwhile, armed vigilante gangs began patrolling the streets of Mattoon at night, on the hunt for what had come to be known as the “Mad Gasser.” The police began assembling a list of suspects: Theories included a disgruntled high school chemistry teacher, a violent prankster, or even an escaped Nazi or Japanese prisoner of war. A wealthy eccentric known to have a laboratory in his basement was investigated, and police begin calling mental hospitals to see if any recently released patients had obsessions with poison gas. One woman, loading her husband’s shotgun, accidentally fired it and blew a hole in her kitchen wall. The Chicago Herald-American’s September 11 headline said it all: STATE HUNTS GAS MADMAN.

The mysteries that surround this story are legion, but a few key, bizarre details stick in my mind. For one, the tight-fitting skull cap. Why this strange garment—one that evokes the sightings of Spring-Heeled Jack in London over a century earlier, a figure described as wearing a helmet and a “tight-fitting suit” that looked like “white oil-skin”? Why did Edna James describe her assailant as “ape-like”? And what of this manner of attack—pumping gas into unsuspecting family’s homes?

Since I first learned the story of the Mad Gasser, I’ve always found it distinctly unsettling. It doesn’t elicit a sense of outright terror, per se. It does not feel like a horror movie. Maybe it could have been one, but the attacks stopped without anyone being seriously hurt or killed. There was a real sense of menace, however, a threatening aura, but one without overt violence.

The best name I can give for this feeling is what writer and critic Mark Fisher gave it: eerie. In his 2016 book, The Weird and the Eerie, Fisher describes both sensations as being preoccupied with a “fascination for the outside, for that which lies beyond standard perception, cognition, and experience. This fascination usually involves a certain amount of apprehension, perhaps even dread—but it would be wrong to say the weird and the eerie are necessarily terrifying.”

While he associates the “weird” with a Lovecraftian eruption of the inexplicable into the normal world, “the eerie is fundamentally tied up with questions of agency. What kind of agent is acting here? Is there an agent at all?” It is a sensation, he argues, that is “constituted by a failure of absence or by a failure of presence. The sensation of the eerie occurs either when there is something present where there should be nothing, or if there is nothing present when there should be something.” The story of the Mad Gasser is eerie, perhaps, because it involves a presence where there should be nothing, a figure that goes beyond being merely an intruder. A thief is a common enough sight—the Mad Gasser was someone or something that simply did not belong.

What the eerie troubles, Fisher goes on to suggest, is “the very structures of explanation that previously made sense of the world.” It’s a phrase I’ve come back to more and more as I’ve delved deeper and deeper into the strange history of this land. I was raised to believe America was a place of order, with a trajectory that ultimately bends toward progress. For all of Americans’ faults and missteps, irrationalities and peculiarities, this was a country that I always assumed, on some level, made some kind of sense. There were strange tales, but they were blips, errata, diversions. But the more time I’ve spent in this country, the more I’ve come to see these moments of oddness as central to the American story. The United States, in a word, is eerie.

The story of the Mad Gasser remains unsettling and eerie to me despite the overwhelming consensus as to what really happened in Mattoon. After an obvious culprit could not be found, authorities began looking for alternative explanations. At first, police chief Eugene C. Cole claimed that the gas attacks were not the result of an assailant, but chemical run-off from the nearby Atlas Imperial Diesel Engine Company, which was at that point devoted to producing army shell casings. (Atlas officials rejected this, noting their own employees never noticed fumes or got sick.)

But when one victim’s supposed attack turned out to be nothing more than an accidentally spilled bottle of nail polish, Cole shifted his position. He announced that the whole thing had been mass hysteria—what we now call mass psychogenic illness—from the start. Public officials quickly got on board. Commissioner of Public Health Thomas V. Wright, opined, “Someone is going to get killed and it won’t be from gas. The people here have lost control of themselves in a manner which is almost unbelievable in a modern world. I wouldn’t walk through anyone’s backyard for $10,000.” Sure enough, once the mass hysteria hypothesis took hold among local officials and the media, the actual reports stopped abruptly.

Mattoon became an object of national ridicule. As the Decatur Herald reported, “Our neighbors in Mattoon sniffed their town into newspaper headlines from coast to coast.” Later, sociologists began to use Mattoon as a literal textbook example of mass psychogenic illness—how it spreads and is fueled by fear, carried by neighborhood social vectors, and amplified and given shape by local media. As J.P. Chaplin would write in his 1959 book Rumor, Fear, and the Madness of Crowds, Mattoon “probably represents one of the purest outbreaks of mass hysteria on record.”

It would not be the last. Another example: In 1972, workers at a midwestern university’s data center began to complain that they had been victims of some sort of gas attack. They had been exposed, they claimed, to some mysterious gas from an unknown source, one that caused dizziness, fainting, nausea, and vomiting. At least 10 workers were treated for their symptoms, and the data center was evacuated. Despite repeated tests, no physical cause for the cluster of symptoms could be found.

Sociologists studying the event proposed a different explanation. The workers were socially isolated from each other, unable to communicate except during short breaks. They were forced to wear an unpopular uniform, and were under constant supervision. Perhaps most significantly, a new construction project next door was creating a great amount of noise. Researchers found that the frequency and severity of symptoms were tied to individuals’ personal job satisfaction levels, and that coworkers who interacted socially shared similar levels of both. Researchers Sidney M. Stahl and Morty Lebedun concluded that those less “psychologically sophisticated” are more prone to “to somatize or convert their psychological problems into physical disorder.” Mass psychogenic illness, it seems, is perhaps the result of the “wrong” kind of people having the right kind of reactions to stressful or unsustainable situations.

The people of Mattoon, too, psychologically sophisticated or not, were under a great deal of stress. Most sociologists and historians point to wartime exhaustion—the community had endured wartime deprivations for years, with many of its male population absent and at grave risk overseas—and constant fears that the Germans or Japanese might begin using chemical weapons, as reasons why the people of Mattoon may have converted normal symptoms such as headaches, dizziness, and fatigue into stories of a malevolent intruder.

But this was true of much of the country at the time. Something set off the people of Mattoon, who, through a feedback loop of neighborhood reports and newspaper articles, manifested a phantom. And in turn the rest of the country became fascinated by what happened in Mattoon because it gathered the same fears the whole nation was experiencing, literalized them in an eerie lurker. And then when the cause was revealed to be fictional, it was as though Mattoon allowed the whole nation to expiate it anxiety and exhaustion brought on by the war.

The people of Mattoon envisioned a figure who didn’t just menace them, but whose methods and motives remained elusive—a distinctly amorphous presence that also gave shape to their inchoate anxieties. What Mattoon seems to suggest is that sometimes, when presented with an untenable reality, we respond by making the landscape itself eerie.

A curious postscript of sorts: This would not be the last instance of a strange intruder gassing individuals. Decades later, the city of Springfield, Missouri, became the scene of a strange series of events. In summer 1987, a man the police dubbed “Ether Eddie” broke into 15 homes and used a cloth soaked with some kind of chemical—perhaps formaldehyde—to subdue a number of women, ranging in age from 8 to 56. Bizarrely, the intruder never attempted to steal anything of value, and never committed sexual assault or any other kind of violence beyond the chemical attacks themselves. As Dave Bowden, one of the detectives working the case, told the media, “He’s getting something out of it, at least in his own mind. We just don’t know what it is.”

After a several-month absence, the bizarre attacks began again the following year. The hysteria built, with residents rushing to install deadbolts on doors and bars on windows, refusing to go out at night, and exhorting their teenage daughters to do the same. Finally, on Friday, August 28, 1988, a woman heard a noise outside her window and found a man, Gary Ray Curtis, trying to pry open a window with a screwdriver. She shot him through the glass, wounding but not killing him. Despite repeated attempts, the police were never able to connect Curtis to the Ether Eddie incidents, let alone divine some kind of motive for the bizarre incidents. Curtis was subsequently sentenced to 10 years solely for the attempted burglary. And though the gas attacks ceased after Curtis’s conviction, they remained officially unsolved.

Colin Dickey is the author of five books of nonfiction, including Ghostland: An American History in Haunted Places, and, most recently, Under the Eye of Power: How Fear of Secret Societies Shapes American Democracy. He also hosts Atlas Obscura’s Monster of the Month.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook