How Corning, New York, Changed the World With Glass

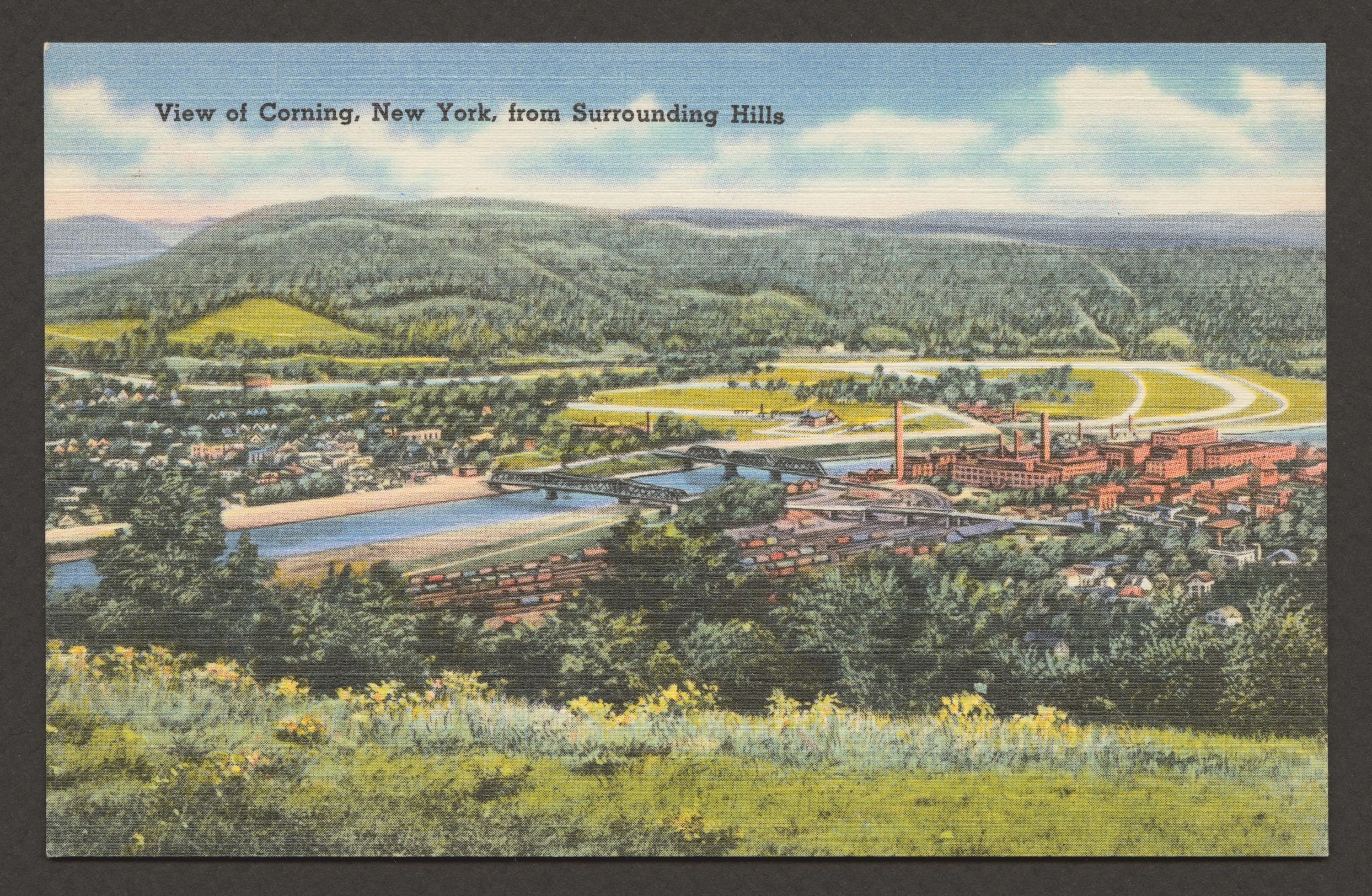

In the late 1860s, a barge helped the “Crystal City” usher in a new era of innovation.

In 1868, just three years after the conclusion of the American Civil War, a barge set off from Brooklyn, New York. Loaded with equipment and supplies, it was bound, via New York’s extensive waterways, for the upstate town of Corning. Few could have predicted the way the vessel and its contents were about to change the world.

The barge’s mission was the relocation of the Brooklyn Flint Glass Company, which would soon be renamed Corning Glass Works. Corning was a transportation center for canal and railway networks that provided easy, relatively cheap access to the resources necessary for glass production. The Houghton family, which owned the company, had already forged a relationship with Elias B. Hungerford, a Corning businessman with a patent for glass window blinds, and so they decided to pack the company up and send it on a journey up the newly enlarged Erie Canal.

The move came at a fortuitous time: in the wake of the war, America was changing rapidly, and demand for glass was high. Among the trends driving this demand was a hunger for luxury goods, including elaborately detailed lead glass tableware known as brilliant cut glass. With Corning quickly establishing itself as an important center for glassmaking, the town, and its surrounding areas, began to attract an influx of skilled glass cutters and artisans from around the world. Before long, Corning Glass Works was no longer the only glass game in town. Dozens of glass cutting firms, including the famed T.G. Hawkes & Co., established themselves in the area, leading Corning to be dubbed “The Crystal City.”

While Corning was becoming famous for the detail and artistry of its decorative glass exports, the city’s glassmakers were also quietly driving much of the technology that would define the next century. Thomas Edison may have invented the lightbulb, but if not for the innovations happening in Corning, it may never have had a chance to take hold.

When Edison first commissioned Corning Glass to manufacture light bulbs, in the early 1880s, the means to produce them was limited. Skilled glassblowers had to make each one by hand, at a rate of only two per minute. It wasn’t until the 1921 invention of the Corning Ribbon Machine, by William J. Woods and David E. Gray, that this would change. In just a few years, the new machine was able to pump out 300 lightbulbs in the same amount of time it had previously taken to produce just two. Suddenly, light bulbs were cheap and accessible enough for widespread use. The world lit up.

This would prove to be only the beginning of the many technological advances coming out of Corning. Some of these technologies are now so woven into our everyday lives that it’s easy to forget how innovative they were in the first place. After all, who doesn’t have a Pyrex measuring cup, or a set of heat-resistant Pyrex dishes? In fact, the glass used in these dishes is a temperature-resistant borosilicate glass first developed in Corning for use in railroad lantern globes.

Other advances were more dramatic, if less culturally iconic. Glass techniques developed in Corning in the 1930s are still used to create the giant reflective lenses in telescopes that allow us to see into the far reaches of space. And without the fused silica used in fiber optic cables, the internet as we know it likely wouldn’t exist.

The story of Corning isn’t just a story about glass. It’s about the roiling cycle of progress, with small changes leading to big ones, all reliant on the confluence of artistry, craftsmanship, and scientific innovation. It’s about how elaborate, carefully crafted wine goblets led to mass-produced light bulbs, and how one city became the center of it all.

This summer, to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the relocation of the Brooklyn Flint Glass Company—now known as Corning Incorporated—The Corning Museum of Glass will send GlassBarge on a four-month expedition via New York’s waterways. GlassBarge will offer glassblowing demonstrations daily from 11 a.m. to 5 p.m., every hour on the hour. Visit www.cmog.org/glassbarge for schedule information and to register for free tickets.

This post is promoted in partnership with The Corning Museum of Glass. Click here to discover more.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook