The Race to Document Prehistoric Art in a Coastal Cave in France

Scores of ancient paintings and other works will soon succumb to the sea—but a passionate team is determined to preserve this ‘bubble of memory.’

When prehistoric artists entered the narrow first passageway of what’s now Cosquer Cave some 27,000 years ago, they moved from flat, grassy plains up a small incline to the base of a cliff a few miles from the sea. Today, when Bertrand Chazaly enters the French cave to digitally scan the paintings and engravings those artists created, he has a tougher journey.

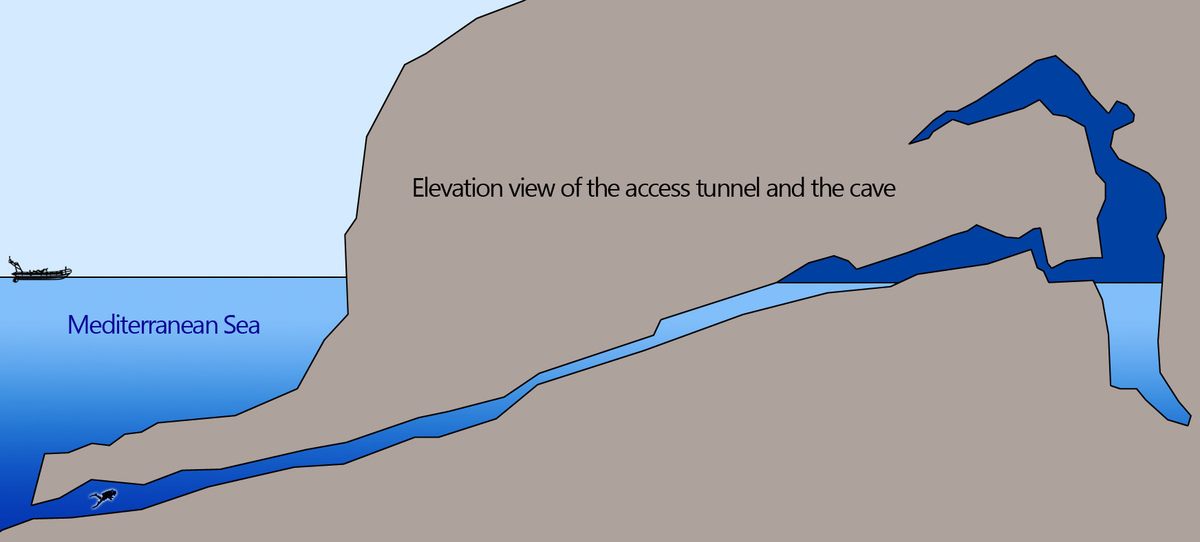

Higher sea levels since the last ice age have left the cave’s mouth more than 120 feet underwater, and submerged the tunnel, which is longer than a football field. But at its end are two chambers that are at least partially dry—for now.

Cosquer Cave contains a trove of prehistoric art, but its inaccessibility makes it difficult to study. And the clock is ticking: Encroaching sea levels are washing away paintings and engravings. The 3D digital models Chazaly’s team produces will preserve the site virtually, but collecting data takes technical innovation and physical stamina.

“It’s really hard,” says Chazaly, a land surveying engineer who specializes in caving and cultural heritage for geo-data company Fugro. Over the last 12 years, he has worked several weeks each year in the cave. “It’s really a question of passion.”

This year, Chazaly’s team finished mapping the portions of the cave that are above water, using laser scanning and photogrammetry to create models accurate to within 0.1 mm. Next, they’ll document what’s underwater. Though no art survives on the submerged walls, a complete model of the cave system will help researchers understand how it was used in prehistory.

The cave’s remaining art, dated to between 19,000 and 27,000 years ago, includes hand stencils by men, women, and children, and scores of animal figures: bison, horses, ibex, and chamois, as well as seals and seabirds.

Prehistorian Jean Clottes was working at the French Ministry of Culture in 1991 when diver Henri Cosquer reported a cave he had discovered a few years earlier on the rocky coast east of Marseille. Cosquer’s photos intrigued Clottes, but he couldn’t see it for himself—he wasn’t a diver. Even now, it takes a particular skill set, combining expertise in both cave art and cave diving, to study Cosquer in person. “There are not too many people who can do that,” Clottes says.

Clottes eventually became one of those people, learning to dive at age 69, just so he could study Cosquer Cave. He’s made dozens of visits and, once he reaches the cave’s dry chambers, says his work is similar to other prehistoric sites. But just getting to the cave can be complicated; rough seas and bad weather often cancel outings.

Cosquer presented unique challenges even for Chazaly, who has worked in some extreme places, including the spire of Mont-Saint-Michel, 450 meters underground in nuclear waste storage galleries, and the Great Hypostyle Hall of Egypt’s Karnak Temple. When the French Ministry of Culture first contacted him more than a decade ago about the possibility of creating a digital model of Cosquer Cave, Chazaly first needed to improve his diving skills, from leisure to professional level. It then took several years of test visits before his team could begin to scan the cave in 2017.

Each scanning trip involves one or two researchers accompanied by two expert divers who are familiar with the cave. From a boat off the rocky coast of Calanques National Park, they descend into turquoise Mediterranean waters, carrying equipment in sealed bags and a key to unlock the gate at the tunnel’s entrance.

With one diver at the front and one at the back, they swim slowly, careful not to kick the sediment on the floor which, if disturbed, dangerously clouds the water. In 1991, three divers died after becoming disoriented by sediment swirling through the passageway. Now, a lifeline extends the tunnel’s length.

After about 15 minutes, the group climbs onto la plage, the beach, where they leave their diving gear to work above water level on slippery floors amid stalagmites and stalactites. No matter the season, Chazaly says, the temperature is always about 64 degrees Fahrenheit.

Inside, there are strict rules. They must not touch the fragile walls. The only sustenance allowed is water. During their hours-long stay, they can’t snack. They can’t pee. “You really have to be prepared,” says Chazaly. “Sometimes you are really in a hurry to get out of the cave.”

Chazaly’s team customized a laser scanner for the cave’s low-light, remote setting. While the scanner records 70 million points in three minutes, positioning the device—and the humans—took a lot of time. During each scan, the team hid so they wouldn’t appear in the data. At times, colleagues physically held Chazaly on a precarious spot of dry ground. Sometimes he stood chest deep in water with the device on a tripod. Twice, scanners fell into the water and were destroyed.

While scanning every dry cranny of the cave, the lights illuminated new details. Chazaly recalls one time when an archaeologist with the team exclaimed, “Look here, there is a small horse!”

“Nearly 30 years after the discovery, just finding a new engraving or something is quite strange,” he says, “but it happened.”

This year, when Chazaly’s team begins documenting submerged parts of the cave, including some never before explored, there will be new challenges. Divers will spend longer periods of time underwater, which involves greater physical risk. The team will need to move diving gear through a narrow passage between chambers rather than leaving it at the water’s edge, all without touching the easily-damaged walls. To document the long tunnel entrance, where it is not possible to stop because of the risk of disturbing the sediment, Chazaly’s team has designed a ring-like array of cameras and lights that will record 360-degree images along the way.

Scientists familiar with the site see great value in a digital replica of the cave, “a bubble of memory lost under the sea,” according to geologist and prehistorian Jacques Collina-Girard, who says his visits to the cave in the 1990s felt like an H.G. Wells or Arthur Conan Doyle adventure. Already, the above-water scans have been used to construct a replica of the cave for Marseille’s new Cosquer Méditerranée museum. The digital model, Collina-Girard says, makes the cave accessible to the public and to researchers from afar, and preserves what the sea will soon claim.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook