The Dying Art of Courtroom Illustration

Why there are no new artists in the gallery.

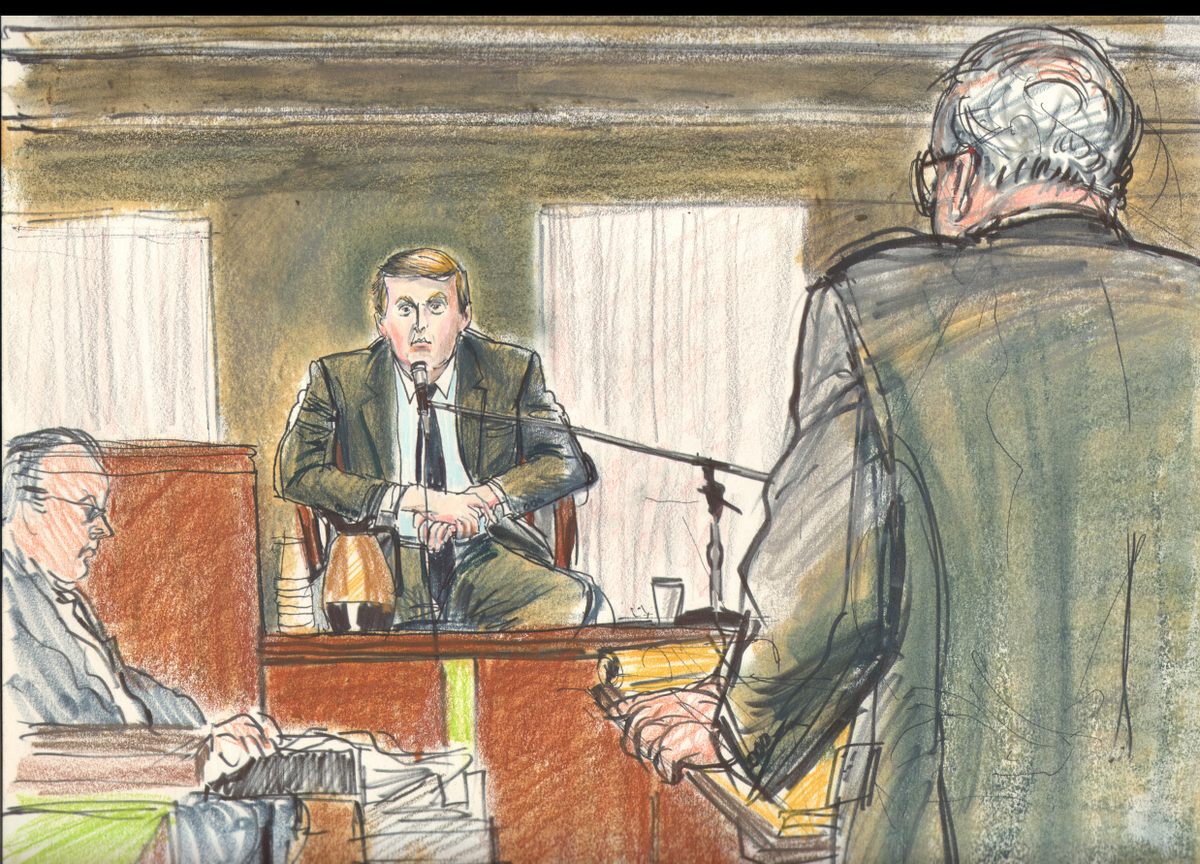

On a recent gray August Monday at the Brooklyn Federal Courthouse, illustrator Jane Rosenberg found herself craning her neck and scrabbling for her pastels. The infamous Mexican drug lord Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán was making his first public appearance in months, and it was Rosenberg’s job to capture the scene for Reuters. Seated next to her, with a brush pen and colored pencils, fellow courtroom artist Elizabeth Williams was also trying to capture his likeness, for the Wall Street Journal.

The artists had been waiting outside the door of the courtroom since 7:30 a.m., long before it opened, to get the best possible seats. When they finally made it inside, El Chapo was present for just 15 minutes. Williams finished one drawing; Rosenberg “very loosely” started two.

“He walked in the courtroom and looked over at his wife and children, and waved,” Rosenberg says. “Then he sat down in the chair by his lawyer, and stood up, started making arguments.” She sketched furiously to complete the drawings later, without any visual reference. “I couldn’t remember if he had on the same color bottoms as his top,” she says. Someone else in the courtroom later confirmed that he had.

Rosenberg is a self-proclaimed “dinosaur,” one of the last courtroom artists working today. Both she and Williams began working in the profession in 1980. Over nearly 40 years, Rosenberg has sketched a veritable who’s-who of celebrity courtroom drama: Woody Allen, Bill Cosby, Martha Stewart, Tom Brady.

Courtroom art has been a feature of the American media landscape since just after the high-profile Charles Lindbergh case in 1935. The famous aviator’s infant son was kidnapped and murdered, and news audiences were insatiable in their demand for more coverage. The media, in turn, went from reportage to circus to full-on hullabaloo. Newsreels of courtroom action, filmed from secret cameras in the New Jersey courtroom, were sent to movie theaters across the country. And so, when the trial was over, the American Bar Association banned cameras from courtrooms altogether. (To this day, they’re not allowed in federal court, though that may soon change.)

Illustrators stepped in to fill the gap, but, by 1980, many states had lifted the photography ban in their courts. A total of 47 states today now allow broadcast coverage of some, if not all, judicial proceedings. “The proliferation of cable television, the advent of the Internet, and the waning economy have combined to greatly shrink the market for courtroom art,” writes Phoebe Hoban in ARTnews.

Detailed, illustrative drawings of courtrooms date back at least as far as the 17th century. Each often serves as a guide to the court standards and mores of the place and time in which it was made. Honoré Daumier, a French caricaturist and artist working in the 19th century, is known for his own courtroom images, which depict nameless lawyers and other judicial workers deep in conversation, peaky faces looming out over dark robes.

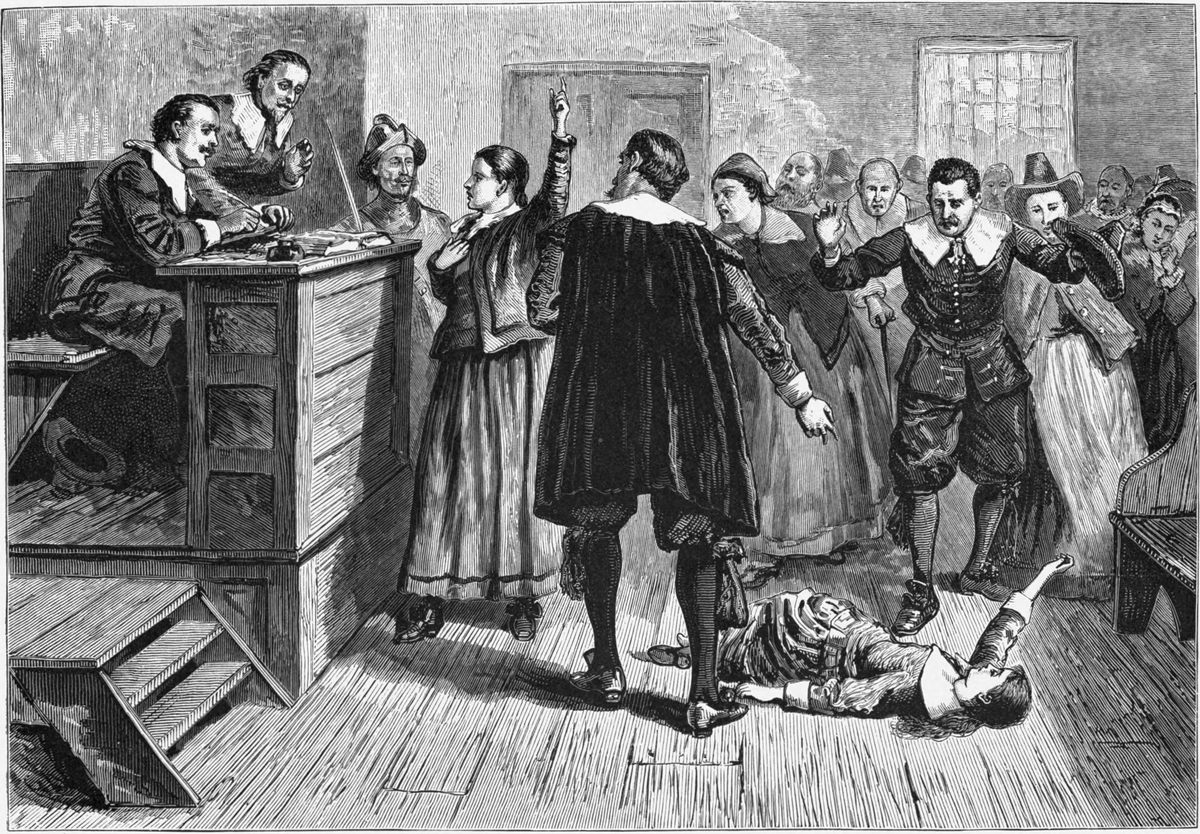

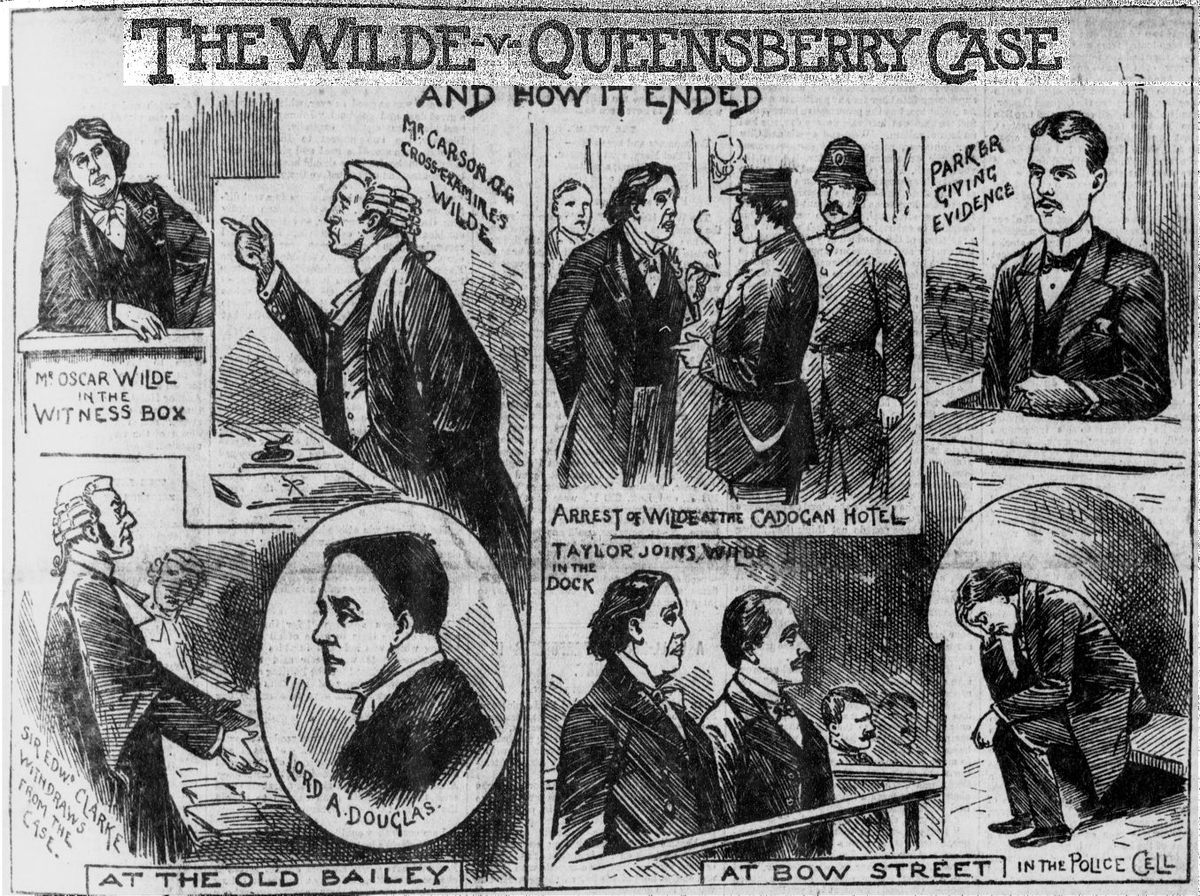

At some point in the 19th century, illustrations started to depict particular court cases. Some were imagined rather than observed. There are, for example, a wealth of dramatic illustrations from this period of the Salem witch trials (around 180 years in the past, by then), showing young women writhing on the floor as townspeople in the background huff and simmer. Others were more journalistic. The Victorian weekly tabloid Illustrated Police News made heavy use of illustrations of definitive moments in contemporary trials, though journalistic conventions of the time meant that these were usually not credited to any one artist.

For Oscar Wilde’s famous 1895 trial for “gross indecency,” for instance, the paper ran a series of illustrations of Wilde and other key players in the courtroom. This practice, however, came to a stop in Britain in 1925, with the Criminal Justice Act, which is still in effect. Among other things, it prohibits taking photographs or sketching anyone in the room, whether “a judge of the court or a juror or a witness in or a party to any proceedings before the court.”

There was concern at the time that photographers or artists might wig out lawyers or defendants, and therefore obstruct the path of justice. Unobtrusive fixed cameras have since been installed, but there’s still a demand for further depictions of certain cases. So British court artists circumvent the law by taking feverish notes about everything they observe—from posture to personal grooming to the color of someone’s tie—and then prepare their sketches outside of the courtroom. Court artist Priscilla Coleman became the first person to be given permission to draw in a courtroom in the United Kingdom in nearly 90 years, at an appeal hearing at the Supreme Court in 2013. At the time, a spokesperson from the court told the Evening Standard that while ordinarily photographers still weren’t permitted in the court, Coleman had been as noninvasive as the fixed cameras.

The golden age of real-time courtroom art in the United States began with Leo Hershfield, hired by NBC to sketch the congressional censure of Joseph McCarthy in 1954. He was rapidly ejected, allegedly, for “behaving like a camera.” After that, illustrators were obliged to work from the same kind of fastidious notes as their British counterparts, until 1963 protests, led by courtroom art “grande dame” Ida Libby Dengrove, “freed them to work on the spot.” That same year, TV news expanded from 15 minutes to a full half-hour, sending demand for courtroom sketches sky-high, as news editors struggled to fill the extra time. One high-profile case followed another: the assassinations of John F. Kennedy, Martin Luther King Jr., and John Lennon, for example. Illustrations were more in demand than ever before, and a new vanguard of illustrators, including former war artist Howard Brodie, went marching into the country’s courts.

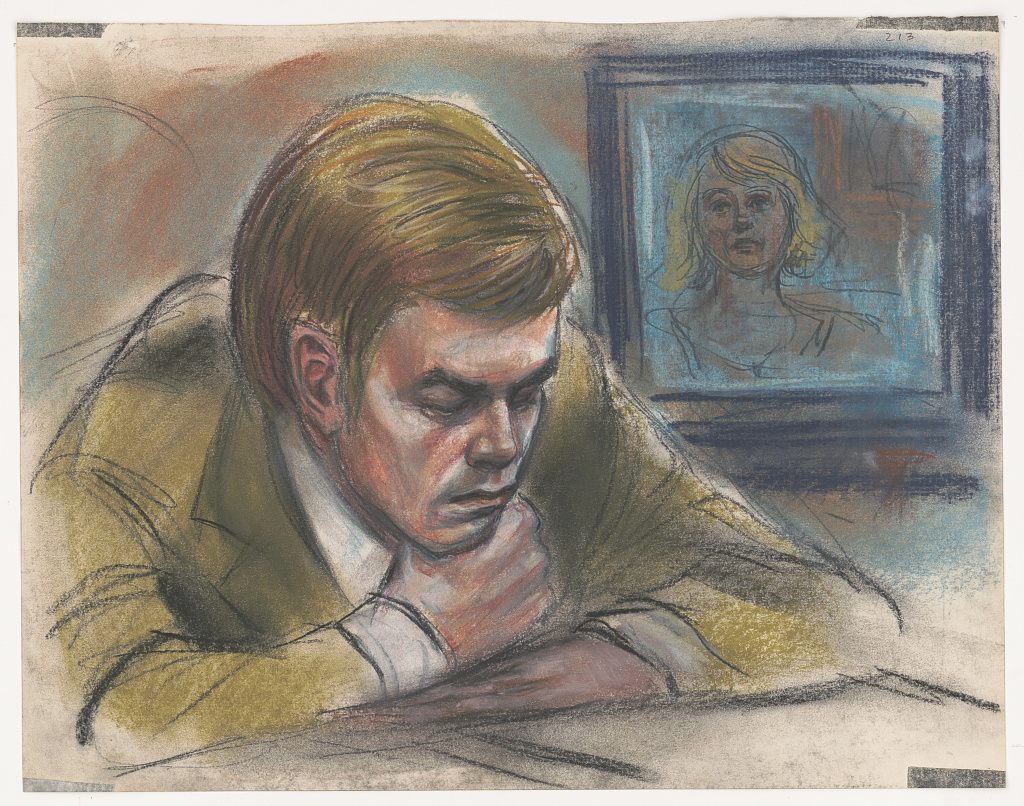

The cases from these years that the artists love best are not always those that the public remembers. Rosenberg fondly recalls the trial of the wine counterfeiter Rudy Kurniawan. “I loved drawing all those bottles of wine, because they laid them out as evidence,” she says. “It was so much fun—like being back at art school.” And for Williams, a particular favorite was the cocaine-trafficking trial of automaker John DeLorean trial in 1984. She had a fantastic vantage point, she says, loved drawing former model Cristina Ferrare’s “fabulous clothes,” and enjoyed the support of encouraging, more seasoned colleagues. At that time, court illustrators were commonly sent along with reporters, who would tell them what to look out for. These days, they mostly work alone and hope they manage to capture what their client news organizations want.

Photographs might seem a better method for capturing an accurate likeness, but courtroom sketches provide something extra, something about the emotional resonance of what happened, Rosenberg says. “It can provide more of an essence.” Williams remembers seeing a heavily cropped photograph from a trial that failed to show how a 6-foot-5-inch, 300-pound defendant dwarfed his attorney. “And that’s a very important part of what that scene was,” she adds. On top of that, a photograph might capture someone between expressions, or with a fleeting grimace that doesn’t necessarily characterize the overall emotional tenor of a courtroom situation or moment.

All courtroom illustrations are necessarily impressionistic in this way, writes Katherine Krubb, who curated the 1995 exhibition Witness of the People: Courtroom Art in the Electronic Age at what was then called the Museum of Television and Radio in New York (now the Paley Center for Media). “[They] seek to capture scenes from everyday modern life in flickering, fleeting images,” she writes, comparing them to the work of 19th-century artists Edgar Degas or Édouard Manet. “The pursuit of verisimilitude leads to exaggerations and distortions.” There tends not to be much physical action in a courtroom: Instead, artists must rely on minute changes of facial expression to communicate the drama of the proceedings.

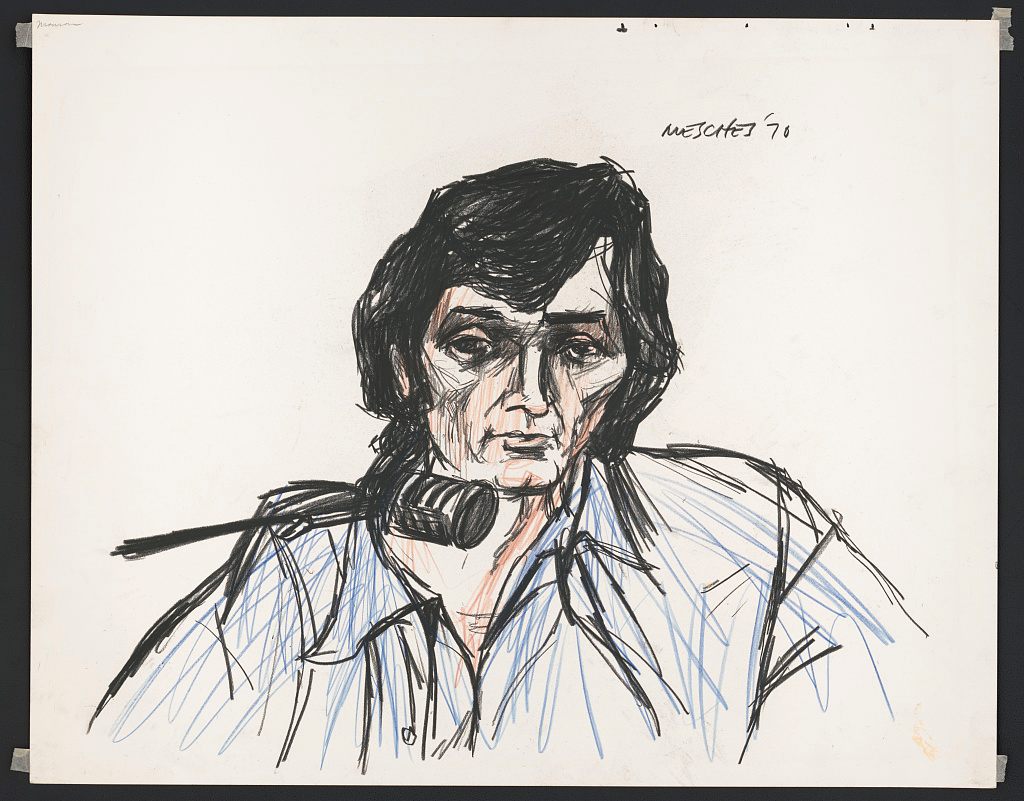

Rare moments of action often reap some of the most famous courtroom images: Bill Robles’s 1970 drawing of Charles Manson leaping from the defense table, intent on stabbing Justice Charles H. Older with a pencil, for instance. (Manson is mostly a frenzied scribble, his pencil soaring toward the judge.) “That was my first trial,” Robles recollects. “I’d never set foot in a courtroom before.” Williams remembers catching what she later described as “a great moment,” rather than “a great drawing,” when she drew notorious fraudster Bernard Madoff cuffed and being led away by officers.

Increasingly, the few remaining court artists are expected to do this thoroughly analog job in a digital world, where technology affects everything—from the challenges of creating these images to their public reception. In court, Rosenberg “wriggles around” to get the best view she can amid a forest of computer screens. Immediately afterward, she must photograph and email her work to a television studio, where it features on news broadcasts.

On top of that, illustrators are at the mercy of thousands, if not millions, of internet hot takes on their work. Rosenberg, for example, went viral after one of her sketches of Brady, quarterback on the New England Patriots, caught the world’s attention in August 2015. It was variously labeled “troll-faced,” “haunting,” and like it was “put in one of those machines that crushes cars.” Rosenberg found herself the victim of the opprobrium of vicious football superfans. “I got a lot of negative bullying on the internet,” she recalls. “A lot of that was from rabid Patriots fans. I didn’t know about that world, but I’m learning about it.” More recently, Taylor Swift’s sexual assault case made headlines not just for its outcome, but for sketch artist Jeff Kandyba’s perceived failure to capture the pop star’s likeness.

This artist’s rendition of Taylor Swift is a very good sketch of Rolf from The Sound of Music. pic.twitter.com/Qf37v3J8vC

— Anne T. Donahue (@annetdonahue) August 9, 2017

And now the days of courtroom illustration may be numbered. “It’s a matter of time,” says Williams. “I always thought it was.” In March of this year, senators Amy Klobuchar and Chuck Grassley introduced bipartisan legislation that would finally allow cameras back in federal courtrooms. If it passes, this could be the final nail in a coffin that’s already almost sealed. “That’s pretty much going to do it in,” Williams says, a little wistfully.

Robles is more circumspect. “They’ve had cameras for years, but a lot of the judges—the TV stations petition the court to allow a camera in, and they deny them that right. So that’s where we come in.” Judges famously banned cameras at Lindsay Lohan’s 2011 trial, for instance. Robles is currently preparing for the forthcoming murder trial of real estate scion Robert A. Durst. Though they may be a costlier option for media companies than using photographers, “we’re a necessary evil,” he says. “When there’s no cameras permitted, we’re king.”

Today, illustrators might work just 100 days in a good year, says Robles, and usually only for extremely high-profile cases. “People probably think it’s a piece of cake,” he adds. But key players are moving around the courtroom all the time, refusing to pose, and sometimes hiding their faces between newspapers or their hands. “But sooner or later, the judge will make them uncover their face,” he says. “So you get them one way or another. They never escape.”

It’s a hard, insecure job, Williams says. “Sometimes you can sit there and struggle. You can never, ever sit back and say, ‘Oh, this is going to be a breeze.’” She adds, more seriously, “This business will destroy you, if you think that. It will chew you up and spit you out. It is a tough business, and it takes nerves of steel to do it. I’ve seen artists just fold up and—‘Forget it, no,’” she says. Robles too has observed fellow illustrators running out of the courtroom when confronted with “death pictures and mutilations and so forth.” Today there’s barely enough available work for experienced artists, and no space for new ones.

On top of that, it can be very stressful. “But I’ve been doing it so long, it’s routine. A novice, I think, would be paralyzed.” It’s occasionally a struggle not to take the emotions of the trials home with her, says Rosenberg. “Sometimes it affects me, sometimes I cover horrific trials which make me cry.” But, somehow, this, and the punishingly early starts, don’t diminish her enthusiasm for the job. “I love it still,” she says. “I was telling my husband the other day, if I won the lottery, I would still do it—but I’d pay a sherpa to carry all my supplies for me, so I just had to show up.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook