Curiouser and Curiouser: The World’s Most Unusual and Beautiful Maps

The Lion of Holland, from 1609, by Claes Jansz Visscher. (All images The British Library Board/Courtesy The University of Chicago Press)

Even though without them we’d be lost, laypeople often take maps for granted. And, really, who can blame us? Rand McNally editions get mashed up in backseats and directions magically appear on screens. The maps most of us interact with don’t have much flair. But our blasé attitude is undeserved. Over the years mapmakers have blurred the lines between art and cartography, crafting strange, funny and surprising works.

In The Curious Map Book, co-published this year by the British Library and The University of Chicago Press, London-based map dealer and researcher Ashley Baynton-Williams presents a treasure trove of such cartographical wonders. Largely culled from the British Library’s vast collection, there are maps shaped like winged horses and lions; maps on teacups and blankets. Far from merely relics, Baynton-Williams includes examples from the present day.

Baynton-Williams answered questions about the book over email.

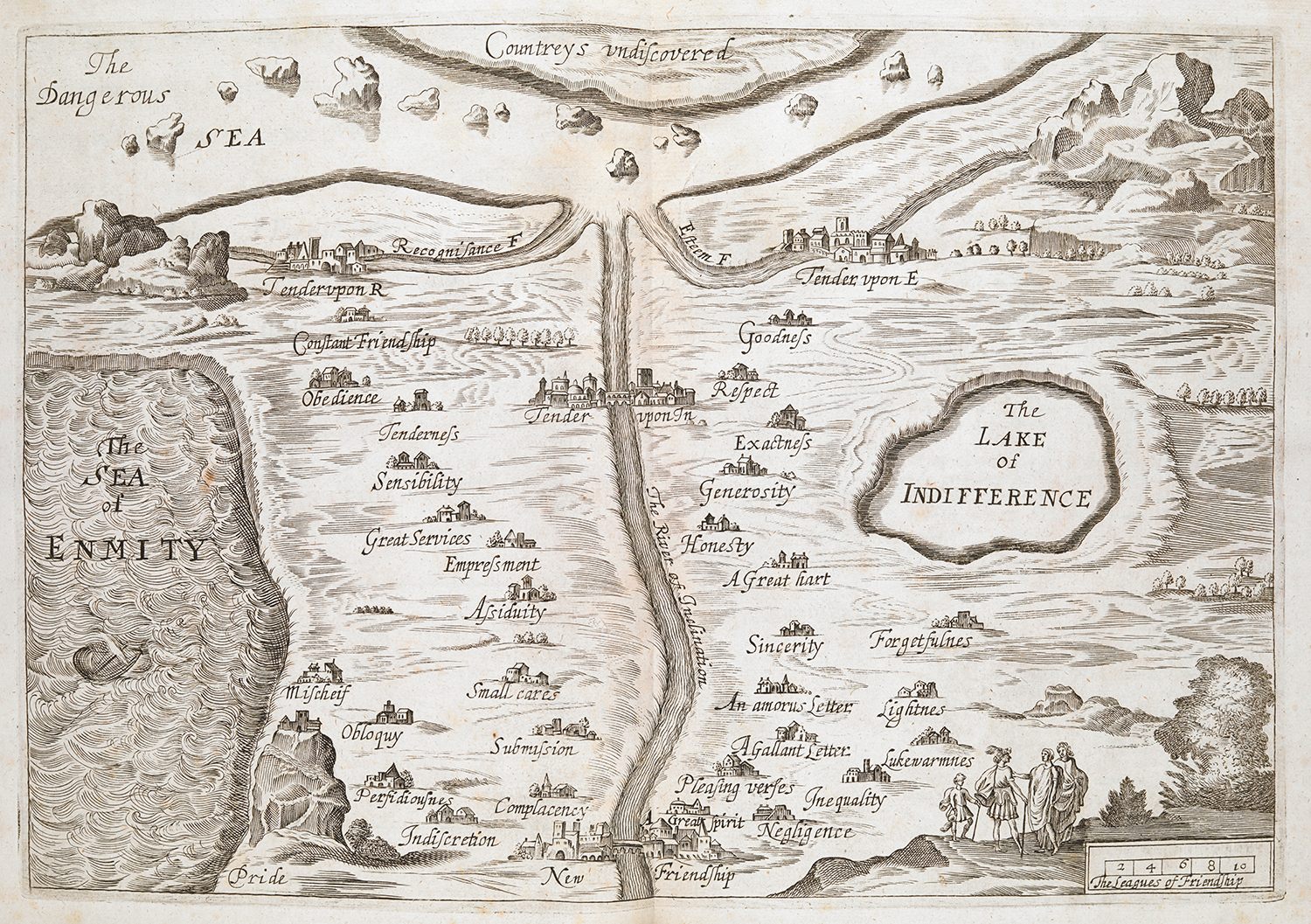

A 1655 untitled map of the ‘Land of Tenderness’, by Madeleine de Scudery, London.

What makes an antique map unique and remarkable, or sets it apart from other antique maps?

The vast majority of antique maps are actually simply copies of existing material. The publishers were unable to afford their own surveys - we’re in the days well before satellite photography—and geographical advances were a slow process, so they simply copied an existing map, disguising the fact by changing the decorative features.

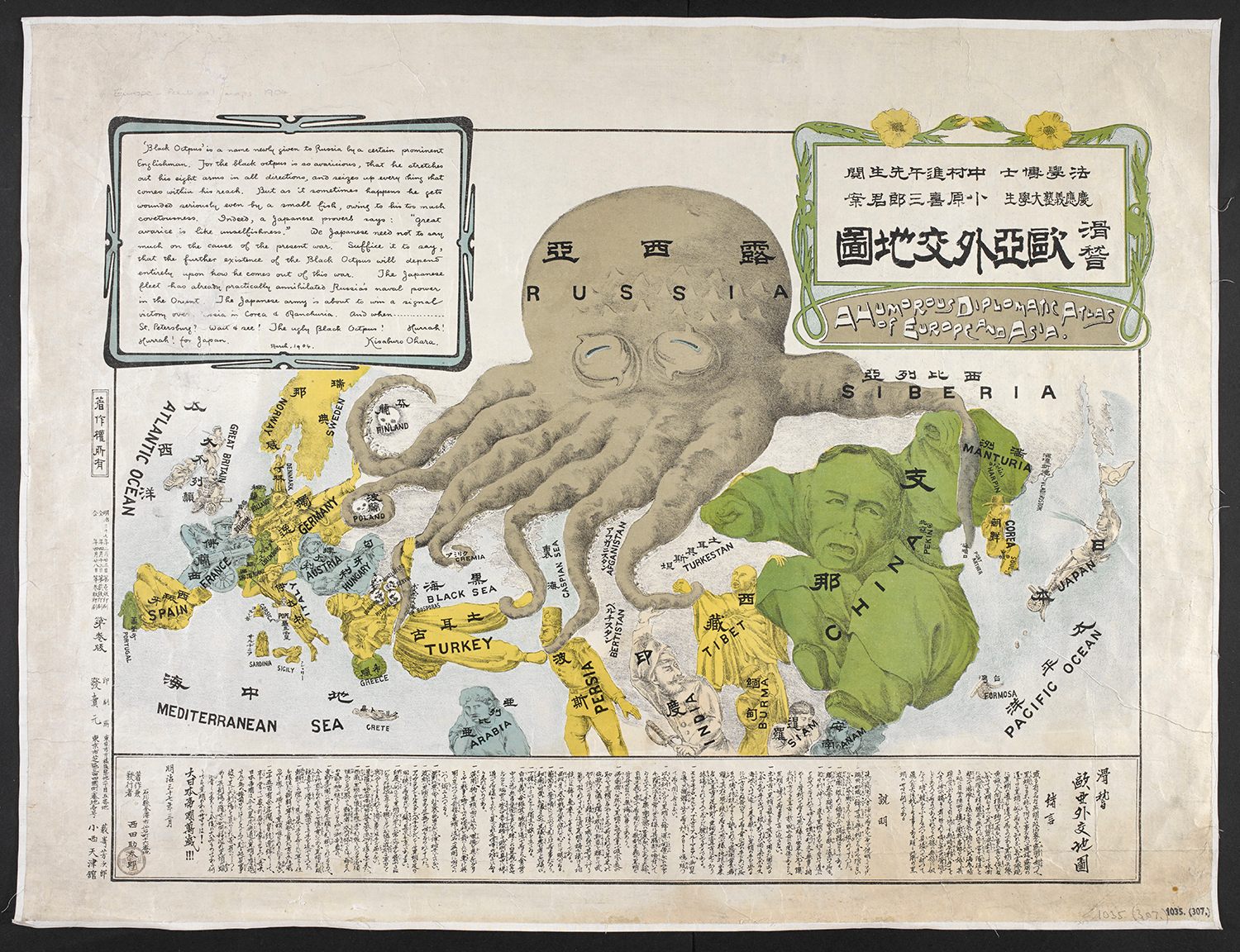

‘A Humorous Diplomatic Atlas of Europe and Asia’, 1904, by Kisaburo Ohara, Tokyo.

What sets these curious maps apart (with the exception of the “Leo” maps of the Low Countries and a couple of others that caught mainstream attention) is that they represent the individual (unique) artistic talent of the maker, who created the image—and the range of items illustrated in the book is limited only by that imagination.

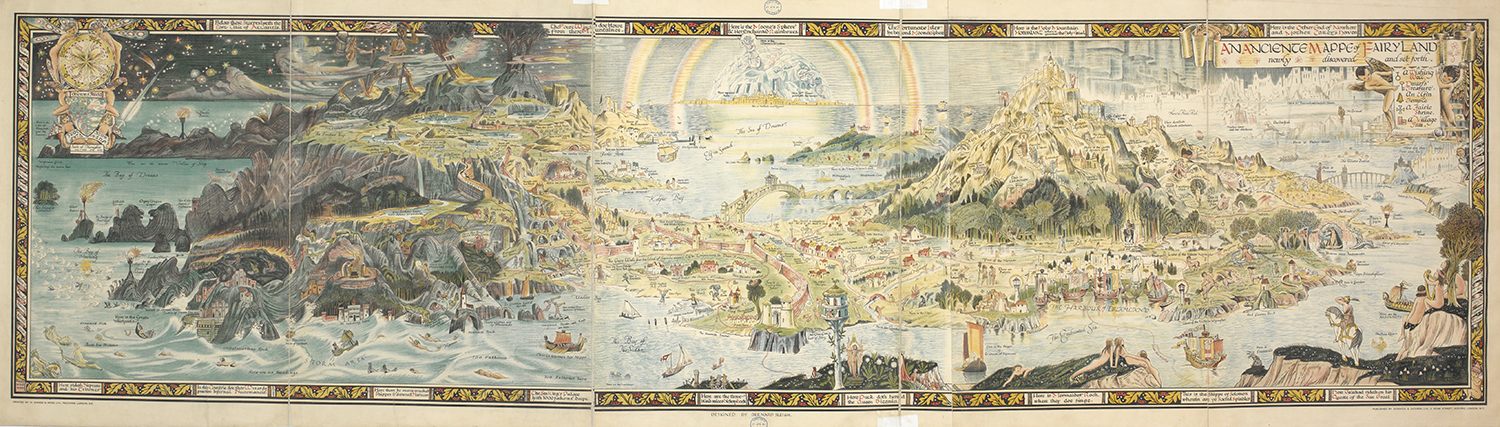

The Sleigh Fairyland Map is one item that I could simply look at for days and see different little elements. It’s an amazing map—and design.

‘Geography Bewitched! Or, a Droll Caricature Map of Scotland’, by Robert Dighton Sr 1793.

How did you come to be interested in maps and what continues to fascinate you? How has the field of map study changed since you first started?

I was lucky; my grandfather and father both dealt in maps and prints. I was surrounded by them from an early age and loved it. I think I knew my career path from about 11 and I’ve never regretted it. Every day is different; almost every day I see something new, and pretty much every day I find out how little I really know. It’s a bit humbling, but I love the idea that forty years in I’m still on an upward learning curve.

How has study changed? There are two ways; the first is the internet; I’m not sure I recommend the internet for the written word, but the availability of images is a huge help to researchers and writers like me. The American libraries have led the way in the digitisation of map images; the Library of Congress, the John Carter Brown Library, Yale, Harvard, the American Antiquarian Society and the Boston Public Library and the collector David Rumsey out in California (to name sites I use regularly) are making available amazing quality images that are freely downloadable. What previously might well have been days or hours of travel converted into minutes of download time.

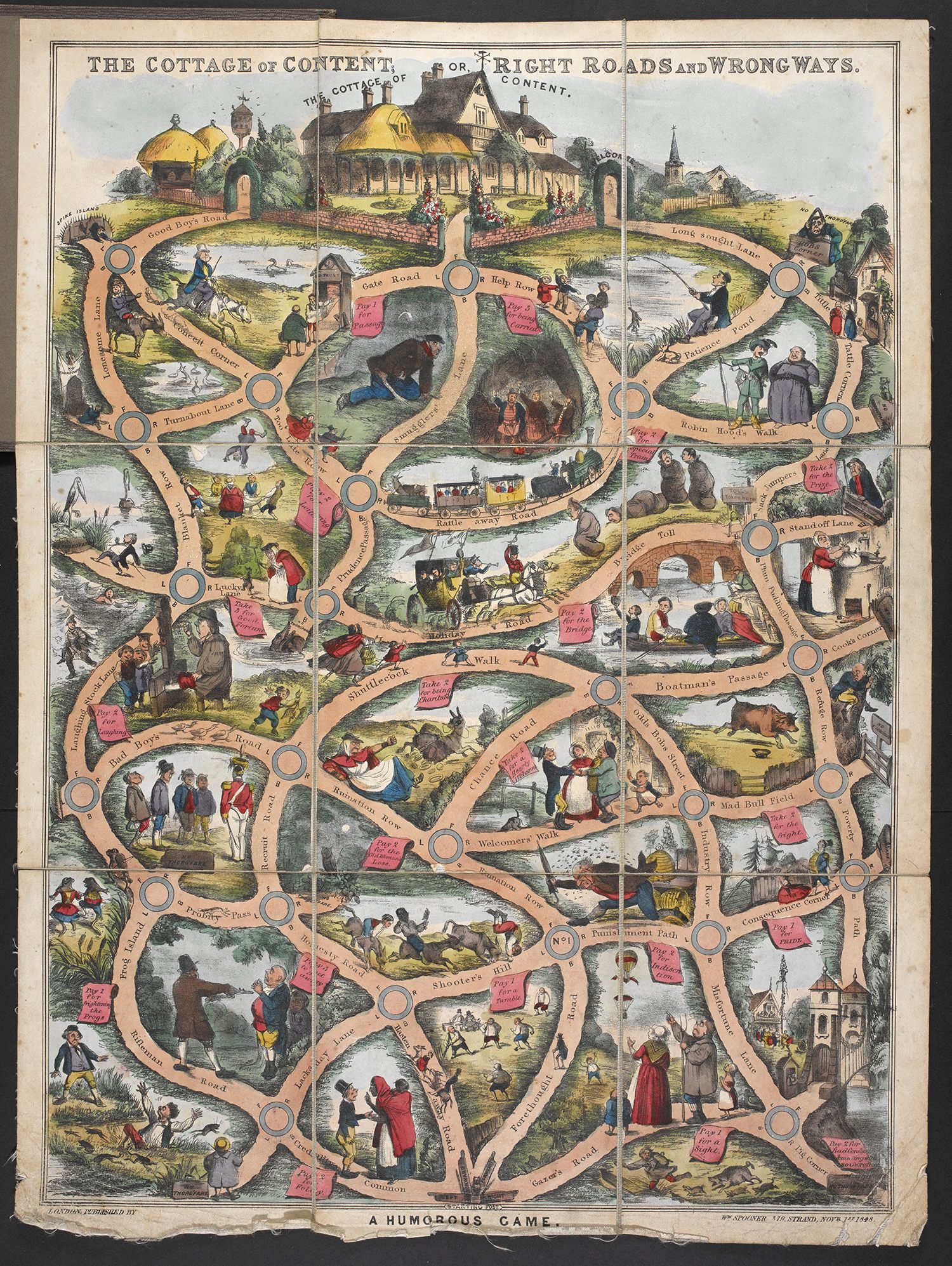

William Matthias Spooner’s ‘The Cottage of Content or Right Road and Wrong Ways. A Humorous Game’, 1848.

The other way that study has changed is that it has become more academic; the great reference books from the past were about the maps themselves and the way the information they showed changed.

More recently (relatively speaking) the focus became more about the underlying philosophy / symbolism in the map, and the intent of the maker, begun by the late, great, J.B. Harley, who was founding editor, with David Woodward, of The History of Cartography project. While I think there is a valid argument—demonstrated, for example by Peter Barber and Tom Harper in Magnificent Maps: Power, Propaganda and Art, a BL exhibition and accompanying book—I think that Harley, in his later writings, and his followers overstate the case, particularly with talk of “subliminal” symbolism.

As someone interested in “nuts-and bolts mechanics” of making a living in the map trade, I am un-persuaded.

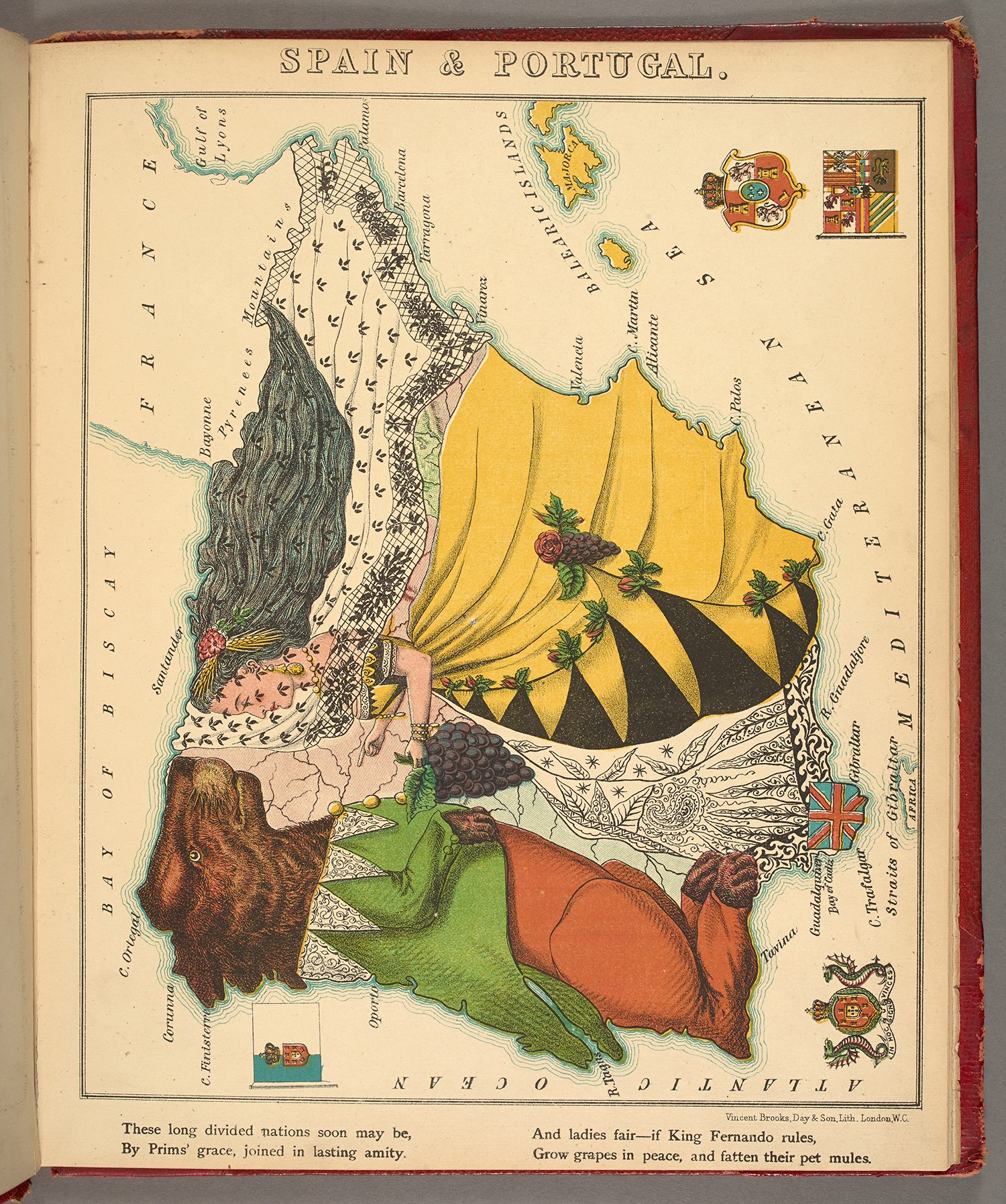

Map of Spain and Portugal, 1868.

What do these curious maps tell us about the people who made them and about the times they were made in?

A difficult question to answer. My view is next to nothing about the makers; as I suggested above, others would disagree (profoundly, perhaps). To use an analogy, if you are a baker and love marzipan but your customers don’t, do you make your next batch of cakes with or without marzipan? I’d suggest that maps by commercial publishers, who are trying to make a living, tell us a lot about the buyer, and the period they live in and the environment they are familiar with, but not the author. The author / mapmaker is trying to produce maps that sell, so targeting (marketing to—which is by no means a twentieth century invention, whatever some of the books say) his audience, the market place, and that marketing is direct and not subliminal—whether the Leo maps celebrating Holland’s successful struggle for independence, the many British game maps of the late eighteenth century, with their imperial view, the jingoistic maps of the first year of the First World War or the Geographia game “Buy British” from the 1930s.

‘United States, a Correct Outline’, 1880, by Eliza Jane [Lilian] Lancaster

The fascinating thing about curious maps is that, unlike geographical maps which have a defined structure and boundaries, they are really about the maker’s imagination—the mapmaker at play, as I like to say—and that’s why they stand apart from other maps.

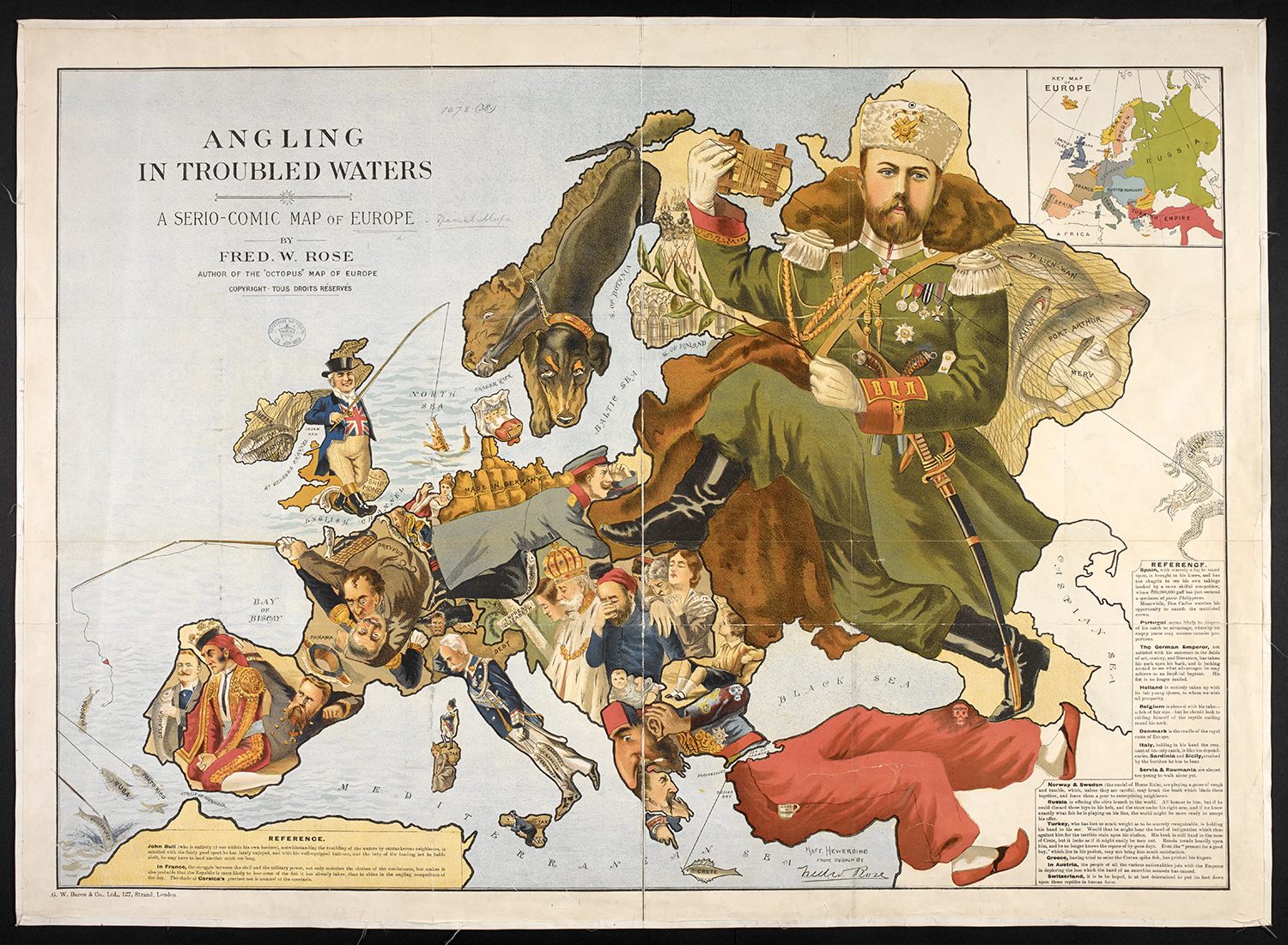

An 1899 map ‘Angling in Troubled Waters. A Serio-Comic Map of Europe’.

But, they exist because the publisher, with his investment in producing the maps, saw a market for it. And, fortunately for us, they appealed sufficiently to a buyer to be acquired and then kept, when so many maps of this ephemeral time simply were not, before finding their way into the BL (as one of any number of treasure houses of such things) to be preserved for previous, current and future generations to admire (and covet).

‘An Ancient Mappe of Fairyland Newly Discovered and Set Forth’, 1918, by Bernard Sleigh

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook