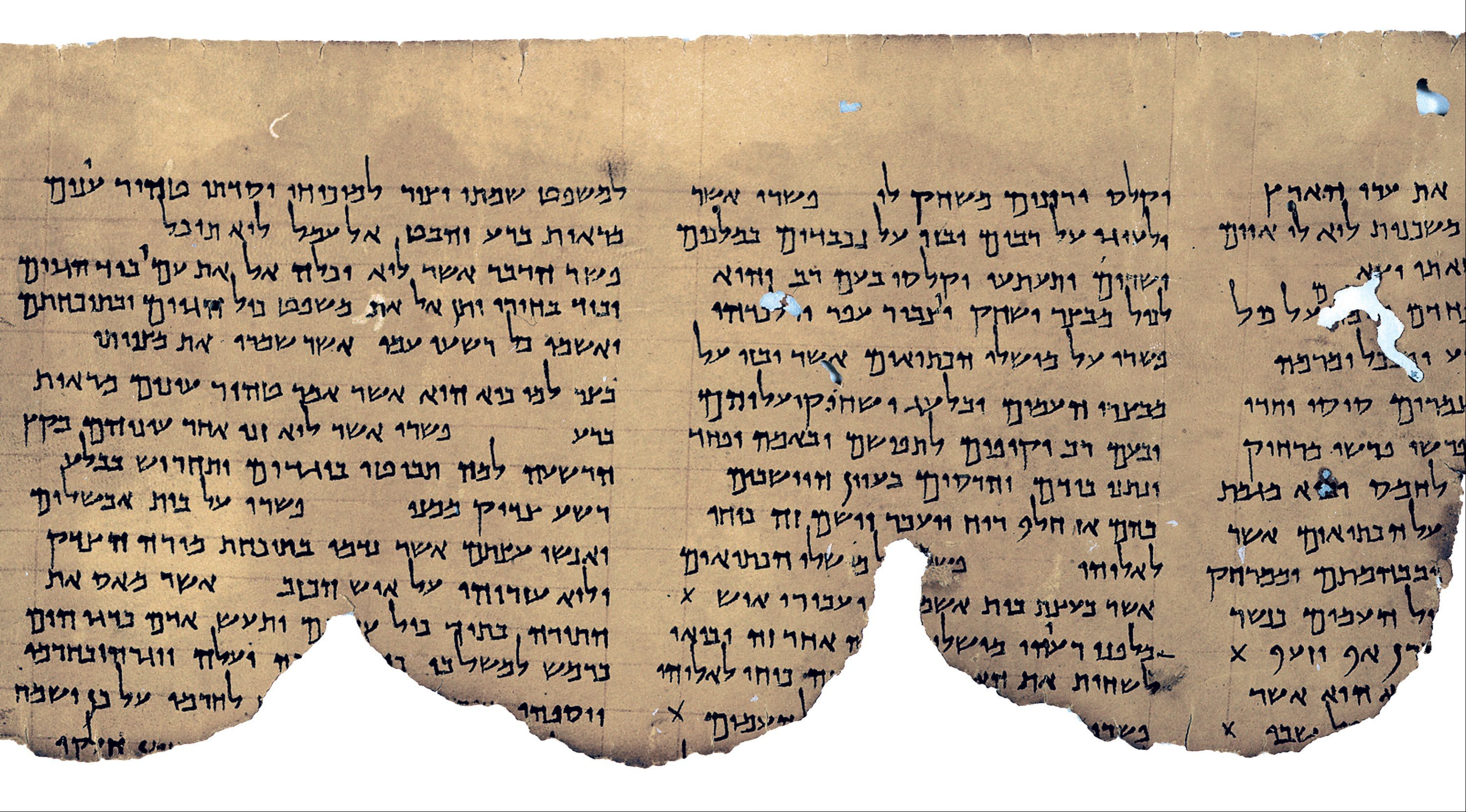

One of the Last Two Dead Sea Scrolls Has Been Decoded

Israeli researchers found an ancient calendar by piecing together fragments of the text.

Sometime around the cusp of 1947, a teenage shepherd in the West Bank threw a rock, possibly to scare an animal out from a cliffside cave, and triggered one of the most incredible archaeological discoveries of the past century. Instead of a thud, a splash, or even a crash, he heard a shattering noise from within the cave, where the rock had hit a cache of large clay jars. In them were leather and papyrus scrolls. Later discoveries in caves in this area would shore up fragments of some 900 manuscripts in Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek.

These texts, known as the Dead Sea Scrolls, have proven a source of fascination to scholars. But their precise origins remain opaque, beyond that they seem to have been written by an ancient Judean sect, the Essenes, and date to at least the 4th century BC. Now, Israeli researchers claim to have “solved” one of the final two scrolls, piecing together 60 of these tiny fragments and, in the process, identifying the name of a festival marking the changes between seasons: tekufah.

Speaking to Haaretz, Dr. Eshbal Ratzon and Professor Jonatan Ben-Dov from the Bible Department at Haifa University explained that by decoding and reconstructing one of the final two scrolls, they were able to uncover a 364-day calendar used by the ascetic sect. Their work was recently published in the Journal of Biblical Literature. This calendar seems to have been a source of struggle between the sect and the Temple, Ratzon said. “But this calendar was disputed, which may be one of the reasons this sect left the Temple and went to the desert. They had many disputes and this was one of them—they couldn’t celebrate holidays together.”

The decoding reveals more about the sect’s calendar, they said—that it begins on a Wednesday, which was when all holidays were celebrated, and that there were additional harvest holidays. It also appears to have been a collaborative effort—the original scribe forgot some words, and a later one fixed their mistakes, filling in omissions and making comments in the margins. “What’s nice is that these comments were hints that helped me figure out the puzzle—they showed me how to assemble the scroll,” Ratzon told the paper.

Lawrence H. Schiffman, Professor of Hebrew and Judaic Studies at New York University, speaks with excitement about the paper, which he describes as “amazing, as a feat of excellent scholarship.” While the source had been readily available for some time, he says, these scholars had managed to painstakingly illuminate a hitherto problematic text. “They’ve basically brought another text to light that we didn’t have,” he says. “This is a really fantastic thing.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook