Deaf-Owned Restaurants Offer Cuisine and Community

Around the world, cafés and eateries are sharing Deaf culture.

Imagine walking into a popular restaurant in a trendy neighborhood. Instead of hearing, “Good evening, how many in your party?” you are greeted by a silent but smiling host, who uses gestures to show you to your table. You’re puzzled, until you read the menu’s explanation that the entire restaurant staff is Deaf, and you will need to order without speaking.

Over the last decade, Deaf-owned restaurants have sprung up around the world, serving everything from pizza and crêpes to vegan fast-food and Moroccan couscous. While most of these restaurants are independent endeavors, all are examples of a growing desire within the community to own and patronize Deaf-owned businesses.

Dr. Thomas K. Holcomb is a professor, author, a member of a multi-generational Deaf family, and an expert on Deaf culture. “There is a Deaf can-do attitude that motivates Deaf people to become whatever they dream of being,” he says. But if a Deaf person aspires to work as a chef, they may struggle to get hired in a restaurant, because of the concern that communication challenges could slow the frenzied pace of a busy kitchen where everyone else can hear.

One solution is a restaurant completely staffed by Deaf workers. Sid Nouar, owner of 1000&1 Signes in Paris, welcomes his guests with a warm smile and an inviting gesture. In 2001, he was the first Deaf person to open a restaurant in France. In the beginning, Deaf Parisians couldn’t believe that his small space housed an actual Deaf-owned restaurant, and a line trailed out the door every day.

Aware that the unemployment rate among Deaf people worldwide is 70 percent, Nouar tried to hire an all-Deaf staff, but couldn’t find any experienced Deaf waiters. So, while his Moroccan mother did most of the cooking, he worked alone serving lunch and dinner six days a week, until he burned out.

After a few years to regroup, in 2018 he opened a bigger location with an all-Deaf staff. The menu includes classic Moroccan couscous bowls with a choice of meat or vegetarian toppings, kémia or cooked vegan salads, and filled pastry bricks, or warqa. For dessert, he serves crescent-shaped almond cookies with strong mint tea. His positive reviews have now attracted a largely hearing clientele. Meanwhile, Deaf Parisians still thrill at being to order in LSF, Langue de Signes Français.

Although every country has its own unique sign language, Deaf people across the globe share many common experiences, especially the frustration of primarily communicating in a language not shared by the majority. Instead of focusing on what they cannot access, however, many Deaf people take pride in their rich sign languages, plus the arts, athletics, folklore, values, and history that make up what is known as Deaf Culture.

That same pride is being channeled into what is called the “Deaf Ecosystem.” Amongst members of the global Deaf community, there is a growing emphasis on supporting Deaf-owned businesses and Deaf professionals whenever possible. “It is a source of pride in collectivist Deaf culture … to travel long distances to support these Deaf entrepreneurs and businesses,” says Holcomb. “Trips may be planned around visiting Deaf-owned restaurants as well as the landmarks in, say, Paris or Tokyo.”

When visiting Austin, Texas, Deaf travelers are sure to visit Crêpe Crazy. The birth of this popular crêpe restaurant evokes the quintessential American fairytale: two Deaf immigrants turn a secret family recipe into a pair of successful central Texas restaurants, serving an American take on a European classic.

Vladimir and Inna Giterman, originally from Russia and Ukraine, met in Belarus. They moved to the US in 1990 to seek opportunities offered to Deaf people. When they were inspired to start a business, they took Vladimir’s mother’s recipe for little blinis and turned it into large, filled crêpes, selling them from a small food truck which they took around to festivals. In 2014, they opened a cafe in Dripping Springs, followed by a restaurant in Austin, two years later. Their two children, Michelle and Sergei, now help run the family business.

Michelle and Sergei, as well as most of the restaurant staff, are Deaf. It is common practice at Crêpe Crazy and other Deaf-owned restaurants to hire Deaf contractors, electricians, woodworkers, painters, and even Deaf artists to decorate the walls. This mutual support keeps the Deaf Ecosystem running. In 2020, the Gitermans franchised a third Crêpe Crazy in Baltimore, to another Deaf couple. To them, keeping business within the Deaf community is important.

An all-Deaf workforce at a restaurant means clear and easy communication between the chefs, wait staff, and dishwashers through sign language. This arrangement is especially appreciated by Deaf diners. Finally, they can ask their server to describe the day’s specials in detail, inquire about a wine recommendation, or make a request regarding a food intolerance. In sign language, everything will be perfectly clear.

Deaf-run restaurants offer a different kind of access for their hearing diners, who usually make up 80 percent of their customers. Many of these restaurants’ menus caution diners that yelling will not attract the attention of their Deaf servers. The menu at L’Oreille Cassée, (which means “broken ear”) a cozy tapas restaurant in Toulouse, France, suggests waving your arms instead. Once you get the waiter’s attention, you can order one of their specialties, like accras de morue (salted cod fritters).

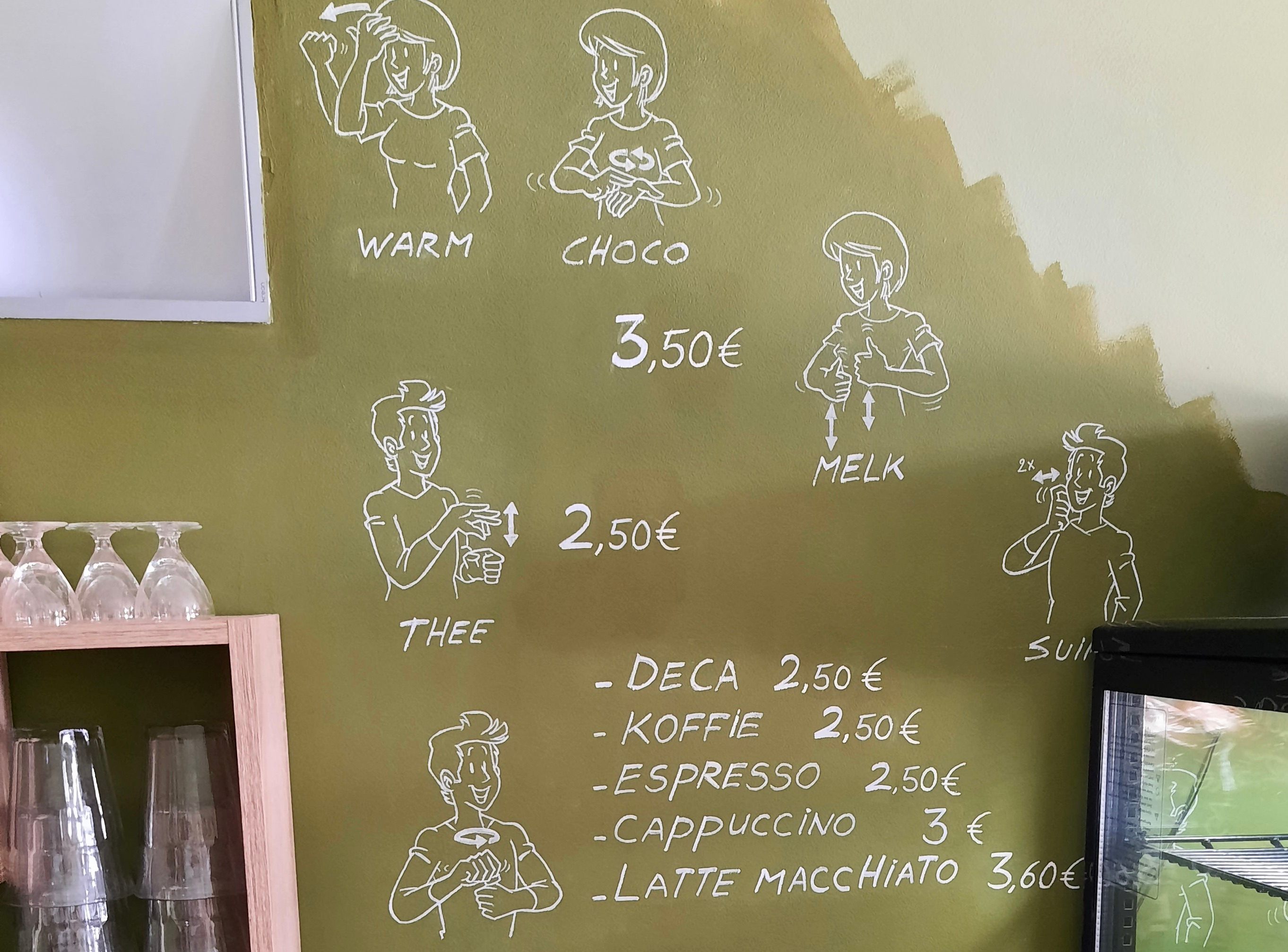

Some restaurants, like 1000&1 Signes, post illustrated pictures on their menu or wall for the signs used to describe their dishes. Other times, orders can be written or texted. At Crêpe Crazy locations, a wooden sign with a large hand says “Point and Ye Shall Receive,” so hearing customers who don’t sign will know the easiest way to order.

The sunshine-yellow walls of Bravo Caffè in Taipei, Taiwan, are decorated with illustrations of essential signs in Taiwanese Sign Language, such as “good morning,” “coffee,” “tea,” “hot”, and “yummy.” But any customer can easily order, thanks to their large point-and-order menu with a selection of lattes, coffee, and teas.

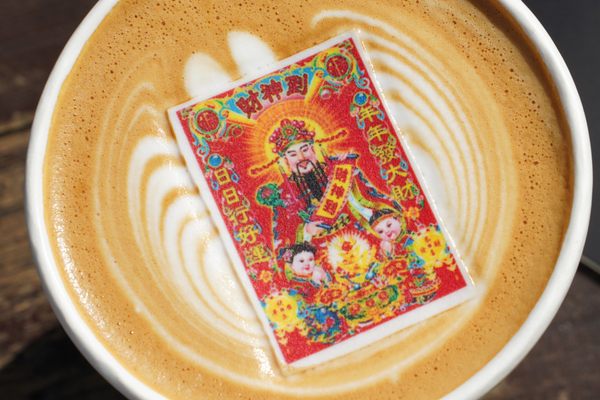

Owner Johnny Lo discovered coffee when he was 15. It tasted so good that he hoped to one day have his own coffee shop. After working as a digital art designer, Lo changed careers to open his dreamed-of café at age 49, with his wife Mandy Chang. Any coffee drink ordered is sure to be a work of art: topped with foamed milk flowers, hearts, and swans. Prior to opening, Lo trained for months with a private teacher to master all the necessary skills. When he retires, he wants to hand the cafe over to a young Deaf entrepreneur.

There are other restaurants around the globe with Deaf workers, but not Deaf owners. Some may have been established by disability support groups, where hearing proprietors hire Deaf workers to provide them with jobs which might otherwise be hard to come by. By contrast, Deaf-owned shops are the result of determined entrepreneurs eager to showcase the fact that they can accomplish great things when given the opportunity.

Beyond offering a good meal, many such restaurants aim to introduce Deaf culture and sign language to their hearing patrons. That’s one of the goals of Christophe Taveirne, the owner of Soepbar Sordo in Ghent, Belgium. “I want hearing people to know Deaf Culture, so the seeming anxiety some have disappears and turns into a respectful curiosity,” he explains. Taveirne’s intimate soup café opened in 2016 and is the first Deaf-owned restaurant in Belgium, to his knowledge. He has one Deaf staff member and says that their interaction “shows hearing clients how sign language communication works, how quick it is.”

Taveirne serves three vegan soups daily, plus sandwiches, homemade apple pie, tiramisu, and Spanish tapas. To help his hearing customers order, the walls sport painted illustrations of the signs for his dishes. Despite the communication challenges, Taveirne volunteered for years in professional kitchens to gain experience before finally opening his own. He borrowed the Spanish word for Deaf, sordo, for his restaurant’s name, because, he says, “I was inspired by the warmth of Spain to bring some of its coziness to Ghent.”

There are not many spots where Deaf and hearing people can interact casually. “For hearing students learning sign language, these restaurants offer the perfect venue to practice their language skills,” says Holcomb. “Some hearing parents will bring their Deaf children to Deaf-owned restaurants to boost their confidence and pride in who they are and to give them hope for a bright future.”

Hearing diners may leave their first meal at a Deaf-owned restaurant not only satisfied by the food they enjoyed, but with a new appreciation of a different culture. Not surprisingly, the sign that most hearing patrons ask to learn before they leave is the one for “thank you.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook