Dorothy Arzner, Hidden Star Maker of Hollywood’s Golden Age

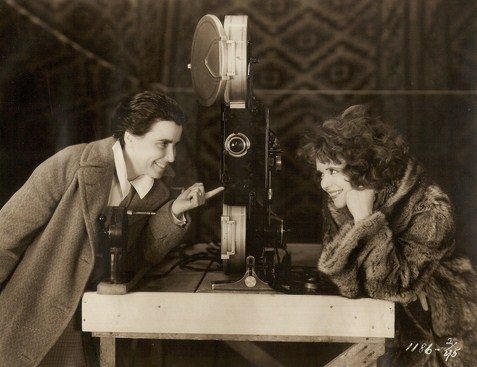

Dorothy Arzner (left) and Clara Bow on the set of The Wild Party (1929). (Photo: Public domain/Wikipedia)

Type the name “Dorothy Arzner” into Netflix’s search bar and you’ll get zero results.

It’s an odd outcome, considering Arzner, a prolific golden age film director, has 16 feature films—among the most of any woman in Hollywood, ever. She gave Katharine Hepburn one of her first starring roles. She navigated the transition from silent films to talkies with panache, inventing the boom microphone in the process. And yet, she is largely unknown today.

Born in San Francisco in 1897, Arzner attended the University of Southern California with the intention of becoming a doctor. World War I interrupted her studies, but when it was over, she decided not to go back to medical school. “I wanted to heal the sick and raise the dead instantly. I didn’t want to go through all the trouble of medicine,” said Arzner, according to the book Directed by Dorothy Arzner. “So that took me into the motion picture industry.”

Arzner’s film career began in 1919 with a trip to the Famous Players-Lasky Corporation—the film studio that would later become Paramount Pictures—at the invitation of director William DeMille. Exploring the various departments, Arzner gauged which aspects of filmmaking held the most appeal for her.

“I remember making the observation, ‘if one was going to be in the movie business, one should be a director because he was the one who told everyone else what to do,’” she said, according to What Women Want: The Complex World of Dorothy Arzner and Her Cinematic Women.

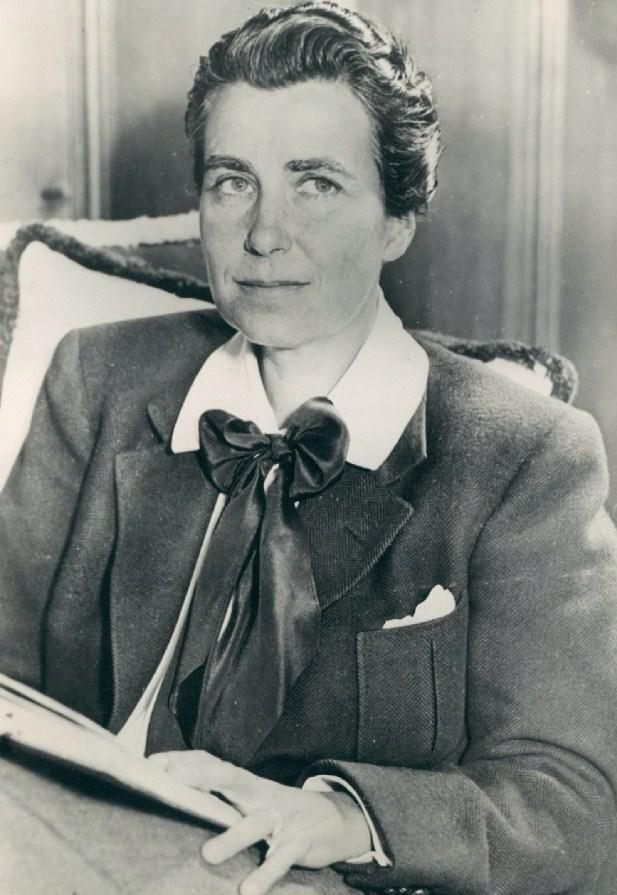

Dorothy Arzner in a publicity still circa 1934. (Photo: Public domain/Wikipedia)

It would take years, however, before Arzner got the chance to prove her directing chops. She began working at the studio as a script typist, tapping at a typewriter all day. Though the work was humdrum, the opportunity to read major Hollywood scripts helped hone her instincts for what made a good film.

The short-lived stint as a script transcriber—she was a less-than-stellar typist, and lasted only three months—was followed by a solid run in the Paramount editing bay. In 1922, while editing the dramatic film Blood and Sand, about a peasant who becomes a champion bullfighter, Arzner saved money by intercutting stock footage of bullfights into the narrative. It was a shrewd move that both endeared her to the purse-string holders and helped establish her as a filmmaker with a keen eye.

By 1927, Paramount was ready for Arzner to take the reins on a studio feature. They assigned her Fashions For Women, a silent film about a cigarette girl named Lulu who impersonates Celeste de Givray, the best-dressed model in Paris. The novelty-ridden hi-jinks—actress Esther Ralston played both roles—didn’t set the world on fire, but the film gave Arzner the opportunity to put what she’d learned into practice. And there was much more to come.

In 1929, Arzner helmed one of Paramount’s first talkies, The Wild Party. It was a star vehicle—and the speaking debut—for silent film it-girl Clara Bow, who, though just 24 at the time, had already appeared in over 50 dialog-free movies.

Clara Bow with Fredric March in The Wild Party. (Image: Public domain/Wikipedia)

Bow had an expressive face that the camera loved, but her Brooklyn accent and lack of experience with sound recording affected her confidence. Nervous among the microphones, the actress would glance at them during takes, ruining shots. It was in these circumstances that, according to When Women Call the Shots: The Developing Power and Influence of Women in Television and Film, Arzner “invented the boom microphone by fastening a microphone to a fishing pole, to give the stars greater flexibility.” (Arzner, however, did not patent her invention—a patent for a very similar sound-recording device was filed one year later by one Edmund H Hansen, a sound engineer at the Fox Film Corporation.)

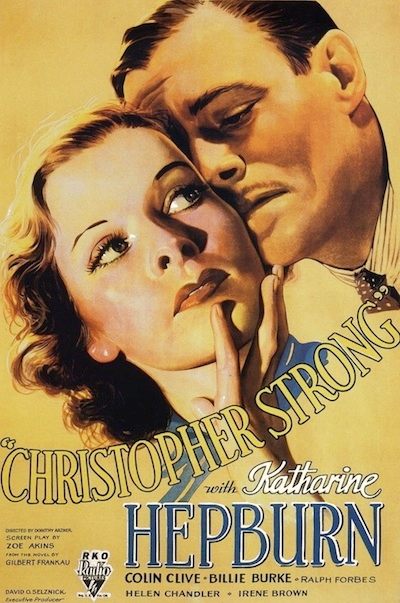

In 1933, Arzner scored big with Christopher Strong, which featured Katharine Hepburn in her second film role ever. Arzner made a point of personally selecting Hepburn for the starring part of the strong-willed yet self-sacrificing aviator Lady Cynthia Darrington.

“I chose to have Katharine Hepburn from seeing her about the studio,” Arzner said in an interview published in Cinema in 1974. “She had given a good performance in Bill of Divorcement (1932), but now she was about to be relegated to a Tarzan-type picture. I walked over to the set. She was up a tree with a leopard skin on! She had a marvelous figure; and talking to her, I felt she was the very modern type I wanted for Christopher Strong.”

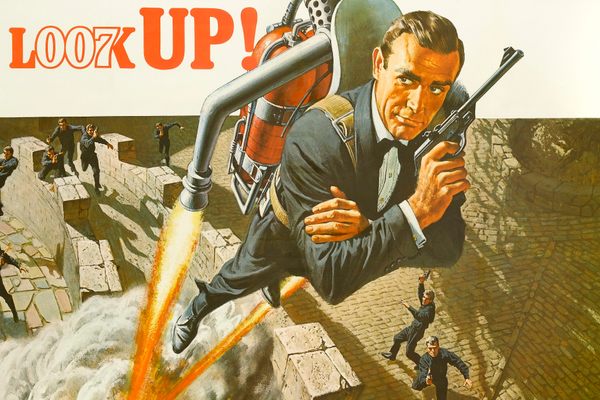

The poster for Christopher Strong. (Photo: Fair use/Wikipedia)

In her autobiography, Me: Stories From My Life, Katharine Hepburn gave a succinct summation of her experience on Arzner’s film:

“She had done many pictures. Was very good. … She wore pants. So did I. We had a great time working together. The script was a bit old-fashioned and it was not a really successful picture. Colin Clive played the man.”

The New York Times review of the film was a bit more forthcoming:

“Intelligence shines throughout this offering, not only in the unusually effective delineation of characters by the players but also in the cinematic angles. Because it is a tragic tale it may not have the strong popular appeal of those offerings which wind up with the pretty girl and the handsome young man in each other’s arms. As a study of worth-while screen work it is, however, far above mediocre shadow adventures. It is a film that can be seen several times without becoming tedious”

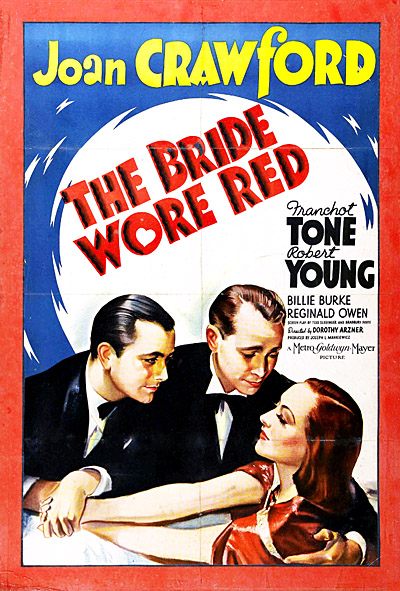

For The Bride Wore Red (1937), Arzner teamed up with star Joan Crawford, who played a cabaret singer who poses as an aristocrat in a fancy resort. She was sent there by a Count to test his theory that “luck of birth is all that separates the rich from the poor,” and once there, she attempts to find a rich husband. The less-than-glowing New York Times review was sprinkled with back-handed compliments: “If it is anything at all, it is a woman’s picture—smoldering with its heroine’s indecision and consumed with talk of love and fashions.”

The poster for The Bride Wore Red, starring Joan Crawford. (Image: Public domain/Wikipedia)

This notion of the “woman’s picture” chock-full of “love and fashions” is patronizing of course, but it was also daring to present a film like this, featuring a Svengali sending a woman into a kind of social experiment. Arzner’s films managed to be edgy while still fulfilling the requirements of the Hollywood studio system.

“The films depict thwarted relationships, missed opportunities, marriage breakups, and even death,” writes Donna R. Casella in What Women Want: The Complex World of Dorothy Arzner and Her Cinematic Women, “In her handling of the women’s picture, then, Arzner managed to play both sides—satisfying her studio bosses with the popular, conventional love and marriage stories that studios and press could easily spin for their own ends, while challenging the thematic center of those narratives: women’s expected social roles.”

Which is not to say that the director’s own sartorial stylings didn’t have an impact. ”Arzner’s image offers many delights—the expensive tailoring details on her suits, her patterned ties, cufflinks, white shirts, and jodhpurs worn with boots, one leg coolly crossed over the other,” writes Jane Gaines in Jump Cut. She and Katharine Hepburn may have both worn pants, but Arzner was more consistently butch.

Though Arzner never made any official statements regarding her sexuality, her forty-year relationship with choreographer Marion Morgan was no secret. Rumors that Arzner was romantically involved with Joan Crawford and Katharine Hepburn—not, to be clear, simultaneously—have never been confirmed.

A shining example of Arzner’s artistry is Dance, Girl, Dance, a 1940 film starring Lucille Ball as a bawdy burlesque dancer named Bubbles who competes for stage time and male attention against Maureen O’Hara, portraying the earnest ballerina Judy. In the words of Sophie Mayer writing for Sight & Sound, the duo spend much of the film “tiffing and dancing like a crypto-lesbian Fred and Ginger.” But amid the screwball capering is a scene in which O’Hara’s character, furious at being disrespected and belittled by the mostly male audience, stops dancing, walks to the front of the stage, and confronts the hecklers:

”We’d laugh right back at the lot of you, only we’re paid to let you sit there and roll your eyes and make your screamingly clever remarks. What’s it for? So you can go home when the show’s over, strut before your wives and sweethearts and play at being the stronger sex for a minute? I’m sure they see through you. I’m sure they see through you just like we do!”

Arzner directed her last film, First Comes Courage, until illness forced her to abandon the project in 1943, when she was in her mid-40s. Though she never returned to the Hollywood studio system, Arzner kept directing, tackling Women’s Army Corps training videos during World War II and a series of Pepsi commercials in the ’50s at the behest of Joan Crawford. In 1959, Arzner took up a teaching position at UCLA’s film school, where her students included Francis Ford Coppola.

Dorothy Arzner died in 1979. With 16 feature directing credits to her name—and several other films for which she went uncredited—she remains the most prolific female director that Hollywood has ever seen.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook