This Arctic Ichthyosaur Should Not Exist

A marine reptile fossil from Svalbard challenges ideas about evolution and Earth’s greatest mass extinction.

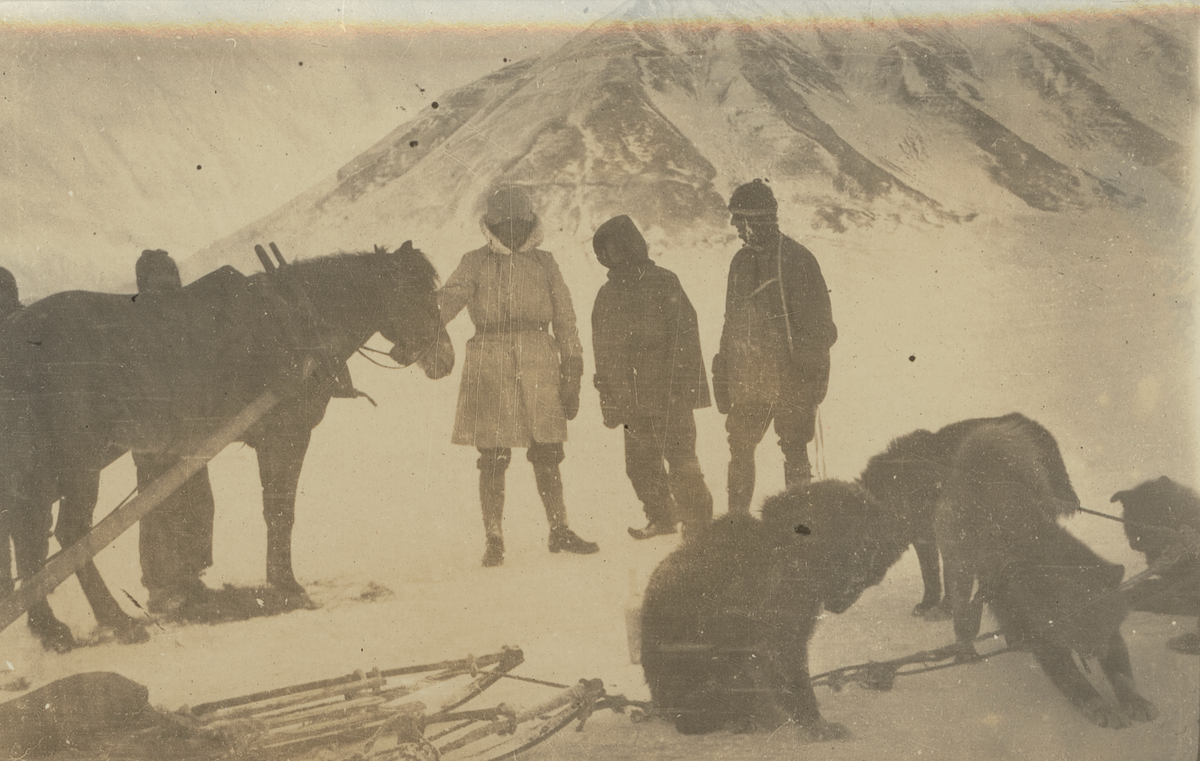

Australian-born Benjamin Kear is a hunter of the High Arctic. With colleague and friend Jørn Hurum, he chose a quarry, and set off across the treeless expanse of Norway’s Spitsbergen, part of the Svalbard archipelago, where wind and snow roar across the landscape, even at the height of summer. There, the steep sides of barren mountains crumble and slump from erosion, exacerbated by the freeze-thaw cycles of melting permafrost. Soft, almost mud-like pieces of shale slide down their flanks, revealing hints of the creature they pursued.

“It’s the hardest field work I’ve ever done,” Kear says, safely back in his Uppsala University office. “You’ve got your rifle on your shoulder and there’s polar bears running around. On our last trip we were stuck in the tents for 36 hours in a blizzard.”

Team members carried the rifles because the archipelago’s polar bears outnumber humans—but they relied on other tools for their hunt. “This is what we’re using,” Kear says, holding up a worn, faded green notebook about the size of a smartphone. “It’s actually the 1929 diary, and I’m hunting through the field notes. The idea is to go back and trace what they were doing when they were finding bits.”

The bits in question are fossils and, for more than a century, other hunters have come to what’s known as the Vikinghøgda Formation in search of bones. The earlier expeditions had mapped their discoveries, and the kinds of rock they were found in, creating a record that Kear and his fellow paleontologists have relied on in their search for the first member of one of Earth’s most successful animal groups. And they found it. Sort of.

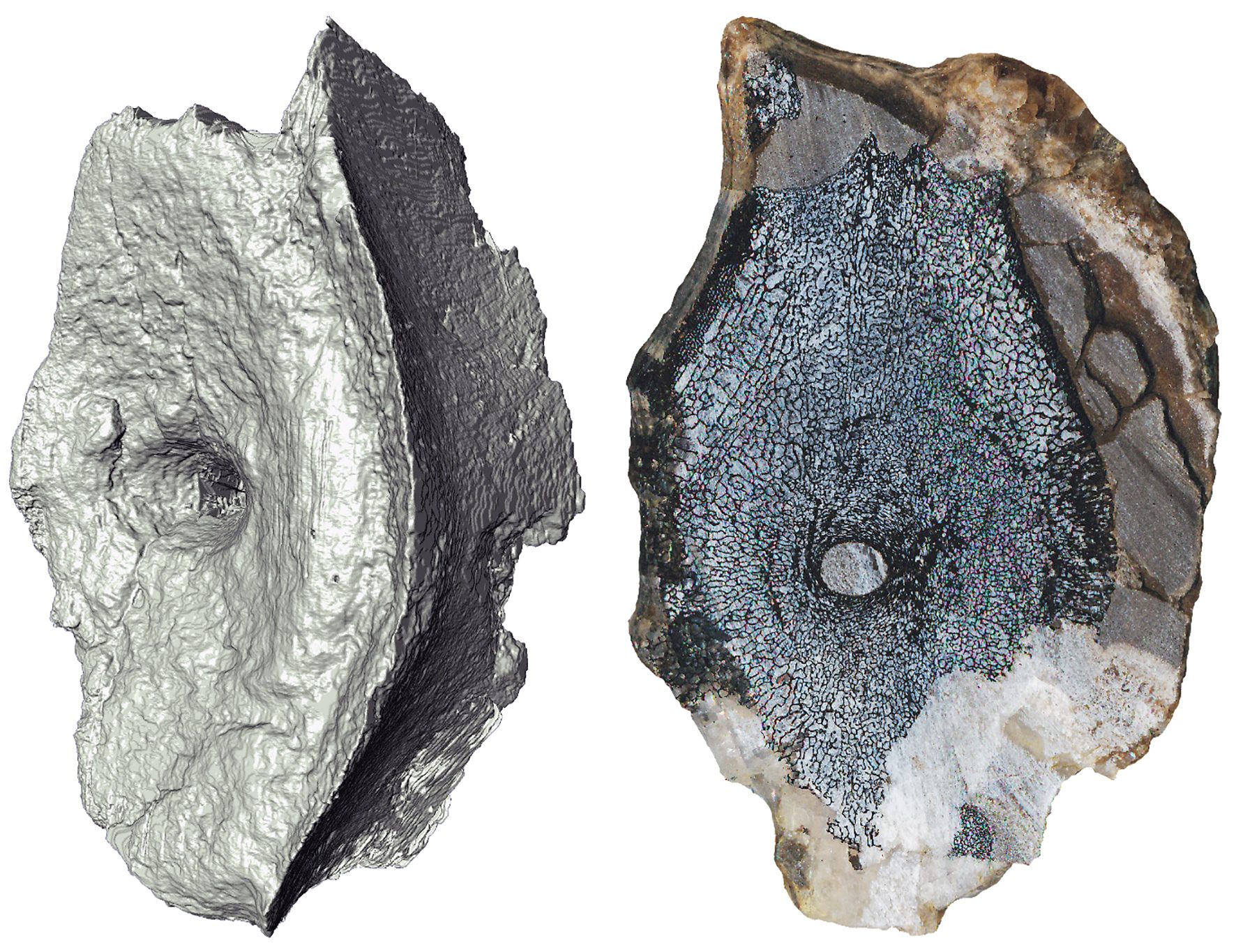

In a recent letter published in Current Biology, the team detailed fossil vertebrae from Spitsbergen that belong to the earliest known ichthyosaur, a kind of marine reptile found the world over during the Mesozoic (sometimes called the Age of Dinosaurs). But there was a problem. The 250-million-year-old fossil vertebrae, collected from Spitsbergen in 2014 but studied only recently, don’t fit Earth’s timeline as we know it—or, at least, as we thought we knew it.

Kear recalls examining the fossils for the first time. “It’s an ichthyosaur, pretty obviously, but the rock is wrong,” he remembers thinking. “This is older than it should be. The first step is, of course, you doubt yourself. You go, ‘No no, this can’t be right.’”

The team conducted an array of tests, including X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy—“basically firing radioactivity at the rock,” says Kear—which provides the material’s unique geochemical signature. The tests confirmed the fossils’ age, putting the Arctic ichthyosaur at the very dawn of the Mesozoic—a place it should not be.

The Mesozoic Era began 251.9 million years ago in the wake of the greatest mass extinction the world has ever experienced: the end-Permian, which wiped out between 90 and 96 percent of all species known from the fossil record. While the cause of such destruction remains uncertain, most scientists believe it was connected to massive volcanic activity in what’s now Siberia, which released an enormous amount of gas into the atmosphere that, says Kear, “drives a mega-greenhouse effect. The world gets really, really warm.

“Yes, this drives extinctions,” he adds, “but it also drives evolution.”

In fact, while dinosaurs arose during, and eventually came to dominate, the Mesozoic, this time is perhaps more accurately known as the Age of Reptiles. After the end-Permian mass extinction wiped out entire ecosystems, it was reptiles that quickly diversified and dispersed to fill the voids. That included land-dwelling reptiles that moved into the water, eventually adapting to life in the open ocean: the ichthyosaurs.

“One of these little creatures trotting around on land made the transition to living in the sea. And it’s the first time that it ever happened,” says Kear. While many terrestrial animal lineages eventually evolved to be aquatic, from whales and seals to turtles and penguins, the ichthyosaurs were pioneers in what he calls an “epic transition.”

“You’re modifying your body from laying eggs, walking on limbs, breathing air, everything you need to do on land, to living in water… It’s one of the biggest landmarks in vertebrate evolution and this is why we’re looking for it,” Kear says of his multiyear collaboration with University of Oslo paleontologist Hurum to find the transitional ichthyosaur: the first land reptile to dip its toe, figuratively and literally, into an aquatic lifestyle.

Before the Spitsbergen discovery, the oldest ichthyosaurs in the fossil record were from China, dated to about 248 million years ago. “The problem is, [they] already look like fish: long bodies, flippers, modified tail [with] a fin,” says Kear. “They’re living in water and they don’t come out of it.”

That meant the transitional ichthyosaur, at least by conventional timelines, had to have lived between the end-Permian and the time of the fully aquatic animals found in China—and that’s what sent Kear and colleagues north. “The Scandinavian Arctic preserves rocks of exactly the right age,” Kear says. “You have hundreds and hundreds of meters of continuous sedimentation of ancient seafloor just piled up.”

After fieldwork in Greenland, Kear joined Hurum in Spitsbergen in 2019, turning up several promising finds that season. The pandemic put the team’s expeditions on hold, so the paleontologists ventured into the archives of their institutions to examine material collected from the Vikinghøgda Formation in years past. It was there that they found multiple vertebrae and some fragmentary bones from an ichthyosaur that would have been about 10 feet long, larger than most other animals at the time. When it lived, what’s now Svalbard would have been open ocean, far from land, and it was fully adapted to that environment, with vertebrae very similar to those of modern whales, which likely took about 10 million years to transition from land to sea.

“Ichthyosaurs, like whales today, reduced the amount of bone in their skeleton for buoyancy,” says Kear. “When you look at whale bone, it’s like sponge, because they [also] deposit oil in their bones. Their skeletons float. Ichthyosaurs did the same thing.”

Later ichthyosaurs, such as a 180-million-year-old Jurassic specimen described in Nature in 2018, even had blubber, another adaptation they share with whales and other modern marine mammals that are pelagic, or oceanic. While it’s not possible to say whether the Spitsbergen animal had blubber, Kear says, “You can look at bone microstructure to get an idea of just how pelagic the animal was. [The Spitsbergen ichthyosaur] is not an early transitional form. It’s identical to an advanced ichthyosaur from the Jurassic.”

Kear and colleagues had found the oldest known ichthyosaur—but it was not a land animal, or in the process of transitioning to the sea. It was already highly adapted to life in open water, which presented a new problem. Paleontologists have long believed that ichthyosaurs evolved after the end-Permian. How could a terrestrial animal transition from land, to a coastal area, to the deep ocean in the eye-blink, geologically speaking, between a mass extinction and the Spitsbergen find?

“To squeeze evolution that dramatic into that amount of time, it’s unprecedented,” says Kear. “Take our own evolution. To create the hominin, the walking, big-brained thing building space shuttles and gin and tonics, it took over four or five million years, and that’s already from an upright ape, for want of a better word. You’re talking about something scuttling around on legs transforming into something that looks like a fish in under two million years.”

There is only one logical explanation, as the team sees it: The ichthyosaur lineage did not evolve in the wake of the end-Permian cataclysm—the animals survived it.

“Whichever way you cook it, they were there,” Kear says. “They were there before the extinction.” And if ichthyosaurs predated the end-Permian and hung on to thrive in the Mesozoic, what other animals might also have endured, challenging our ideas of the biggest extinction event in the history of life on Earth?

Vanderbilt University paleontologist Neil Kelley, who studies ichthyosaurs and the evolution of marine ecosystems and was not involved in the research, calls the findings “welcome and intriguing” but also “inconclusive”—the fossils are, after all, only partial remains. He thinks the find could be “a spark to continue pursuing the evolutionary history deeper into the rock record.”

Other paleontologists share Kelley’s enthusiastic but measured reaction to the Spitsbergen fossil: “The vertebrae are absolute giveaways, and this is a proper ichthyosaur vertebra!” says University of Bristol paleontologist Michael Benton, who was not involved in the research. But Benton also remains unconvinced that it’s time to overhaul our understanding of the end-Permian, including which animals may have unexpectedly survived into the Triassic, the first period of the Mesozoic.

“Don’t rewrite the textbooks, but change ‘Ichthyosaurs evolved fast after the mass extinction’ to ‘Ichthyosaurs evolved very fast,’” says Benton, who coauthored a 2022 Frontiers in Earth Science paper about the massive and rapid diversification of marine life during a “Triassic Revolution.”

And whether ichthyosaurs evolved before or after the end-Permian, their ability to hang on during this period is itself notable, Benton adds. “The post-extinction world of the Early Triassic was not benign; things had not simply returned to normal. The Early Triassic was punctuated by global warming crises and further extinctions, at least three times. In these challenging conditions, it was difficult for anything to make a reasonable recovery, and especially a top predator, such as an ichthyosaur.”

Hefei University of Technology paleontologist Jun Liu, who has also studied the rapid evolution of marine ecosystems during this period, is confident—and excited—that the Spitsbergen fossil material belongs to a fully oceanic ichthyosaur. But he’d like to see additional fossils found from new excavations at the site to confirm its age. “The authors did excellent geochemical analysis,” says Liu, but, due to the eroding, shifting landscape of slumping shale, the material was not found in its original location.

Vanderbilt’s Kelley, while agreeing that the Spitsbergen fossil seems to be from an ichthyosaur or close relative, also believes finding more bones from this earliest slice of the Triassic is important: “There’s a chance it could be something else, particularly because we don’t have other fossils of this age to compare with.”

Liu and Kelley may get their wish: Kear and Hurum plan to return to the site this July. “The most exciting part is that the walking ichthyosaur is still out there, waiting to be found,” Kear says. “I fully expect it to pop up. We’re going back to Svalbard and we’re going to hunt like hell to find it.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook