Empanadas With a Taste of Venezuelan History

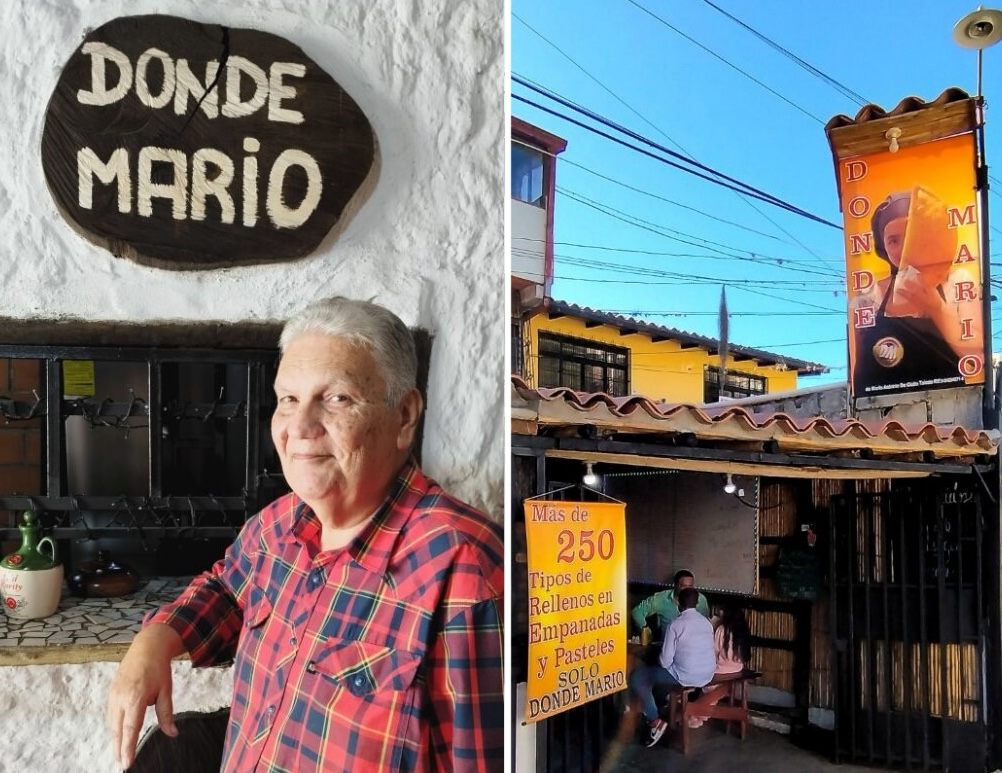

At Donde Mario, empanadas often come with a lesson about the past.

Empanada stands in Venezuela tend to draw customers looking for a quick and easy breakfast. But at Donde Mario, located in one of the poorer shantytowns of Mérida, the pastry packages come with historical pedigree.

“You can fantasize about dishes by traveling through different time periods at Donde Mario,” animated customer Paúl Rodríguez tells me after guzzling down his Mantuano chicken empanada while sitting at a wooden table.

With his eyes twinkling, he explains that his breakfast was “packed full of history, of tradition.” The cause of his excitement? The fact that his empanada had a connection to Simón Bolívar. “El Libertador” is almost a demigod in his homeland of Venezuela, after having cast out the colonial Spanish with his army of slaves, peasants, and indigenous warriors between 1810 and 1830.

The Mantuano empanada is based on polvorosa de pollo—sweet cakes stuffed with a mix of chicken, raisins, capers and olives, all with a generous dash of red wine. The cakes were extremely popular with the white landowning pre-Bolívar colonial elite in Caracas, who were known as Mantuanos. But little did Rodríguez realize that he and Bolívar shared the same vivid gusto for this 1750s dish until he got an impromptu history lesson from Mario de Giulio, the owner of Donde Mario. Today, this mixture is stuffed into what de Giulio calls his Mantuano empanada, and he’s happy to tell any customer about the filling’s history.

It is just one of the impressive 251 empanadas de Giulio offers in La Milagrosa barrio, where he combines popular breakfast pastries with his vivid passion for the past.

De Giulio never studied cooking. His first culinary project was sweet-and-sour goat while on the road as a traveling shoe salesman, a profession that took him to Italy and Germany, among other places.

His natural creativity and drive led him to open his empanada bar in 2016. He notes that it was “possibly one of the harshest years in Venezuela’s history,” due to a devastating economic crisis. He rapidly learned that food was more than fine ingredients and culinary technique. “Good conversation is an integral part of a good meal,” he explains. “Many people come just to chat with me. They often eat later.”

But the 65-year-old cares about more than conversation. Instead, he sees his cooking’s historical roots as a way to illuminate the past. “Today, the educational system is totally deficient compared to the education we had 40 years ago,” he says. “Venezuelans had much more interest in history before. I come from a generation in which personal growth and study were constant.”As the rich aromas start to swirl out of the kitchen, the larger-than-life chef strides over to a family ordering an empanada straight out of Caracas’ annals of exploitation and power.

“Asado negro, like many marvelous dishes, was invented by accident,” he tells the astonished customers. “A slave cook burnt a steak in Simón Bolívar’s family home. The desperate woman didn’t know what to do with it and ended up cooking it in molasses.”

The cook was more than successful in hiding her mistake. “When the owner of the house, who was almost certainly Simón Bolívar’s father, came home, he loved the meal and ordered her to continue to make it,” de Giulio says. Interestingly, it was Bolívar (who grew up reportedly adoring asado negro) that kick-started Venezuela’s abolition of slavery in the early 19th century.

A quick coffee later and it is teaching time again when a customer orders a Burnt Village empanada, much to de Giulio’s delight, as this tale conjures up scenes of bloody battles against foreign invaders.

Chiguará is a small village close to Mérida that is now famous for producing the soft cheese de Giulio uses in this empanada. In 1657, during the Spanish conquest, well-equipped soldiers failed twice in their efforts to defeat the settlement’s indigenous warriors at great embarrassment to the invaders.

“Out of a sense of impotence, the Spanish commander ordered the village to be scorched to the ground. One week later, his army took it. The residents who survived started to be known as the people of the burnt village, and that’s why I called this the Burnt Village empanada,” he recounts, noting that many Venezuelans, including even some residents of Chiguará, don’t know the story.

But de Giulio’s clientele are a rapt audience. “It’s marvelous that [de Giulio] revives our history,” customer Elkis Vangor tells me. Another, Gilmer Ardila, agrees. “Here you can try flavors from the past,” he says, after devouring an asado negro empanada. “It was great to find out a bit about the gastronomy of that period and especially because Mario took the time to come and explain a bit to us,” Gilmer’s wife Grecia adds.

De Giulio’s exhaustive effort to investigate and cross-reference the often disjointed tales behind his empanadas is not always easy. “I try to find the origin of some dishes,” de Giulio says, explaining that apart from the internet, he uses age-old books from aristocrats and food writers in local libraries, as well as recipes passed down via word of mouth.

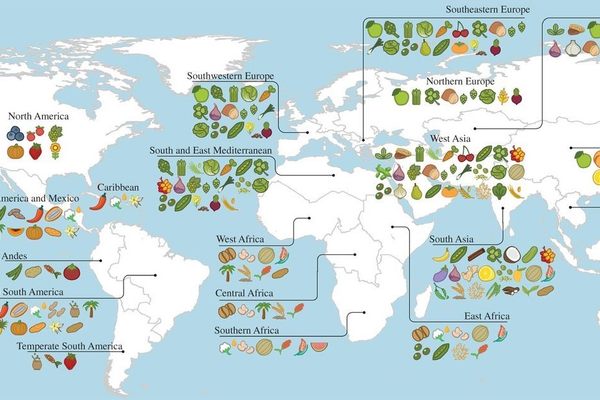

He also has to update some of the recipes to suit modern-day palates, while being careful not to compromise their essence. “Gastronomy has changed a lot in 200 years. If I cooked exactly the same as 200 years ago, no one would like it. Tastes change,” he explains. “Venezuelan dishes are fusions and this allows us greater flexibility.” But his efforts appear to be bearing fruit. Not only is Donde Mario a relaxed, homely venue where he can share knowledge, but his audacious cooking can summon liberating lessons from Venezuela’s turbulent past. “Most people are surprised that I approach them to explain history,” he says. “But it is necessary to look back in order to transform today’s precarious reality.”

According to him, Venezuelan society has made many “political errors” in recent years, starting with the 1998 election of Hugo Chávez and his “Bolivarian Revolution”: a populist project that redistributed the country’s vast oil income. More recently, multi-million dollar corruption and gross public mismanagement, aggravated by a fierce economic blockade from the US and EU, have destroyed Chávez’s reforms and paved the way for a sweeping electrical crisis, hyperinflation, and the steep decline of purchasing power, and a migratory exodus that has broken up families, all with a knock-on effect on Venezuela’s educational institutions.

However, de Giulio still believes in the transformative power of knowledge. “People live in the day-to-day now. But when people study, they start to understand the cage they have been put in,” he says. “I believe in this country, and I try to show people that we can do things differently, we can be creative. Ignorance can be cured by reading, but also through other methods.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook