Europe’s Oldest Map Shows Tiny Bronze Age Kingdom

Discovered in 1900, the Saint-Bélec slab languished unrecognized in a castle basement for over a century.

It’s about 4,000 years ago, and you are the ruler of a prosperous little Bronze Age kingdom at the end of the world. To celebrate your success, you commission a map of your bountiful domain: a stone slab 2.2 by 1.53 meters (6.5 by 5 feet), representing an area of 30 by 21 kilometers (19 by 13 miles). But all good things come to an end. You, or one of your successors, is buried with the slab—broken to indicate the overthrow of your dynasty.

You have the last laugh, though. Your name and that of your little empire have been forgotten, but that slab is now recognized as Europe’s oldest map that can be matched to a territory—even if it took the supposedly clever scientists of the distant future more than a century to figure that out.

In a nutshell, that is the story of the Saint-Bélec slab. In 1900, local archaeologist Paul du Châtellier retrieved it from a prehistoric burial mound in Finistère, the French department on the western edge of Brittany. (Its name means “end of the world.”)

After unceremoniously gluing the pieces of the broken stone back together with concrete, Du Châtellier faithfully reproduced the markings on its surface for a report, in which he noted: “Some see a human form, others an animal one. Let’s not let our imagination get the better of us and let us wait for a Champollion [the Egyptologist who in 1822 deciphered the hieroglyphics, Ed.] to tell us what it says.”

Du Châtellier had the stone, weighing more than a ton, moved to his ancestral home, Château de Kernuz, where he maintained a private museum. The slab was placed in a niche near the moat of the castle. After the amateur prehistorian’s death in 1911, his artifacts were acquired by France’s National Archeological Museum at Saint-Germain-en-Laye but remained on site.

The stone languished in obscurity for decades. In 1994, researchers revisiting Du Châtellier’s original drawing found that the intricate markings on the stone looked a lot like a map. The stone itself, however, had gone missing. It was “rediscovered” in the castle cellar only in 2014.

From 2017 to earlier this year, researchers from INRAP (France’s National Institute for Preventive Archaeological Research) and other institutions carried out extensive research on the slab. Their conclusion was published in March 2021 in the Bulletin de la Société préhistorique française.

And it is spectacular: This is the earliest known example in Europe of a map for which we can identify the territory it depicts. The slab was engraved in the early Bronze Age (2150–1600 B.C.), which makes it contemporaneous with the Nebra Sky Disk, a map of the cosmos discovered in Germany (but not conclusively identified with any particular constellations).

Another famous prehistoric map, from Bedolina in Valcamonica (northern Italy), is dated later, to the Iron Age. The landscape it depicts has not been identified; possibly it is a purely imagined one.

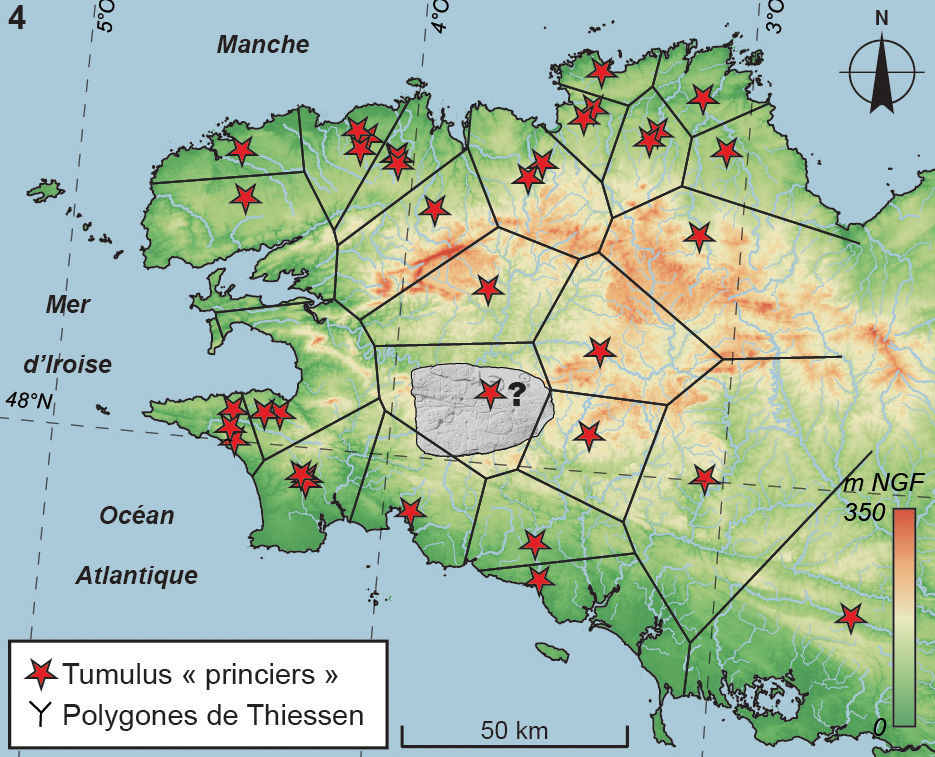

The Saint-Bélec slab is the first map of its kind and age that has been identified with a particular territory. The researchers found that the markings on the slab corresponded to the landscape of the Odet Valley, oriented east-north-east to west-south-west. Using geolocation technology, the researchers established that the territory represented on the slab bears an 80 percent accurate resemblance to an area around a 29-kilometer (18-mile) stretch of the Odet River.

The map is centered on the present-day municipality of Roudouallec, in the neighboring department of Morbihan, but also includes the location of the burial mound in which it was found, more to the west in Leuhan, as well as the foothills of the Montagnes noires (“Black Mountains”).

The surface of the slab had been worked to represent the terrain’s undulations—also making it Europe’s oldest 3D map. Lines correspond to river tributaries. Various other markings (circles, squares) are thought to represent parcelled fields, settlements, and/or burial mounds and perhaps the ancient road from Tronoën to Trégueux. A circular symbol near the source of the Odet (and those of two other rivers, the Isole and the Stêr Laër) may represent the local ruler’s residence.

The early Bronze Age was the time when the first primitive states emerged in western Europe and along with them a network of commercial, cultural, and diplomatic exchanges. This was an interconnected world, and the sea that surrounds Brittany on three sides was a passageway, not a border. In local Breton graves of that time, objects have been found that originated in southern England and northern Spain.

The study speculates that the map might have been made as an expression of political power. But prestige need not have been the only reason. The map may also have served as a land register, to keep track of who did what where—and how much they owed in tax as a consequence.

Whichever purpose it served, the slab may have been in use for centuries, before it was placed in a grave and broken in situ—perhaps a deliberate act of iconoclasm, to indicate the end of the unnamed Bronze Age kingdom. Perhaps the broken map is even an echo of a wider societal change: the end of the Bronze Age kings altogether. After all, it would not be France without the occasional revolution.

The original article, La carte et le territoire : la dalle gravée du Bronze ancien de Saint-Bélec (Leuhan, Finistère), can be previewed and purchased from the Société Préhistorique Française. For more background, see this interview with researchers Yvan Pailler and Clément Nicolas at INRAP (in French).

This article originally appeared on Big Think, home of the brightest minds and biggest ideas of all time. Sign up for Big Think’s newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook