How One Tiny Bead Can Reveal A Global History

Hint: There is a laser involved.

Jessica Thompson was looking for bones, not beads. But as the Yale archeologist sifted through the fertile soil of Kasitu Valley in northern Malawi in the mid 2010s, she kept finding small glass orbs, many about the size of grain of rice. Some were white, others were dotted with red, and a few were either dark blue, blue-green, or turquoise. “I had not expected to really see that,” she says.

These beads were part of the monetary system in northern Malawi in the 18th and 19th centuries. Then, they were used to buy goods and food, pay taxes imposed by local chiefs, and even purchase enslaved people. Today, the 29 beads Thompson discovered are part of a history that is still being written for the under-studied region. According to a paper co-authored by Thompson, the miniature spheres are evidence of direct and indirect trading that was occurring between Europeans and Africans along indigenous trade routes created at least 1,000 years before Europeans began widespread exploration in that region.

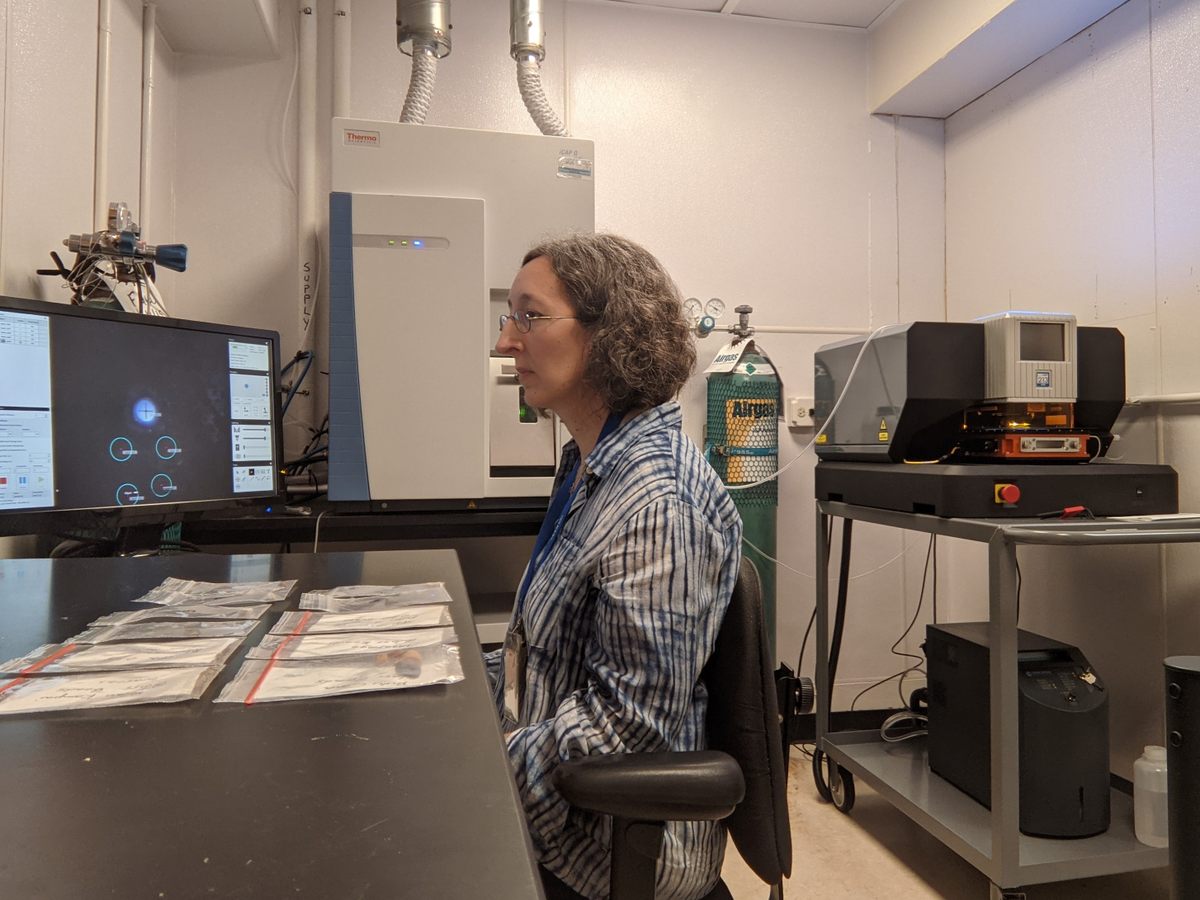

To understand the story of the beads, Thompson worked with Laure Dussubieux at the Field Museum of Chicago, who used a technique called laser ablation inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry to analyze the find. The minimally invasive process involved removing microscopic amounts of material from the beads; the material was then analyzed to determine its chemical components. The results revealed the proportion of each element found in the artifacts, allowing researchers to determine where they came from and the technology used to make them

Some of the beads found in Malawi were so tiny—as little as one millimeter in diameter—that Thompson and her team couldn’t quite figure out what they were. When it came to analyzing them in Chicago, Dussubieux says that having agile fingers was the key. “You had to be very careful when placing the beads on the chamber because the problem with beads is that they roll,” she says.

The study concluded that all but one of the 29 beads were manufactured in Europe between the 17th and 19th centuries. The one non-European bead had a chemical composition of mineral soda-high alumina typical of beads manufactured in South Asia, specifically in Chaul on the Maharashtra coast, India. The beads’ origins suggest that they found their way to Malawi via Indian Ocean trade routes but further research is needed to understand those trading patterns.

This is the first time this technique has been used on glass beads excavated in Malawi but it has previously been used to analyze other archeological artifacts, says Paul Sylvester, a professor of geoscience at Texas Tech University For this study, with which he is not affiliated, Sylvester says the fact that chemical elements like arsenic and lead showed up in the analysis of the beads made it easy to trace them back to Europe because such elements were commonly used in glass-making around the mid-19th century.

The presence of these European beads in Malawi is an indication of the increased interest that Europe had in that region during the 18th and 19th centuries but, as Thompson says, “the trade goods were things that people in the interior wanted and had their own purposes for.” (The only non-European bead is believed to have been brought into the interior in the 16th century by the Portuguese, who knew that African consumers, at the time, preferred Indian beads over European ones.)

Malawi is a landlocked, southeastern African country bordered by Zambia, Mozambique, and Tanzania. According to Thompson, it is a place rich in history and research material but because of a lack of resources, it doesn’t even have a national museum to display any significant findings. For the excavation of the beads, Thompson and her team worked with students from the University of Malawi to encourage them to use archeology as an access point to understand their own stories. “Because historical documents provide so much detail, they tend to be the things you gravitate towards,” she says. “But I think it makes it a little harder to see what the story would have looked like from the perspective of people who were not necessarily writing down what was going on at the time.”

This past summer, Thompson and her colleagues went back to northern Malawi to do more excavation work. They have already uncovered more beads. Now that she knows what she’s looking for, Thompson says, “they’re just kind of sitting here, potentially ready to be analyzed.” They could reveal a history not documented by Europeans exploring the African interior.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook