Every Spring, Montana’s Abandoned Mine Shafts Open Giant Holes in the Ground

A depression in the backyard could be an abandoned mine shaft hundreds of feet deep.

The head frame of an old Butte mine. (Photo: Robert Renouard/CC BY-SA 2.0)

Every spring, Butte, Montana experiences a special rite. The city once called the “Richest Hill on Earth” for its excess gold, silver and copper deposits is now home to hundreds of vertical mining shafts and thousands of miles of tunnels on which the city is built. They’re supposed to be safely filled in. But when the snow turns to rain as temperatures rise, during what Tom Malloy calls “shaft season,” a half dozen or more decide to make a reappearance.

“I’ve opened some of them that are easily hundreds of feet deep,” says Malloy, the reclamation manager of Butte-Silver Bow County and the person who receives the call when a mine shaft opens back up.

Like manmade sinkholes, the earth can open almost anywhere in Butte. Malloy has found tunnels underneath a girl’s swing set, in the middle of a school playground and underneath the back porch of people’s houses. Sometimes people have erected entire buildings over mine shafts: there’s one in the basement of the Acoma, a former hotel, and one in the basement of a bar of Uptown Butte.

Butte in the 1940s. (Photo: Public domain;LOC 1a35027)

Only a few places on the planet have been as heavily mined as this one. Mining here began in 1864, with prospectors looking for gold in the area’s creeks. Soon, though, it became clear that the real wealth was underground. By 1884, there were 300 operating mines in the area and thousands of claims. When the country started being wired from electricity, all of a sudden copper became an incredibly valuable commodity, and Butte was rich in copper, too. By the turn of the century, about a fifth of all copper in the country was coming out of Butte.

With those giant tunnels, sometimes, the earth beneath the town shifts—not dramatically, but enough that sidewalks crack, buildings tilt and windows don’t quite shut properly. But the most immediate problem, each spring, is the unregulated vertical shafts dug in the early days of exploring the area’s mineral resources.

“The ones that turn up were the ones that were dug in the 1880s, 1870s, back before they were well regulated,” says Malloy. “They’re not marked on a map, which would be really nice. But they weren’t required to do that. Those end up being a surprise when they open up. You don’t know if they go down 10 feet and stop, or 1,000 feet down.”

A mine shaft that reappeared. (Photo: Tom Malloy)

Every spring, Malloy ends up investigating 50 to 100 reports of possible shafts, called in by city residents worried about a bit of sinking earth on their backyard or street. First, he and his colleagues will check old maps to see if there’s any indication that a shaft was once dug in that spot. They’ll check whether the alleged shaft is in the historic mining district, and if there have been any other mine shafts found in the vicinity. If they think it’s possible they might be looking at mine shaft, they’ll get the backhoe and do a little test digging to open it up and see what it is. Mine shafts aren’t the only things hiding in Butte’s ground: outhouses sometimes begin to sink into the earth when the ground thaws in the spring.

“There’s no way of knowing until you dig a hole,” says Malloy. “The most recent one, I would have bet $50 that it was an outhouse, but I was proved wrong. I don’t guess anymore, because I’ve been wrong so many times.”

If the backhoe starts bringing up residential knickknacks and materials, that’s an outhouse. If it starts hitting big, structural timbers, Malloy says, that’s a mine shaft.

Timber re-emerging from the ground. (Photo: Tom Malloy)

Often, when miners closed up these shafts, they would cover them with a series of foot-thick wooden timbers, crisscrossed over the mouth of the hole, and pile dirt on top of them. One hundred years later, though, that wood rots out and all the dirt on top eventually gives way. All those years later, though, no one in the neighborhood remembers there was ever a mine shaft there at all.

“There are people who have been here 60 years, or born and raised in that house, and never knew there was a mine shaft in the backyard,” Malloy says. “There’s nobody left to remember it.”

Or, at this point, pay for the fix. The county agency that Malloy works for has a grant from the state to deal with the holes: they backfill them with mine waste, concrete and scrap steel. A small one might cost $1,000 to fix; a larger, deeper shaft can cost anywhere from $5,000 to $10,000 to remediate.

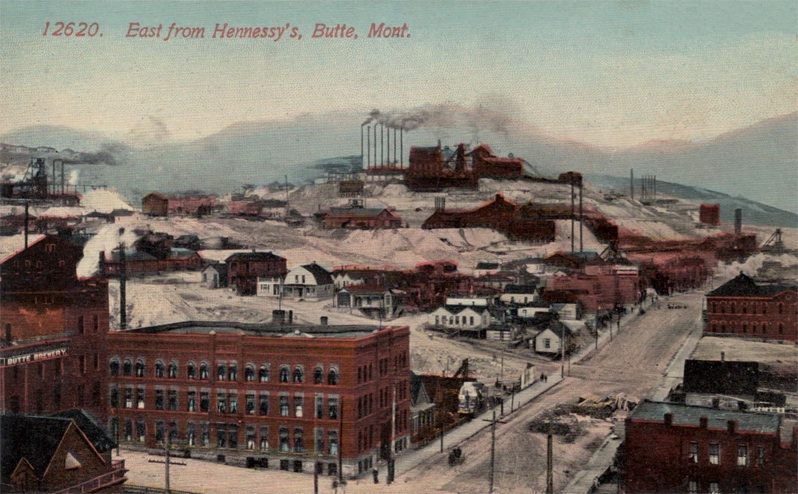

Butte in the 1910s. (Photo: Public domain)

Mining continued through World War I and II, and in the 1950s, companies started pit mining in the area. The toxic Berkeley Pit, one of the largest Superfund sites in the country, is in this city. Now, though, those mines are shut down. When the business began to dry up, so did the town’s population; only about a third of the 100,000 people remain from its peak as the site of world-scale production. “We’re still living with the remnants from that,” says Malloy.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook