In an Oklahoma Museum: All the Gory Details and Beetles of Skeleton Preparation

Bones in preparation (courtesy Skulls Unlimited)

Have you seen the ghost of Tom?

Long white bones with the skin all gone.

Po-oo-or Old Tom!

Wouldn’t it be chilly with no skin on?

This well-known childhood rhyme proposes a pretty thoughtful question that has to be answered with an affirmative: Yeah, it would be pretty chilly with your bony skeleton all exposed and no skin on.

At the Museum of Osteology in Oklahoma City, bones, skeletons, and skulls are the main attraction. Complete skeletons of every variety, from deer to dog, hawk to human, are on display. In fact, it’s known as “America’s only skeleton museum.” In of itself, this collection is surely unique. But that isn’t their only claim to fame, or even the most impressive attribute of the museum or the retail portion of the facility, which is called Skulls Unlimited, the “world’s leading supplier of osteological specimens.”

The reason I entered their rather non-descript building was to discover how they created a skeleton, or more accurately, the tedious, smelly, and strangely hypnotic process of stripping the skin away (and muscles, tendons, fat, and anything else that can be considered flesh) in order to get their “long white bones.”

courtesy Skulls Unlimited

courtesy Skulls Unlimited

Jay Villermarette began collecting skulls at the age of seven. The cranial portions of cats, dogs, cows, and deer were the first to join his collection. The skulls didn’t necessarily represent anything particularly morbid to Jay, but rather it gave him a chance to learn about the differences and similarities of all types of animals, including humans.

Many of the bone samples he collected from his backyard and beyond still had scraps of flesh clinging to it. He tried burning, boiling, and even using lye to get rid of the meat, with no method working particularly well. Then, Jay realized nature had it right all along. When animals die in the wild, the decomposition process includes insects enjoying a delicious meal. The hungriest, most effective, and efficient of these insects is the dermestid beetle, or as it is more commonly known, the skin beetle.

Dermestid beetles in action (courtesy Skulls Unlimited)

Dermestid beetles in action (courtesy Skulls Unlimited)

The dermestid beetle is indigenous to North America and commonly found under a rotting corpse, snacking away. Now, Jay had discovered not only the most efficient way of cleaning his skulls, but the most cost-effective.

Cleanings bones with beetles (photograph by Matt Blitz)

Cleanings bones with beetles (photograph by Matt Blitz)

In 1986, in his early twenties and during a time of unemployment, Jay decided to turn his passion into a business — Skulls Unlimited International Inc. He collected, prepared, and cleaned skeletons not only for his own research purposes, but for institutions, museums, and fellow collectors around the world.

Twenty-eight years later, Jay’s company is unlike any other, using hungry beetles to process samples. Skulls Unlimited now employes 23 fellow skeleton enthusiasts, along with Jay’s wife (who is the co-owner) and his four children, three sons and one daughter. Their clients include leading schools of osteology, independent researchers, and the Smithsonian. They have prepared and processed skeletons from practically every animal on Earth (yes, including humans), save for a panda, due to the restriction that when a panda dies, it must immediately get sent back to China.

courtesy Skulls Unlimited

courtesy Skulls Unlimited

I had the honor of a special “behind-the-scenes” tour of Skulls Unlimited by Josh Villemarette to see the stripping away of skin from full-fleshed animal to skeleton. It begins with some basic slicing and dicing, the technicians cutting the chunks of flesh off so the beetles can eat quicker.

Then, the bones go into the beetle tank. For, say, a dog skull, it can take less than 24 hours for the beetles to do their job. Sometimes, it can take longer. As Jay said to me as I was exploring, “If you had steak everyday, there would be some days where you were tired of steak. The beetles sometimes need to take a break.”

Bones & beetles (photograph by Matt Blitz)

Bones & beetles (photograph by Matt Blitz)

I was allowed to enter the beetle room with one warning from Josh, “It will smell in there. Since it is a Monday, it won’t be as bad as other days, but it will smell. In fact, be prepared, your clothes will smell the rest of the day as well.” He was right. It smelled. With thousands of bugs chomping at decomposing flesh, I guess it is only fair to have a rather poignant stench. As for my clothes, they did reek the rest of the day like, well, death. That night, I threw my second favorite pair of jeans out.

After their time with the beetles, the bones are dipped in a vat of liquid — the ingredients being a “trade secret.” Then, with a tad bit of scrubbing, the skulls are ready to go — either shipped out across the world or sold in their museum retail shop.

Bird skeletons (photograph by Matt Blitz)

Bird skeletons (photograph by Matt Blitz)

Before I left, I made sure to purchase a muskrat skull for my friend and fellow Obscura Society field agent Erin Johnson (she’s really into bones and all things taxidermy). As for my souvenir, I did not throw out the purple polo shirt I wore that day. It still smells like the rotting flesh peeled off from those long, white bones.

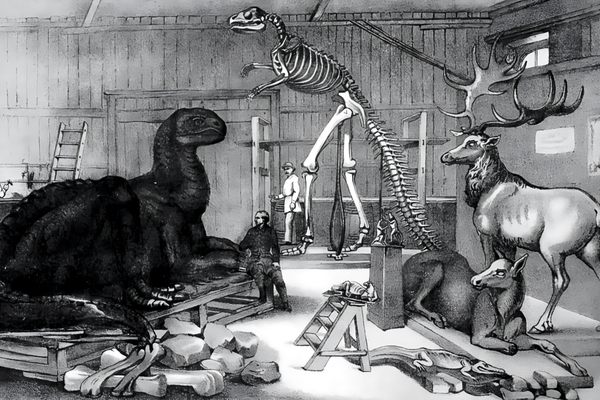

Articulating a skeleton (courtesy Skulls Unlimited)

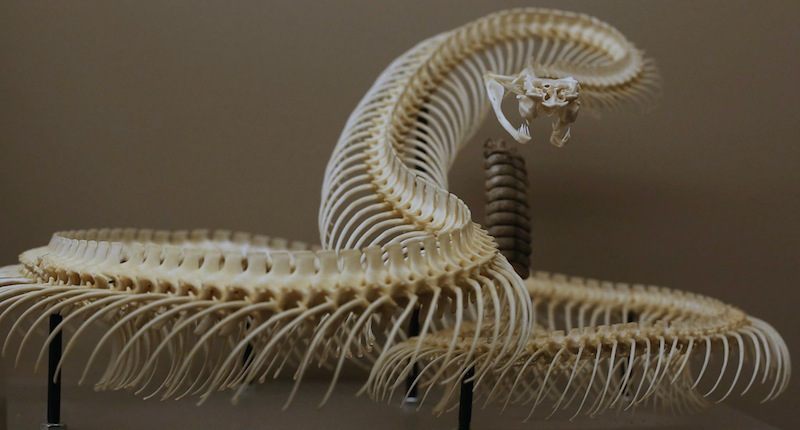

Snake skeleton (courtesy Skulls Unlimited)

Behind-the-scenes at Skulls Unlimited (photograph by Matt Blitz)

Killer Whale in the Museum of Osteology (courtesy Skulls Unlimited)

courtesy Skulls Unlimited

Museum of Osteology & Skulls Unlimited (photograph by Matt Blitz)

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook