When Royalty, Scientists, and Gardeners All Wanted Fake Fruit

One collection of fake produce is a reminder of both ingenuity and loss.

The city of Turin, in northern Italy, is famous for unusual museums, from the National Car Museum to a museum dedicated to personal finance. But hidden in one of the city’s iconic Baroque buildings lies a cultural oddity overlooked by most guidebooks. More than 1,100 life-size models of apples, pears, peaches, and grapes sit on display in two large rooms adorned with 19th-century frescoes.

Until recently, the resin and wax fruits were scattered around the Royal Station of Agricultural Chemistry, a research outpost run by the local government. When the Royal Station closed in the early 2000s, workers sorting through old books and equipment discovered the unusual artifacts, abandoned for almost a century.

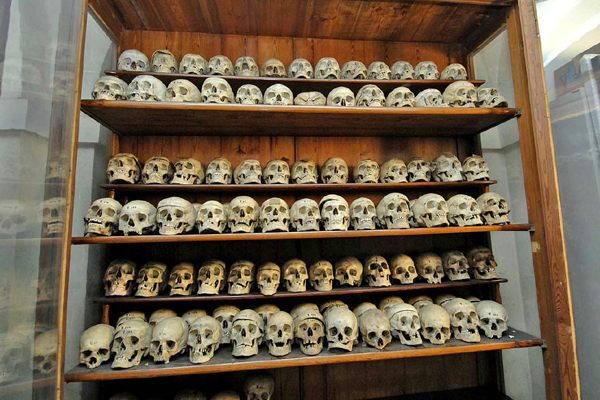

The models turned out to be the work of Francesco Garnier Valletti, an eclectic 19th-century artist and scientist. “We really had no idea that the fruits were there,” says Paola Costanzo, head of the curatorial team tasked by the municipal government to arrange the collection for display. There was so much material that it took 10 years for the Fruit Museum to open in 2007, inside the University of Turin’s Anatomical Studies Palace. Some fruits dominate the collection, with 494 types of pears, 286 types of apples, and 44 types of apricots on display. Their shiny skin, real stalks, and blemishes make them virtually indistinguishable from actual fruit.

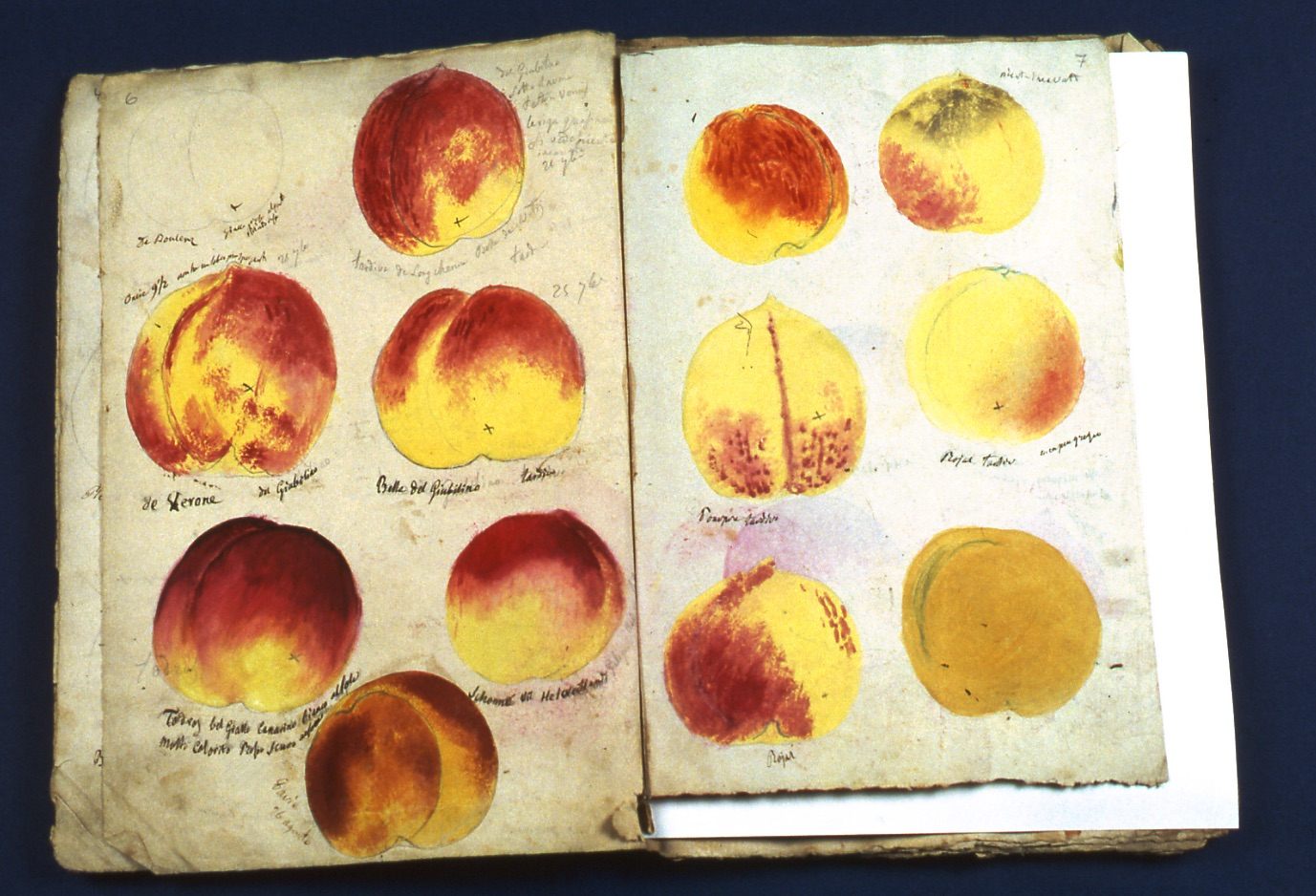

At first, Costanzo and her colleagues thought that the hyper-realistic produce served as a teaching aid for students. According to Jules Janick, a horticulture professor at Purdue University, botanical research relied on illustrations and wax models of fruit before the invention of photography. But after a dive into the dusty archives of the Royal Station, Costanzo and her team quickly dropped this initial assumption. From information stored in official letters, ancient invoices, and research bulletins, they pieced together that it wasn’t education that spurred Garnier Valletti to create hundreds of fake fruits. It was advertising.

Francesco Garnier Valletti was born in 1808 in Giaveno, a village near Turin. In his youth, he trained as a candy maker, specializing in sugared almonds and herbal sweets. By 1830, he had moved to Turin and expanded his craft to fake flowers and fruits. Local noblewomen enjoyed his wax and paper-mâché bouquets, and eventually his work came to the attention of the Austrian governor of Milan. It wasn’t long before he called Garnier Valletti to serve as the official modeller of the Austrian crown in Vienna.

As explained by Anne Odom in the book At the Tsar’s Table, many European royal families used elaborate tabletop decorations to showcase their wealth. Between the 16th and 19th centuries, families hired trained craftsmen to create centerpieces made of sugar, marzipan, or wax. Subjects went from flowers to fruits all the way to actual buildings—Odom cites a banquet in honor of Saint Peter the Great’s birth, which featured a stunning sugar model of the Kremlin. Russians were especially known for their displays of exotic plants and fruits, and soon Garnier Valletti’s skill was sought out by Tsar Nicholas I, who called him to his service in Saint Petersburg.

But political turmoil around Europe, coupled with his wife’s sudden illness, forced Garnier Valletti to go back to Turin in 1848. There he met Auguste Burdin, an entrepreneur from France who ran a successful plant delivery business. “Burdin was running an Amazon of seeds,” Costanzo explains. “He would showcase his plants in local greenhouses and ship seeds all over Europe.”

Burdin’s greenhouses featured in some of the earliest Turin travel guides and attracted clients from all over Europe. But the entrepreneur struggled with communicating the value of his plants to prospective clients. People often visited when only a few trees were in bloom, with only illustrations to communicate the full potential of each plant. When Burdin heard of Garnier Valletti’s work, he immediately saw the advertising potential of fake fruits that could be shown to clients year-round.

In 1853, Burdin commissioned Garnier Valletti to create an exhaustive inventory of more than 1,200 types of fruits and vegetables. For each type, Burdin demanded three identical life-size models. Garnier Valletti accepted the commission, but struggled with Burdin’s request for identical models. Throughout his fruit modeling career, he had produced faithful replicas of organic life. But he never found a way to make identical figurines. Until, one night, the ingenious artist envisioned a new technique.

As Costanzo explains, Garnier Valletti was a self-taught scientist with an all-encompassing sense of curiosity. Unlike many of his counterparts, he was interested in folk wisdom and traditional remedies. His 732-page book, Collection of All Kinds of Secrets, contains a long list of folk remedies, from a freckle-reducing concoction made with hen blood to a love potion. Perhaps because of his belief in the occult, Garnier Valletti attributed his greatest invention to a dream. An entry in his journal dated from March 5, 1858 reads: “Artificial fruits are to be made with alabaster powder mixed with wax, rosin and dammer resin … Discovery made on March 5 1858 during a nightdream.”

The “secret” consisted of creating a plaster mold of a piece of fruit, then pouring in a mix of melted wax, rosin, and dammer resin that was easy to model, compared with other kinds of wax. The plaster mold allowed for more than one figurine to be made for each fruit. Referencing sketches of each type of fruit, Garnier Valletti went the extra mile to add realistic detail. With a sprinkle of powdered wool, he recreated the downy skin of apricots and peaches. Thanks to a thin layer of crushed white stone, his fake grapes even gleam like a fresh-picked bunch. Plus, “his formula resulted in more durable models,” Costanzo explains, adding that only 38 fruits had to be restored before being displayed to the public. “And its aesthetic results are for all to see.”

Burdin was equally pleased with such an impressive collection. But a few years after receiving his innovative advertising catalogue, he went out of business. Garnier Valletti was left jobless, but kept making fake fruits and vegetables until his death in 1889. One of his most notable customers was Prince Henry of Orange, who commissioned 870 fruit models for the School of Agronomy in Amsterdam.

Burdin’s collection was first donated to the Agricultural Science faculty in Turin, and then used by a local peddler who toured rural farms to showcase wonders from the cities. Eventually, all the fake fruits were bought by Francesco Scurti, the director of the Royal Agricultural Station, where they remained until the early 2000s.

According to Costanzo, Scurti used the collection as three-dimensional catalog of local cultivars. Cataloguing local fruit varieties was part of the Royal Station’s mission, but Scurti was especially interested in testing each type of fruit against cold weather and ice. “Scurti was operating at a pivotal time in agricultural history,” Costanzo says. “Thanks to refrigeration, fruit could be preserved for months and travel to far-flung locations.” In order to master his knowledge about refrigeration, Scurti equipped the Royal Station with one of Italy’s first rudimentary fridges.

By the 1950s, refrigerators became a staple item across Italian households. But precisely because of this innovation, local biodiversity was lost. “Farmers used to keep many varieties of fruit to ensure produce across seasons,” Costanzo says. “Once fruit could be easily preserved through time, they opted for cultivars that were easier to grow and transport.”

Today, the local supermarkets offer three or four varieties of apples, compared with the nearly 300 modeled by Garnier Valletti. According to Valeria Fossa, a botanist that helped catalogue the collection in 2007, nearly 70 percent of the cultivars on display at the Fruit Museum have gone extinct. In the museum’s guestbook, visitors exclaim over the breadth of fruit types once common in the area. “This collection is many things at once,” Costanzo says. “It’s a work of art, a science document. But most of all it’s a historical memory to remind us of what’s lost.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook