A 45-Year-Old Mom and a Manson Girl Both Tried to Kill Gerald Ford

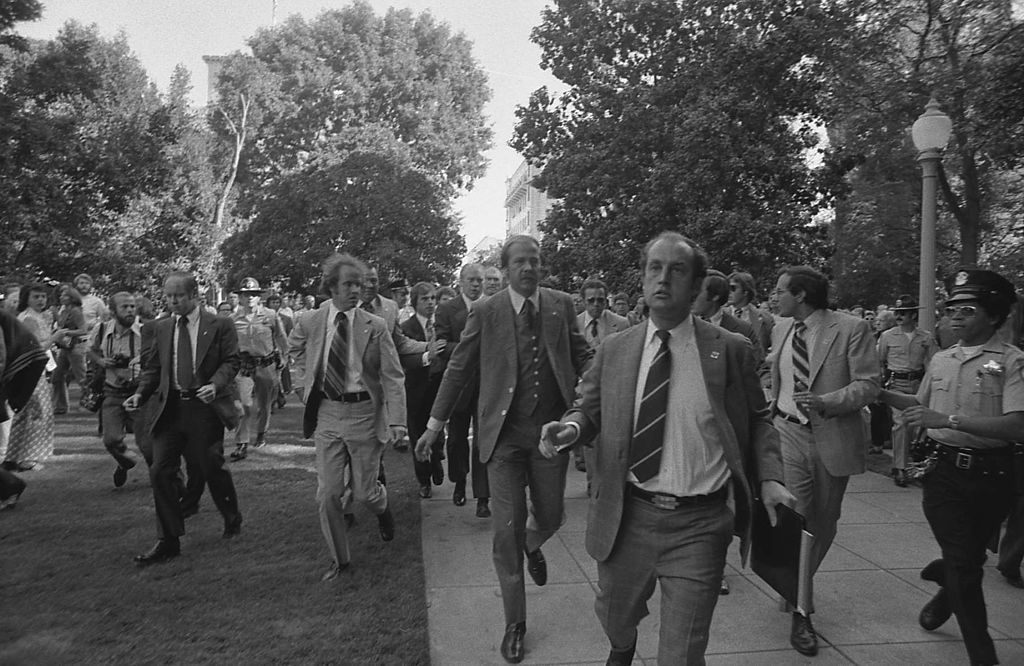

After Fromme’s Sept 5, 1975, attempted assassination (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

In September of 1975, Lynette “Squeaky” Fromme was on the front page of the New York Times: earlier that month, she had brandished a .45 caliber automatic pistol at President Gerald Ford, and now she had been judged competent to stand trial for the attempted assassination. Normally, this might have been above-the-fold news. But on that same day, the Times was profiling Sara Jane Moore—the other woman who had attempted to assassinate Gerald Ford that month.

It’s a historical fact that many forget: Two women attempted to assassinate Gerald Ford, in the same month.

Both attempts had occurred in California, Fromme’s in Sacramento, Moore’s in San Francisco. Fromme had not fired a shot; Moore had, and it went wide. The two attempts were not connected to each other, but both women had been involved in the strange subcultures of 1970s California.

Fromme, 26 at the time, was a member of the Manson Family, and although she had not been implicated in the group’s murders, she was one of Charlie Manson’s oldest and most devoted supporters. Moore was older, 45, and she had immersed herself in the world of San Francisco’s leftist political groups, in part out of a personal fascination and in part because the FBI had recruited her as an informant.

It’s hard to outmatch a Manson Family member in a contest of unsettling personalities. And Fromme holds the distinction of being the first woman charged with the attempted assassination of a U.S. president. But between Ford’s two would-be assassins, it’s Moore who, ultimately, is the more mysterious and troubling figure.

Fromme was a small, red-headed woman who, by 1975, had etched an “X” on her forehead in support of Manson and taken to wearing a red hood and cape. But, in a way, her story’s familiar enough. As reporter Jess Bravin recounts in Squeaky, his autobiography of Fromme, she grew up unhappy, in an abusive household. By high school she was inconsistently attending class, trying drugs and spending her time with older men. She was what we’d now call a cutter, and she tried to slit her wrists. When she left home and ended up on Venice Beach, she met a charismatic older man—Manson—who, for many years, made her life interesting and better than it ever had been. She remained loyal to him even after he started leading the people who gathered around him down a dark path; her defense, in her trial for the assassination attempt, was that she was not interested in hurting Ford but in attracting attention to Manson’s cause.

Moore seems like a more sympathetic character. Externally, she looked like an average member of American society. When she stood in the crowd while waiting to shoot the president, she was wearing “baggy tan pants and a neatly pressed blue raincoat,” the scholar Philip H. Melanson wrote in his history of the Secret Service—she dressed like a mom. And she was: She had four kids, which was normal enough in 1975. But only one of them still lived with her—the other three had been officially adopted by their grandmother, which would have been more unusual. She had also been married and divorced five times. Even if she dressed the part, she was not the picture of normalcy.

Born in West Virginia, Moore (a name she assumed after her fifth divorce) was always, as the reporter Geri Spieler writes in Taking Aim at the President, seen as someone who was a “little odd.” Her first two husbands were in the military; the second two worked in the film industry, one as a bookkeeper, the other as a sound engineer. Her fifth husband was a doctor: Moore lived with him in a staid San Francisco suburb and volunteered for the senate campaign of a Republican candidate.

After the divorce, Moore volunteered to work at People in Need, a feed-the-hungry organization that Randolph Hearst created to try to appease his daughter’s kidnapper. From the beginning, here too, she acted strangely. When she showed up, she told the people in charge that God had sent her; soon, she had forced her way into a role as PIN’s press person. The operations of PIN were dominated by leftist groups, but Moore maintained her mom uniform of blue slacks, a camel blazer, and a string of pearls, Spieler writes. She gained the trust of Hearst himself. But within PIN, she was known for swerving erratically between hyper-professionalism and irrational anger. She later became the organization’s bookkeeper.

However much she was enjoying her new life as a left-leaning activist, it seems that she pushed deeper into San Francisco’s political scene in part because the FBI asked her to. Her PIN activities caught the attention of agents, who recruited her as an informer: they asked her to start attending the meetings of various leftist groups, taking notes on who came, and befriending fractious elements. (She wasn’t paid for this work, but the bureau did pick up her expenses.) Moore, Spieler says, had a “chameleon ability to charm everyone she met,” and soon she was both informing on the radical groups to the FBI and confiding to the radicals she knew about the FBI’s interest in them. At one lefty hangout, she was even known as “the FBI Lady.”

One interpretation of Moore’s assassination attempt is that she had made a choice between the two sides—she had decided to throw her lot in with the leftists and wanted to demonstrate her allegiance. In the days before she shot at Ford, Moore called up the San Francisco Police Department and told the officers there she was considering a “test” of the president’s security system. They took away her gun; she bought another one, and with that gun in her car, sped through downtown in the hopes, she later said, of being apprehended. While she stood waiting to fire her shot, she was thinking about whether she’d be on time to pick up her son.

In contrast, Fromme, at least by her own account, had a clear motive for wanting to shoot Gerald Ford. “I just wanted to get some attention for a new trial for Charlie and the girls,” she’d tell reporters later. The chamber of the gun she used was empty—although there were more cartridges in the pistol’s clip and the Secret Service agent who stopped her said she was fumbling to load it.

Both Fromme and Moore were both judged psychologically sound enough to stand trial; Fromme defended herself. (Mostly, she tried to make political statements about environmental issues, which didn’t go over well with the judge.) Dr. Gustave Weiland, a psychiatrist who evaluated Moore, said that people like her “cannot be described as psychotic.” They were strange, yes, “seldom at ease with themselves,” and they had hard time making strong relationships. But on some level, Moore knew what she was doing.

What’s so unsettling about Moore is that it’s hard to reconcile the person she presents to the world with the person who decided to kill President Ford. “You look like someone’s grandmother,” Matt Lauer told her, in a 2009 interview, and he’s right. He asked Moore why she agreed to the interview, and she explained that “one gets tired of being thought of as a kook, a monster, an alien. I’m a human being.”

Just watching the interview, it’s hard not to sympathize with her. But she’s good at creating that impression. Before Spieler wrote her book, she spent years talking with and visiting Moore, informally. It was Moore’s idea that she write the book. But as soon as the process started, and Spieler made clear that Moore wouldn’t have control over who she talked to or what would go into the story, Moore cut her off: “I am no longer home to you,” she said, and never talked to Spieler again.

Once you know that Moore can turn on a dime, it’s hard to watch her and not feel uneasy. Fromme seems like the sort of person who might think it was a good idea to brandish a gun at a president. With Moore, you’re just left to wonder.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook