See the Aftermath of a Fireball Meteor Exploding Above the Clouds

Just 33 feet wide, with the power of 10 atomic bombs.

In December 2018, over the Bering Sea along eastern Russia’s Kamchatka Peninsula, a fireball meteor exploded with a force of more than 10 times that of the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima. The exploding meteor, or bolide, was the third most powerful recorded since 1900, and we should thank the stars that it streaked in over the water: In February 2013, an asteroid exploded over the Russian city of Chelyabinsk, shattering windows across over 200 square miles and injuring more than 1,600 people. (Thankfully, no deaths were attributed to the explosion.)

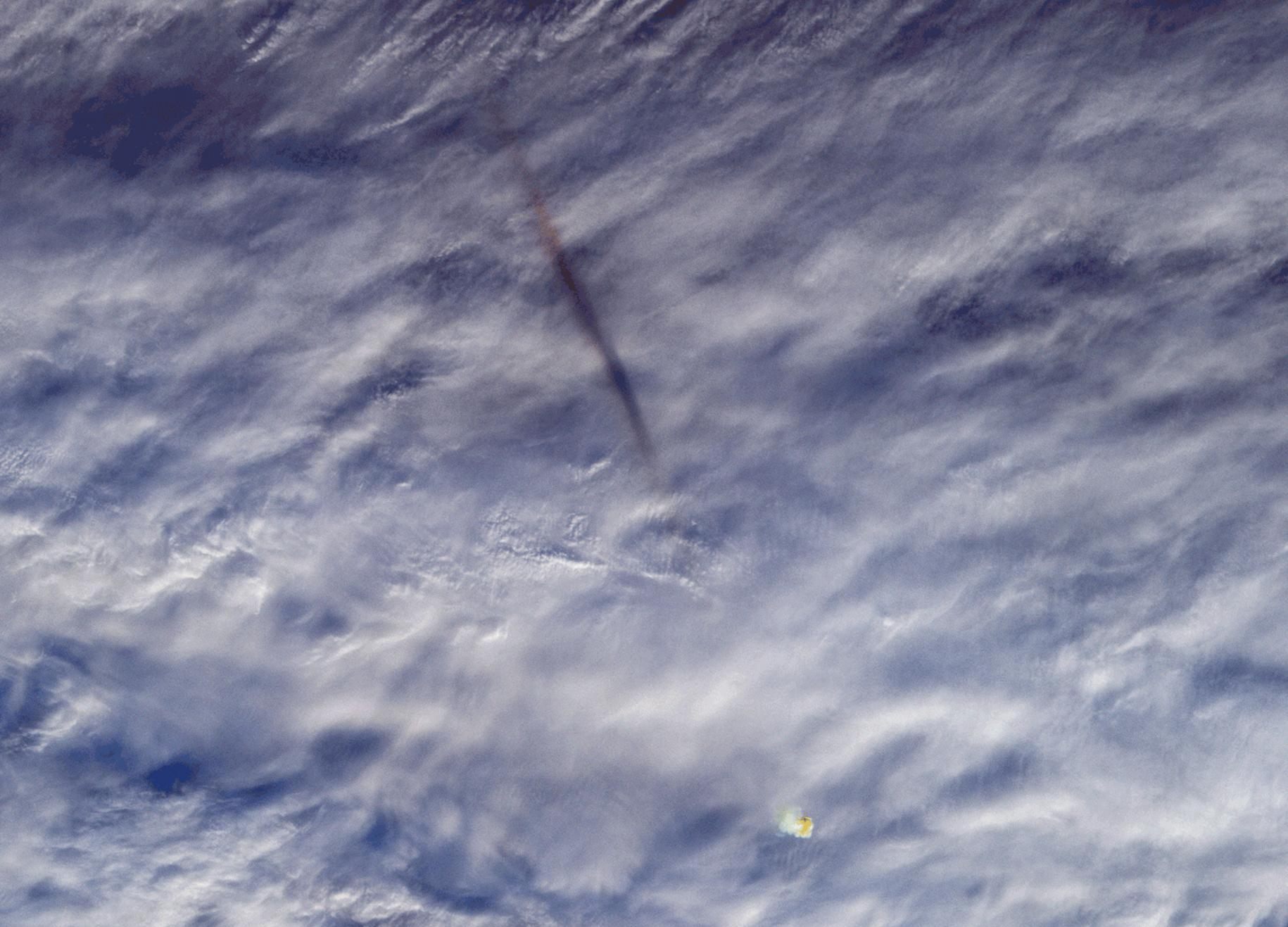

So, if a meteor explodes over the water and no one is there to see it, does it even make a blaze? That (among other things) is what NASA is for. Newly released images from the Terra satellite’s Multi-angle Imaging SpectroRadiometer (MISR) capture the view from above the clouds just minutes after the explosion took place. The shots capture the shadow of the meteor’s trail across the top of the clouds, as well as the burnt, glowing aura it left after cruising through the air at around 70,000 miles per hour. This animation contains images from five of the Terra MISR’s nine cameras:

According to ScienceAlert, meteor physicist Peter Brown of Western University, in Canada, has used the available data to measure the meteor’s diameter at about 33 feet, and its mass at about 1,400 tons. That places the meteor comfortably below NASA’s threshold for Near-Earth Objects (NEOs)—140 meters or about 460 feet—but the highly destructive Chelyabinsk asteroid was similarly small—itself only about 55 feet in diameter, according to Brown.

Fireballs—or meteors brighter in the sky than Venus—are actually not especially rare, and NASA has recorded 775 of them since April 15, 1988. As that map shows, they’re hardly exclusive to Russian airspace. But getting to see one relatively up close what happens just as it barrels through the atmosphere? That’s special.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook