The Brides ‘Imported’ to Colonial America for Their Brewing Skills

English colonists needed alcohol to survive. And for that, they needed women.

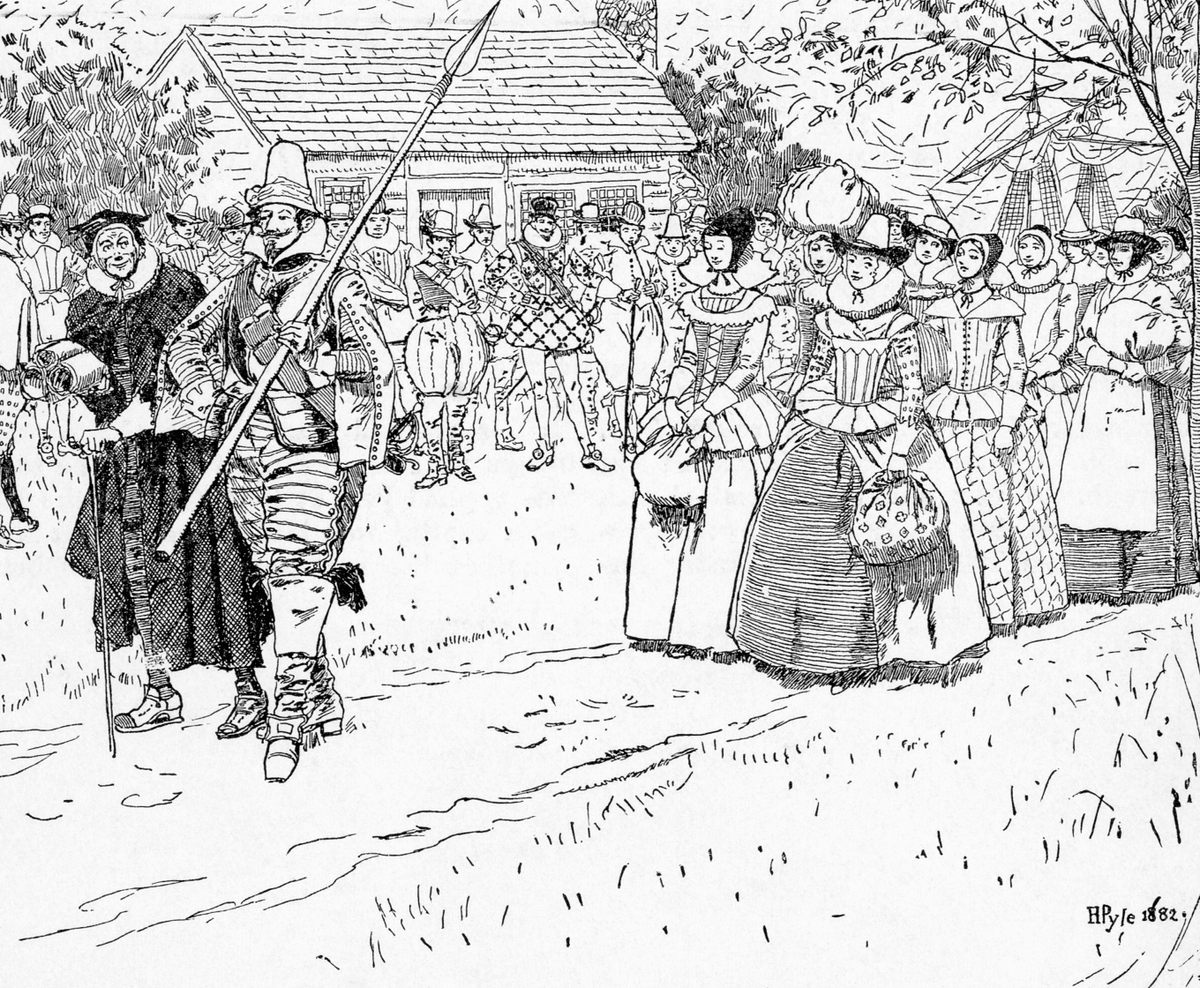

In 1621, Englishwoman Allice Burges stepped off a ship and onto American soil, clutching a letter that recommended her beer-making skills. She was one of 57 women “imported” from England by the Virginia Tobacco Company to join the early settlers of the Chesapeake Bay. The company’s investors had reasoned that wives and, eventually, children would cure the colonists’ loneliness and cement their attachment to the new land—and keeping the colonists happy was good for business. But the women also had practical skills that would improve everyone’s chances for survival.

An earlier attempt by the Virginia Tobacco Company to ship English brides to the settlers had not gone over well. The company “sent but few women thither [and] those corrupt,” complained one man. Another wrote that the first women sent over were “of so bad choice as made the Colony afraid to desire any others.” Historians have described those women as “vagrant children” and “abandoned waifs,” suggesting they had come to America because they had nowhere else to go and nothing to lose.

By contrast, Allice Burges and her peers came from well-off families. They were the daughters of artisans and gentry; a few were even related to knights. Like Burges, they all carried letters of recommendation that vouched for their “good bringing up” and their skills in “huswifery”; that is, chores such as brewing, baking, spinning, sewing, and making butter and cheese. But many were young widows or orphans, or “lacked what their contemporaries regarded as natural defenders,” writes historian David R. Ransome. Some of the women may have been motivated to emigrate out of a desire for a “natural defender”; others may have been chasing adventure. Whatever their reasons for coming to America, the women had been recruited by the Virginia Tobacco Company partly because they possessed skills that the male settlers—their soon-to-be husbands—lacked.

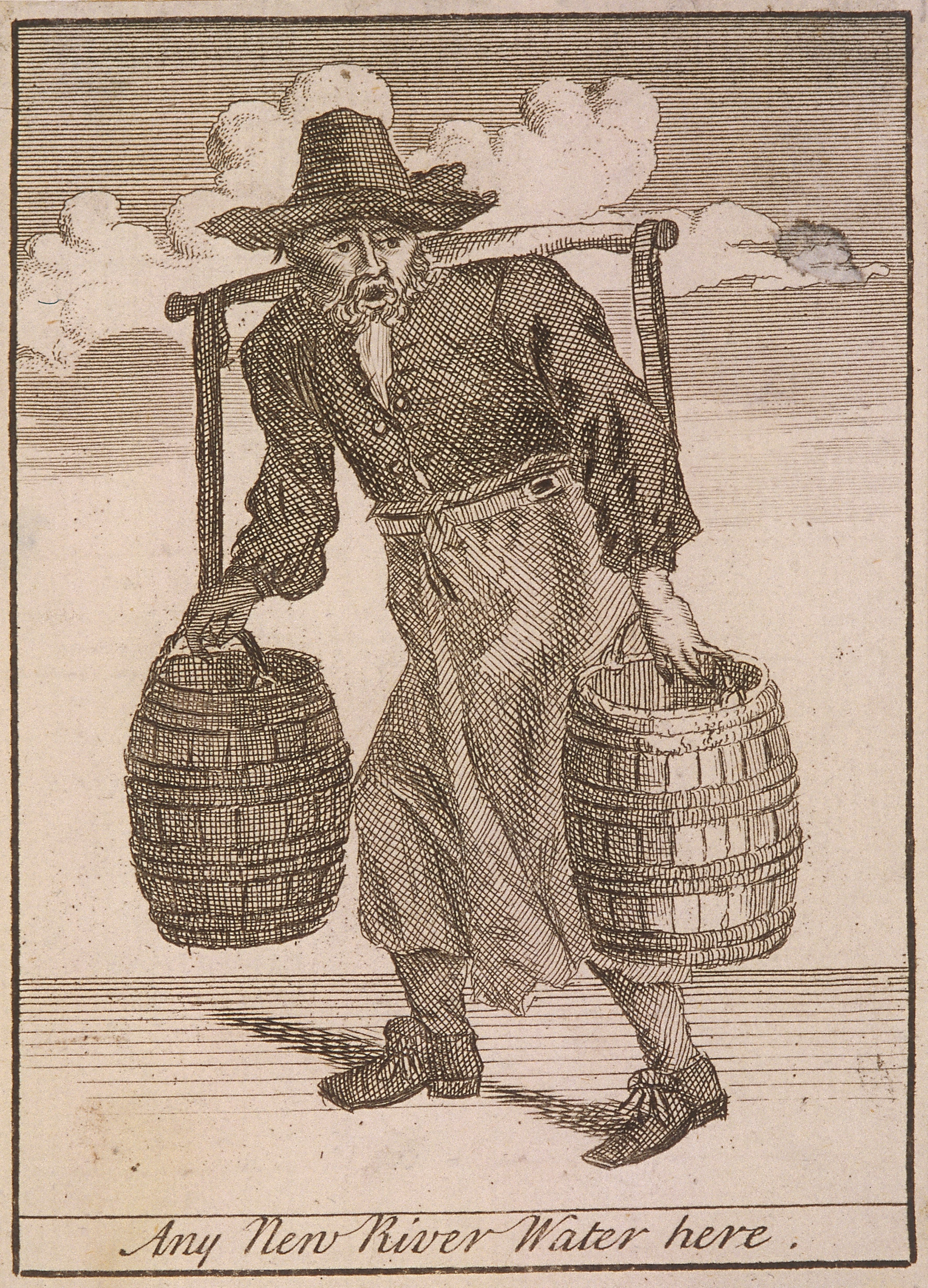

Making alcohol was one of the most critical skills the women were expected to perform. Besides the fact that the English colonists came from a culture of heavy drinking, there was nothing else to drink in the early settlements. Tea and coffee were rare luxuries, milk required keeping a cow, and fresh water was easily contaminated, especially the tidal waters of the Chesapeake. Colonists were so leery of their water that signs were sometimes posted at water pumps with the warning “Death to him who drinks quickly.”

The colonists’ distrust of water was also inherited from England, where waterways, particularly in urban areas, were often polluted with refuse and blood from butchered animals.

“Alcohol was safer [to drink] than water,” says Theresa McCulla, curator of the American Brewing History Initiative at the National Museum of American History. “The production of alcohol involved boiling, which would get rid of various pathogens … but there was also the fact that these societies considered beer and distilled spirits and other alcoholic beverages to be really nutritional. They were elements of the diet that provided sustenance above and beyond water.”

The English also simply didn’t enjoy the taste of water, and drinking it was considered a sign of poverty. An Englishman of means would down a pint or two of hard cider with each meal, and consume other alcohol as it chanced to come his way throughout the day.

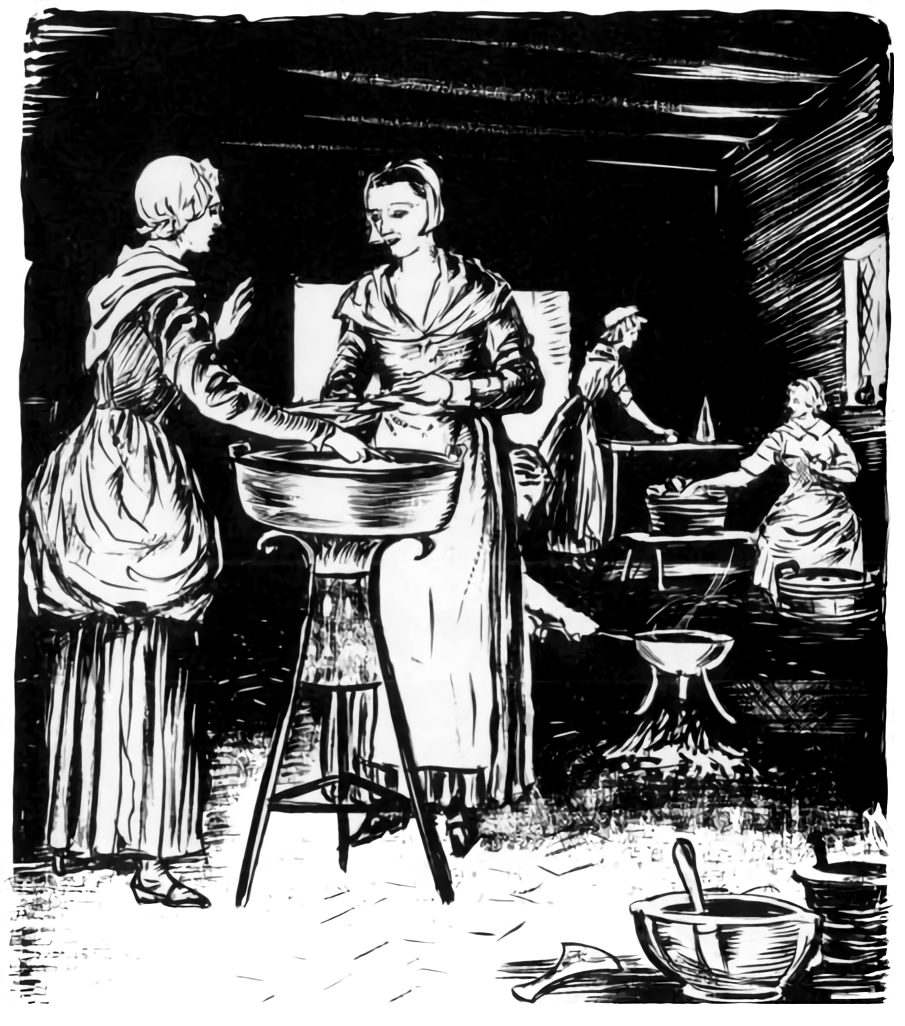

The first male colonists would have continued this tradition of eschewing water for alcohol, except for one problem: They didn’t know how to make it. Brewing, cidering, and distilling was all considered women’s work—or the work of domestic laborers and enslaved people.

“Brewing was very much a household chore,” says McCulla. “In England and other societies, brewing was the domain of women and other domestic workers until it became a profitable profession.”

Englishwomen made a variety of alcoholic beverages, including beer, cider, mead, ale, brandy, and whiskey, in their own kitchens, ensuring a steady flow of drink for their husbands and children. (No age was too young to imbibe.) In the colonies, men tired (and scared) of drinking water deliberately sought out wives who could whip up safer, more interesting elixirs.

But despite the brides imported by the Virginia Tobacco Company, women were still so scarce in the colonies in the 1600s that many men were “reduced” to drinking water. The Chesapeake in particular was known as a “colony of water drinkers,” writes historian Sarah Hand Meacham in her book Every Home a Distillery: Alcohol, Gender, and Technology in the Colonial Chesapeake.

In 1656, an English traveler named John Hammond complained that in some parts of Virginia and Maryland, nothing but water and milk was available. He blamed the few “goodwives” there, calling them “negligent and idle” because they didn’t produce enough alcohol. He hoped his observations, made public, would “shame them out of those humors” and light a fire under their kettles. “They will be adjudged by their drinke, what kind of house-wives they are,” he warned.

But Hammond’s expectations were probably unreasonable.

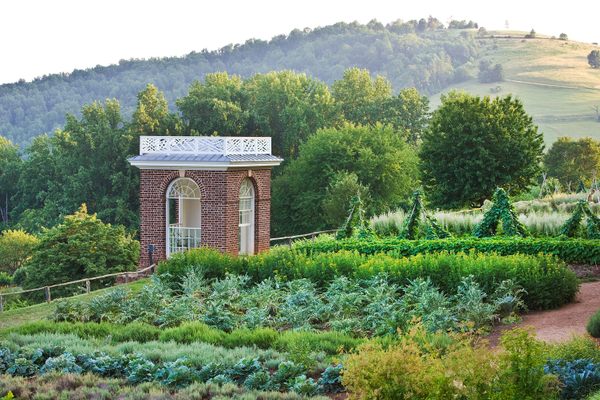

“It was impossible for Englishwomen to recreate the alcoholic beverages that men, women, and children drank daily in England when they first landed in Jamestown,” Meacham writes in an email. “They couldn’t yet grow the wheat or hops to make the ale and beer that were increasingly common in England. Even if they had them, it was too hot to make ale or beer a real option in the American South before refrigeration and pasteurization. As for cider, Virginia did not have the same apple varieties as they did in England. And distilling technology was large, expensive, and liable to explode. As a result, colonists just had to be flexible and drink quick ciders made from local fruit trees in the early years.”

Making cider also kept precious food from going to waste.

Before the era of mechanical refrigeration, people had to be resourceful in how they preserved their food and drink,” says McCulla. “Perhaps it’s pickling, perhaps it’s drying, perhaps it’s baking or cooking or keeping something in a cool place, a cellar. But for things like pears, apples, and peaches, a perfect way to preserve those things was to make cider, to make perry out of pears, to make distilled spirits out of fruit and grains.”

Women became creative in finding substitutes for the staple ingredients of beer and ale. They often used spruce essence in place of hops, which lent a similar bitterness and acted as a preservative in the way hops did. They also sometimes used ground ivy, a common weed. Instead of barley (a key source of fermentable sugars), women substituted fruits and vegetables. Unhopped ale brewed from corn, pumpkins, persimmons, or molasses was a common beverage in colonial Chesapeake households.

McCulla rattles off a list of other common ingredients from colonial-era beer recipes: ginger root, sage, sweet fern, wheat bran, rye meal, toasted bread … “They were certainly working with things that were available to them in their local environment,” she says.

As the colonies’ female and enslaved populations increased, so did home-scale alcohol production. Soon women were abundantly supplying their families with alcohol. By 1770, the average adult white male drank the equivalent of seven shots of rum per day, and the average adult white woman drank almost two pints of hard cider a day. No longer a colony of water drinkers, “The Chesapeake was drenched in alcohol,” Meacham writes in Every Home a Distillery.

Women homebrewers continued to experiment with all kinds of weeds, shrubs, herbs, fruits, and grains to make beer, ale, and cider, as well as invent beverages such as “cherry bounce” and “flip.” The sheer diversity of early American beers speaks to the creativity of those women, recruited and valued for their scrappiness in the kitchen.

But gradually brewing became a commercialized activity, which meant that women were excluded from it. (“When money got involved, men increasingly started brewing,” historian Gregg Smith told Craft Beer & Brewing magazine in 2016.) Industrialization also meant homogenization, and the unique brews that early women colonists created all but vanished. That is, until the modern craft beer movement developed a taste for history.

Today’s breweries are recreating early American beverages such as spruce beer and flip. Some are aided by the original brewsters themselves. “Women copied lots of recipes for making alcoholic beverages,” Meacham writes in an email. “They also carefully preserved and passed down cookbooks in which the first third of the recipes were for alcoholic drinks.” (Although the recipes’ authors tended to be white women, it’s possible that their servants or slaves, if they had them, would have helped develop the recipes.)

This year marks 400 years after Allice Burges and her peers arrived in America. What better way to acknowledge their role—and perhaps the role of those “abandoned waifs”—in shaping American brewing than by recreating and enjoying their recipes?

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook