A Tanker Just Made It Across the Arctic With No Icebreaker for the First Time

A real conversation-starter.

On August 17th, a Russian tanker called the Christophe de Margerie pulled into South Korea’s port of Boryeong. The tanker, which is owned by the Russian shipping company Sovcomflot, had set out from Norway just nineteen days prior, meaning that it covered the 2,193-nautical-mile journey in record time.

Das russische Tankschiff Christophe de Margerie hat als erstes die #Nordostpassage ohne Begleitung eines Eisbrechers passiert.#klimawandel pic.twitter.com/hWYrzAYMy0

— sundine (@evasundin1) August 28, 2017

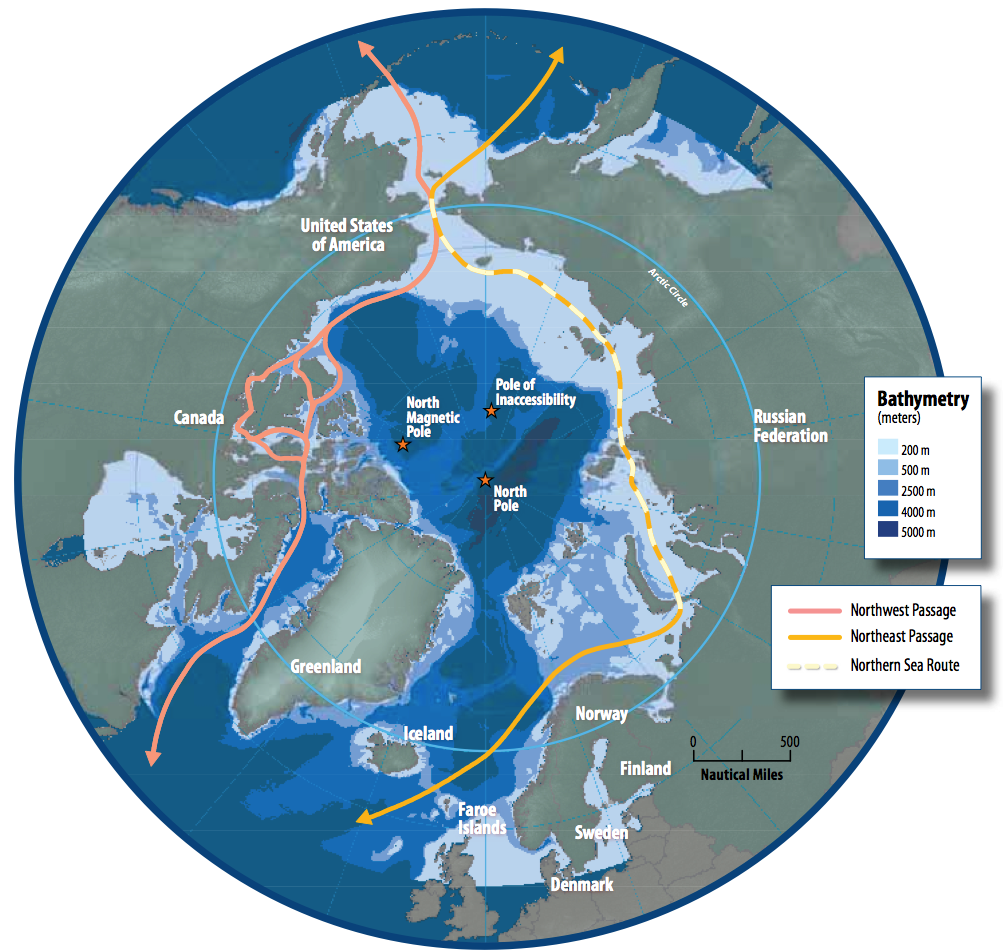

Even more unusual? It did it alone. As the New York Times reports, with this voyage, the tanker “became the first ship to complete the so called-Northern Sea Route without the aid of specialized ice-breaking vessels.”

As the Times writes, the Northern Sea Route, which runs along Russia’s Arctic coast, is more geographically direct than the most popular current route between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, which runs through the Suez Canal.

Logistically, though, it’s much tougher, as the sea there is covered with a thick layer of ice for much of the year. This has stymied would-be explorers, traders, and conquerers for centuries, ever since John Cabot set out to find a route from England to Asia in 1497. (Although Cabot thought he managed it, he had actually ended up in Canada.)

Since the end of the 19th century, shipping vessels have relied on special reinforced boats called icebreakers to help them get through the frozen waters—and only then in the summer, when the ice is thinnest. (The first, the Yermak, shepherded its first ship through the Arctic in 1897.) The Christophe de Margerie is currently the only tanker of its specific type to have this capability built-in: according to the BBC, it can get through ice up to 2.1 meters thick all on its own.

Sovcomflot expects this will be enough to let it make the journey for half the year, from July through December. Since the 1980s, minimum Arctic sea ice coverage, which occurs in September, has shrunk by about 13 percent every decade, one way in which climate change is reshaping the region. Maximum coverage, which happens in March, has also declined.

With our past track feature, see the Christophe de Margerie sailing through the arctic without an icebreaker’s help! https://t.co/vKxuu1yQEz pic.twitter.com/TUJcVHFxoX

— MarineTraffic (@MarineTraffic) August 28, 2017

Sovcomflot is banking on this trend continuing, and plans to make an entire fleet of icebreaking ships. “There is an assumption that the ice is not going to thicken dramatically for the economic life of these vessels, which could be over 30 years,” Bill Spears of Sovcomflot told the BBC. Like the Christophe de Margerie, all will carry liquified natural gas, almost as if to help themselves along.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook