The Centuries-Old Mystery of How Florida Got Its Flamingos

How did these statuesque birds get to the peninsula, and where did they go?

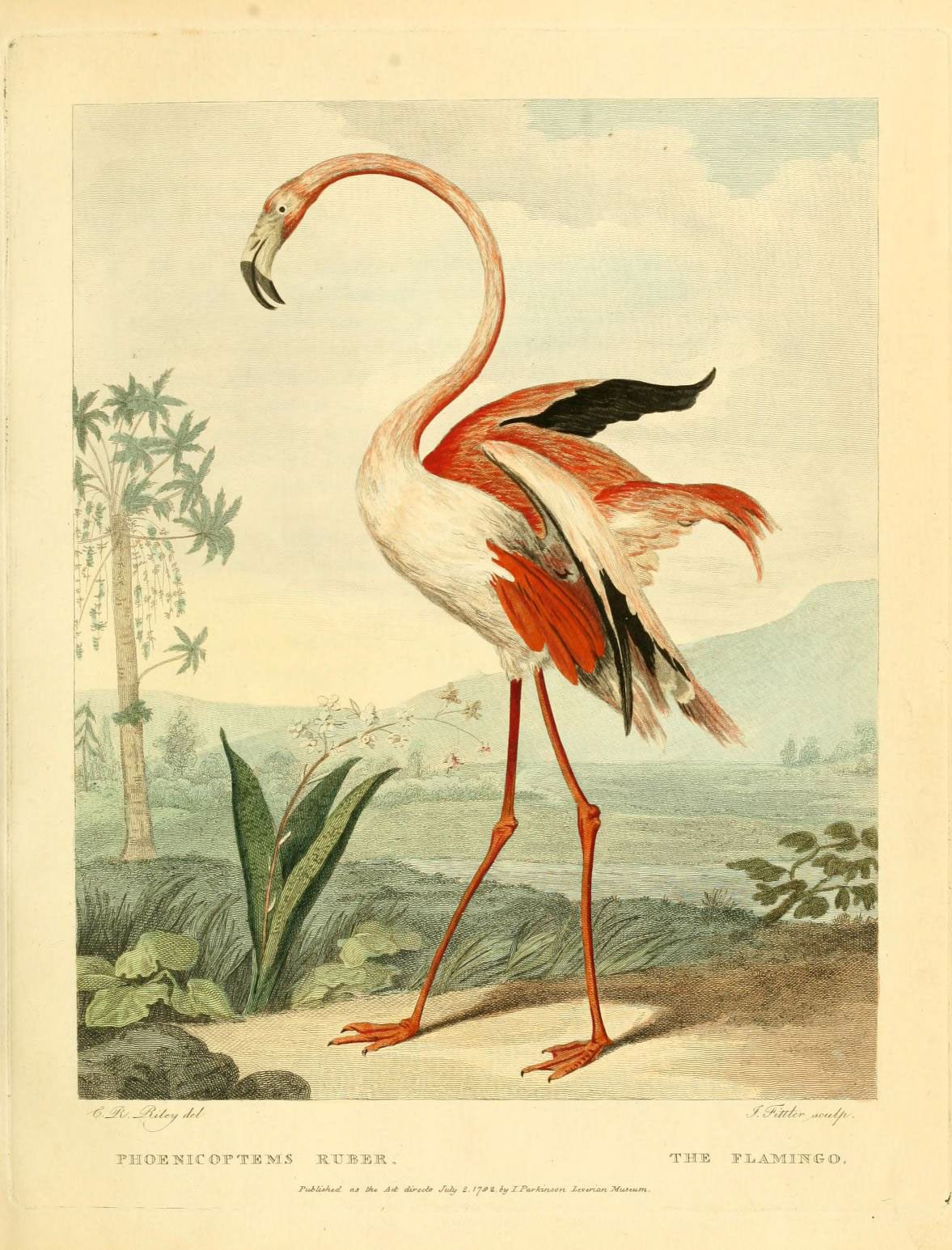

It was late afternoon, and John J. Audubon still hadn’t found a flamingo. The sun was slinking toward the horizon, the sky scuffed by wispy clouds, and the boat was able to slice through the water with barely a ripple. Not a bad voyage, but Audubon had engineered this expedition to the islands off of Florida’s southeast coast for the express purpose of finding a flock of the long-necked crimson beauties. Where were they?

Audubon had seen an American Flamingo (Phoenicopterus ruber) in Florida before—in Key West, soaring toward a hammock of mangroves. (Naturally, he tried to nab it as a specimen, but it dodged the shot he fired.) He knew that flamingos were thick in Cuba, and had heard that the birds often congregated near Pensacola, and sometimes Alabama or South Carolina. Now, in May of 1832, he was desperate to shoot one, or even lay eyes on one—but so far, no luck.

Then, off in the distance, he spotted a flock careening with outstretched wings, elongated necks, and legs tucked back behind them. “Ah! reader, could you but know the emotions that then agitated my breast!” he later wrote. The birds changed direction before he could aim his gun, but Audubon watched them as if entranced, and didn’t tear his gaze away until dusk settled.

The flamingo isn’t the state bird of Florida—that honor goes to the much-less-leggy Northern mockingbird—but the rosy-hued waders with Modigliani necks are deeply associated with the Sunshine State. When Audubon set out to a find a Florida flock, he described his desire to study “these lovely birds in their own beautiful islands.” In 1909, a rail line linking the southern state with New York adopted the moniker, christening itself after “the bird which is so typical of Florida.” Across the peninsula, a brood of contemporary waterparks, motels, and inns all borrow from the bird.

“Living in Florida, you see flamingos everywhere—in advertising, in place names, even on the logo for the state lottery—but as an actual organism, as a species, there was essentially no information available on the biology of flamingos,” said Steven Whitfield, a conservation ecologist at Zoo Miami. The birds are iconic, Whitfield says, but there’s been little information about their past and present in the state. When and how did they get to the region? What happened to them once they arrived?

The murky history spans centuries. While some 19th-century naturalists recounted dense clusters of flamingos around Florida, others were less certain about the birds’ primary strutting grounds. In the 1881 edition of his encyclopedic book, The Birds of Eastern North America, Charles Johnson Maynard notes that flamingos were rare in the Florida Keys. In fact, he wasn’t sure how plentiful they’d ever been there. Word had it that they clustered in the Keys in the summer months, while they molted—but he’d never seen one there himself.

At the turn of the 20th century, naturalists who wanted to get a close-up look at flamingos often traveled to the Bahamas to do so. In the 1896 revision to his book, Maynard describes an often-unpleasant excursion in a flat-bottomed bateau. The sun blazed off of the water and the light-colored mud just a few inches beneath it. To get a closer look at a flock, Maynard waded through three creeks, in muck that reached up to his armpits. “But what did that matter!” he concluded later. It all seemed worth it when he saw the birds arranged in an “immense flock” that “honk[ed] hoarsely.”

It was love at first sight. “Minor affairs were forgotten in the magnificent spectacle before us,” Maynard wrote. He left with a live specimen, which he named Aurora. She became a pet, dining on boiled rice and water-soaked bread, and trailing Maynard around the house. She hung around while he worked, and appeared to get along with Spottie, his dog—though she occasionally nipped the canine’s ear to nudge him out of the way when she wanted to pass.

In 1920, spurred by fears that American Flamingos were tiptoeing toward extinction, a gaggle of researchers from the National Geographic Society, Miami Aquarium Association, and other institutions headed to the salt swamps of Andros Island, in the Bahamas, to “hunt with a camera” and capture photographs of the birds. With the help of a local guide—Peter Bannister, who had also accompanied a similar outing in 1901—they traveled by yacht, canoe, and foot. They slogged through waist-deep water and sucking mud, juggling camera equipment in one hand and swatting at “blinding swarms” of mosquitoes with the other.

The trip was front-page news back in Florida. The Miami Daily Metropolis breathlessly chronicled the team’s escapades, quoting one member of the party who described the flock as “a flaming mass of brilliant scarlet bodies, jet black beneath the huge wings, with their long, slender necks gracefully lowering and raising their Roman-nosed heads.” The group spent 10 days hunkered down in blinds, shooting thousands of feet of film. Some members of the crew embarked on another outing a few months later, with the goal of capturing a live specimen to bring back to Miami and house near the beach in a spectacularly sun-drenched iron-and-wire cage larger than any other. That trek didn’t go to plan. They paddled 250 miles in canoes, but didn’t find the feathered treasure. The aquarium director, apparently dejected, explained it thusly: “This time, we didn’t find the fledglings we were after, nor did we locate the adult flamingo. They had disappeared.” The birds that had once been said to flock to Florida’s shores were getting harder and harder to find.

Whitfield, the ecologist, and a gaggle of collaborators try to pin down some specifics about Florida’s flamingos in a new report, published this week in The Condor: Ornithological Applications. To track the birds’ historic numbers and locations, the researchers surveyed the records of early naturalists, including Maynard and Audubon. They also excavated evidence from museum records, as well as more recent data from citizen scientists.

In the 19th- and early-20th centuries, the authors report, naturalists documented flamingo sightings in a number of Florida locations, including the Anclote Keys, Indian Key, Key Largo, and areas close to Cape Sable, Marco Island, and Miami. Eggs held by four museums, including the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History, and Harvard University’s Museum of Comparative Zoology, suggest that flamingos were nesting in the state in the late 1800s. The eggs at Yale are paired with a card stating they were collected in the Florida Keys in June 1884, and are scribbled with the inscription “585,” the number for American Flamingos on an 1880 checklist of American birds.

Museum records aren’t always reliable, the authors caution: None of these are accompanied by detailed field notes, and labeling can be inconsistent or even fraudulent. On the other hand, it’s not surprising that more eggs didn’t end up in museum collections, the authors add, because expeditions to nests were wildly inconvenient—eggs were incubated in salt flats that were far from roads and frustratingly shallow for boats. The collection dates on the labels do line up with known nesting seasons for flamingos in the Bahamas and Cuba.

On the whole, the authors conclude, “there is overwhelming evidence both from narrative accounts and from museum records that American Flamingos occurred naturally in large flocks in Florida.” These flocks were regularly 500 to 1,000 birds strong, and sometimes topped 2,500 members. Flamingos were hunted in large numbers for their plumes, skin, and meat, and the historical population was nearly wiped out by 1900.

Sightings were sparse for decades. Then, drawing on citizen science data, the authors mark an increase of wild flamingos spotted in the state between 1950 and 2017, particularly in the Florida Keys. Still, the picture isn’t entirely rosy: The population has never quite returned to a healthy state.

“We do, sort of, have flamingos, but we don’t have the resident breeding population that we used to,” Whitfield says. “Individuals fly in from the Bahamas or Cuba, forage a little while, and leave.” While there were once clusters of thousands of birds, Whitfield says, “we’re nowhere near that now.” The largest recent sighting was 150 individuals, and they didn’t hang around very long.

The research helps resolve a debate about whether the birds people spot today are wild or escaped from zoos or captive populations at tourist attractions. “Until just a few years ago, everyone thought that they were all escaped,” Whitfield says. It’s unclear how many trek back and forth between Florida and the Caribbean, and a better picture could emerge with the help of satellite images, banding, or population genetics.

This isn’t perfect data, the researchers admit: Some birds were likely counted more than once, and the figures would benefit from a mark-recapture technique. Still, Felicity Arengo, associate director of the Center for Biodiversity and Conservation at the American Museum of Natural History, thinks the work holds water. “The authors are cautious and recognize the limitations of the data in their study, but they provide ample evidence that Florida was the northernmost extent of the American Flamingo prior to the early 1900s and that populations have been recovering,” said Arengo in a statement.

Getting a grasp on the American Flamingo’s history and present is an important part of devising a strategy for protecting them, the authors write. Some agencies have classified the birds as nonnative species, rendering them ineligible for protection under wildlife laws. In Florida, where roughly half of the species are introduced and the other half are threatened, Whitfield says, “it’s a bit of an ecological mess.” He doubts any of the legions of introduced species—from Burmese pythons to primates and a handful of parrots—are a direct threat to flamingos, but the birds already face other challenges. Coastal construction can encroach on habitats, for instance, and hurricanes and storm surges can imperil low-lying nests.

The authors leave the business of policy recommendations to state and federal officials, but Whitfield points to a trend across the Caribbean, where flamingos are settling down again in areas where they had historically nested. “If protected, they may recover naturally,” Whitfield says. That could be key to a bright future for the strangely statuesque bird, the authors write—a “lost Florida icon” found and safeguarded.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook