Food Testing in 1902 Featured a Bow Tie-Clad ‘Poison Squad’ Eating Plates of Acid

Why the FDA owes its existence to 12 men eating poisoned meals.

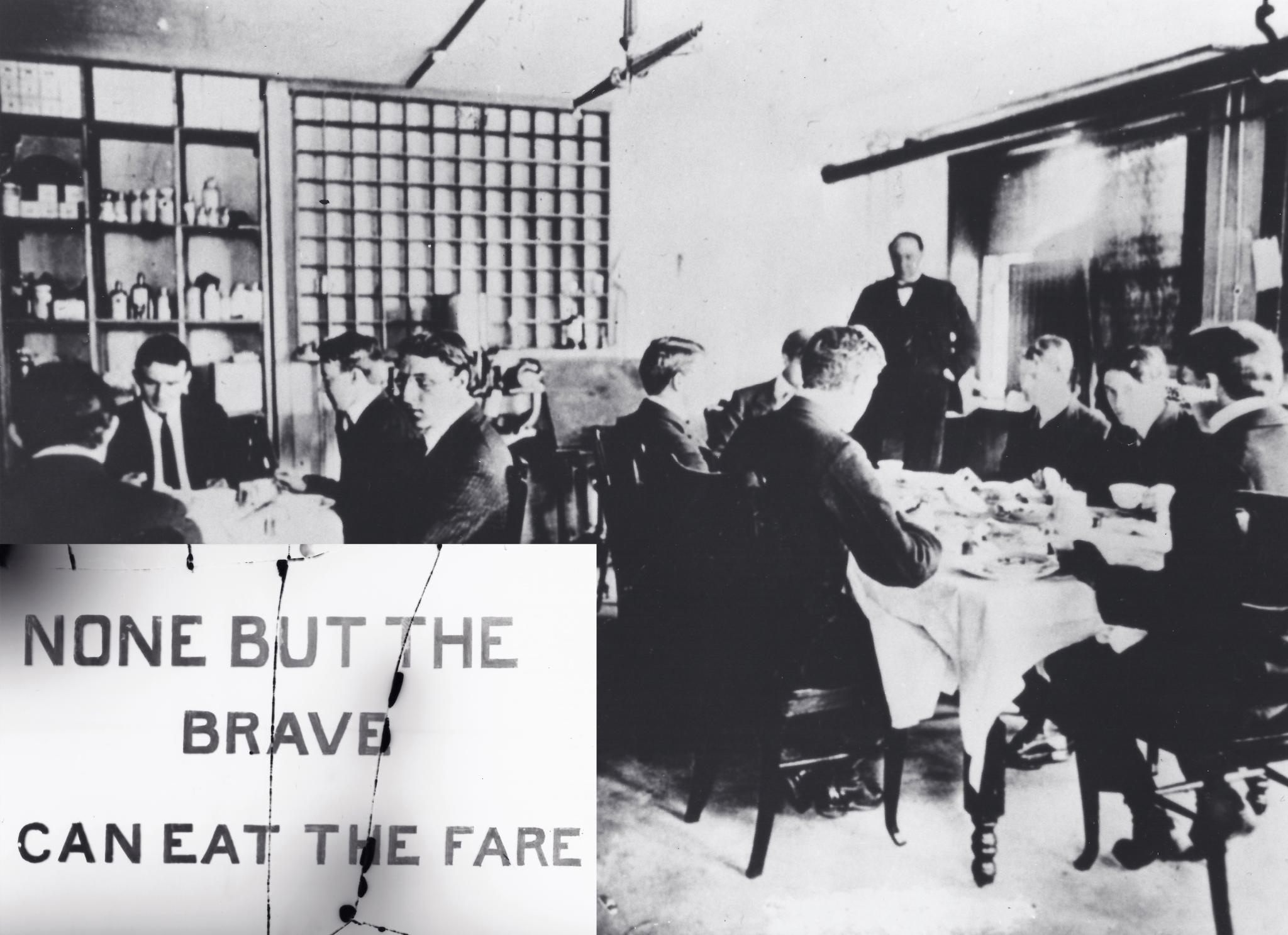

Members of the “Poison Squad”, individuals who tested whether food was safe for human consumption. (Photo: FDA/Public Domain)

Twelve young men sat around a fine dinner table with a crisp white tablecloth and silver settings. The collars of their pressed suits were neatly starched and their bow ties rested politely at their chins as they delicately brought forkfuls of delicious foods to their mouths, each morsel laced with formaldehyde and benzoate. Borax tablets polished off the meal.

These men were the Poison Squad: for five years, beginning in 1902, their nightly meals came from a government-run kitchen, where they ingested common—and previously untested—food preservatives. This danger-facing squad was not only responsible for proving a need for ingredient lists on food labels, but they propelled the creation of our modern Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

The act of healthy men boldly eating poisoned food on purpose lent the Poison Squad near-hero status. Their motto was “Only the Brave Dare Eat The Fare,” and the squad even had its own catchy rhyme, courtesy of poet S.W. Gillian:

On prussic acid we break our fast

We lunch on morphine stew

We dine with a matchhead consummé

Drink carbolic acid brew

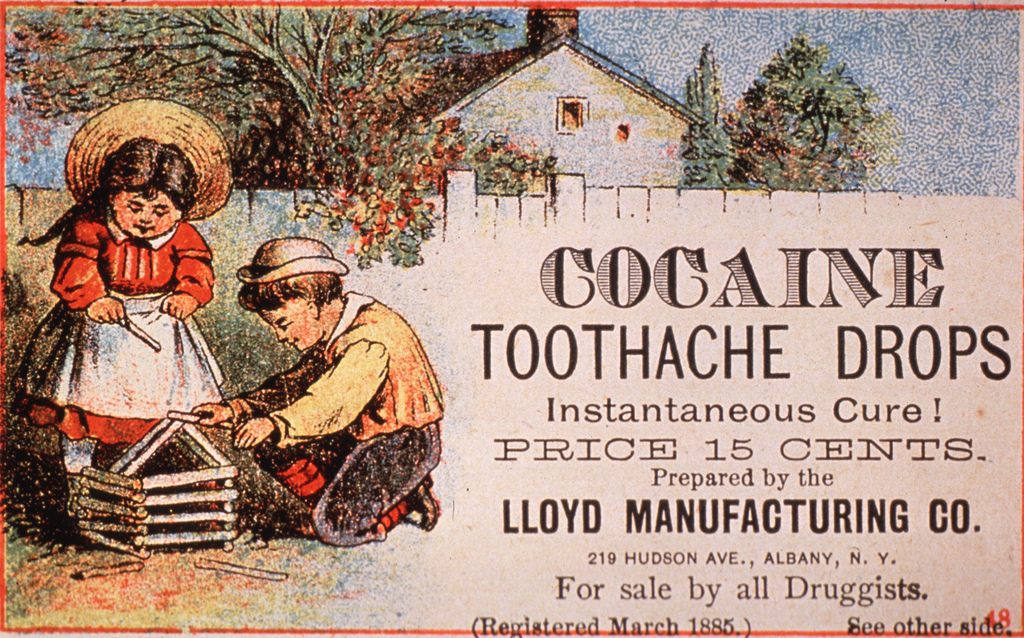

An advertisement for cocaine toothache drops, late 1800s. (Photo: National Library of Medicine/Public Domain)

Today, the idea of having a group of people willingly poison themselves seems unimaginable. But Harvey Wiley, chief chemist of the Bureau of Chemistry, felt he had good reason to go to this extreme when he started the experiment. Since the 1800s, the public had eaten dangerous, unregulated foods; “bitter beer” was laced with strychnine, and it was common to unknowingly eat chalk-filled bread. Wiley even caught honey companies passing glucose off as pure honey.

At the time, food safety was under the purview of state and local governments, but as the United States transitioned from an agricultural society to an urban one, local food laws started to miss the mark. More food products were being made in factories using new, untested chemicals as preservatives, without stating so on the label. Wiley wondered if all those new preservatives, which included borax, salicylic acid and formaldehyde, were actually safe for humans after all.

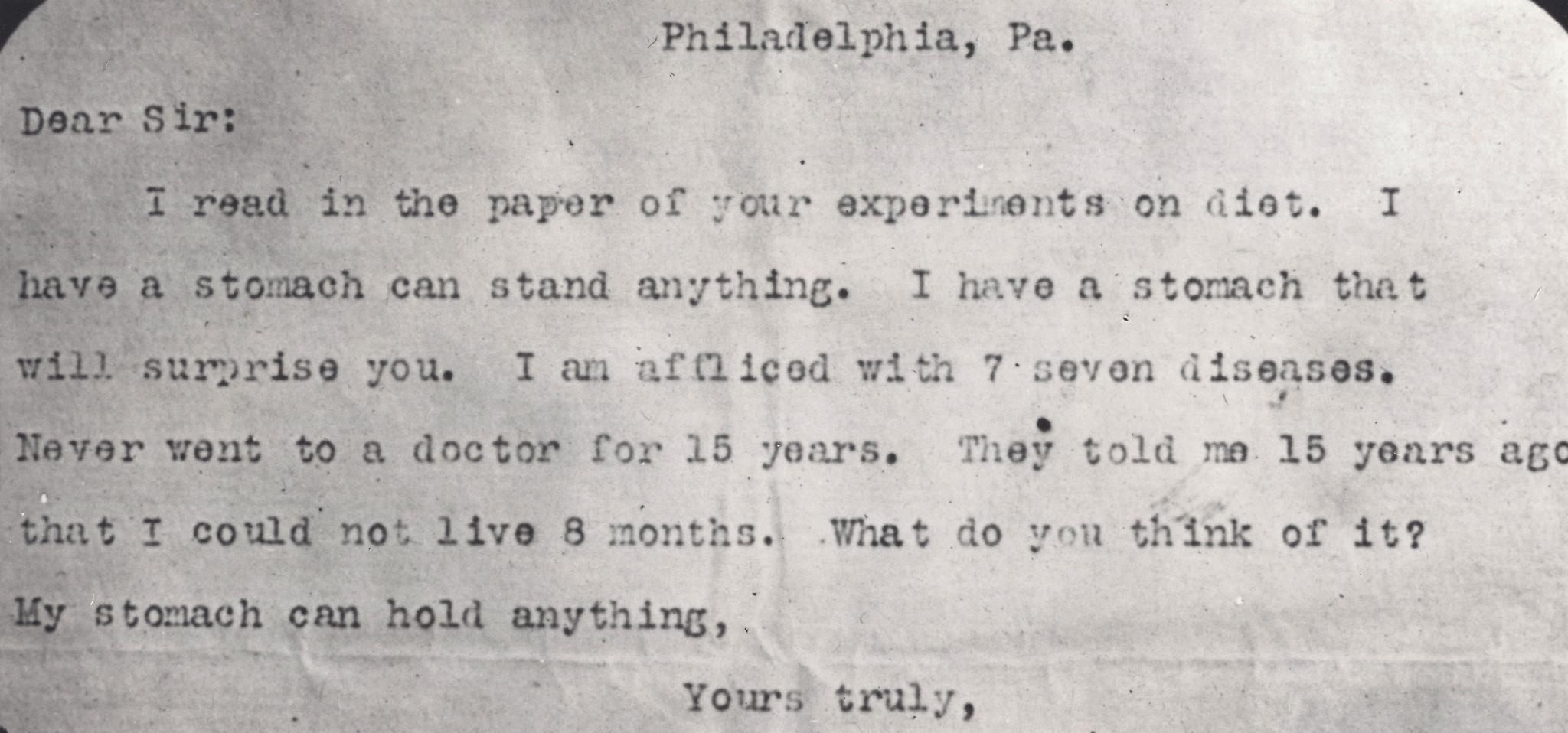

Members of the Poison Squad leapt at the chance to be part of this new research experiment; Dr. Wiley remarked at the time that his laboratory “became the most highly advertised boarding-house in the world.” Squad members were either employees of the Bureau of Chemistry or Georgetown Medical College students lured by the promise of extra money and free room and board.

Wiley did not try to obscure the fact that participants would be risking their health in service to his experiment. He even wrote a poem boasting about it:

Oh, maybe this bread contains alum and chalk,

Or sawdust chopped up very fine,

Or gypsum in powder about which they talk,

Terra alba just out of the mine.

And our faith in the butter is apt to be weak,

For we haven’t a good place to pin it

Annato’s so yellow and beef fat so sleek,

Oh, I wish I could know what is in it?”

Harvey W Wiley, with lab assistants. (Photo: FDA/Public Domain)

Using a $5,000 government grant, Wiley bought food, hired a cook, and brought on the first 12 members of the squad. Each participant was carefully observed: their weight, temperature, and pulse were recorded before the meal; stool and urine samples were tested; and cases of sickness and nausea were recorded. Women were not allowed to join.

As the Poison Squad ate meats and consumed drinks laced with increasing amounts of suspected poisons at their fine dining table, the public fell in love with their cause. Journalists breathlessly reported on their trials of these “young men of perfect physique and health.” Offensive yet popular minstrel shows added poison squad songs to their repertoire. Consumers across the country suddenly grew concerned about the safety of what they’d been eating.

While the Poison Squad wore formal clothing to their dangerous dinner parties, “No rosy-cheeked waitresses with snowy-white aprons serve the boarders,” wrote the Los Angeles Times in 1903. “Instead, a bespectacled scientist” served the “martyrs of science.” The article adds, ominously, that the Poison Squad “always leave the table a little hungry.” While the men benefited from free rent and a bit of prestige in the press, none of them were given individual credit for their work. To this day, most of their names are unknown.

In a statement, Wiley told the press that his experiments were “never carried to the extreme.” As the Poison Squad continued their work, however, the poisons they ate began to wear on them. By 1903 they’d been eating increasing amounts of borax, one of the most common preservatives at the time, with their meals for almost a year.

The slogan of the Poison Squad: None but the brave can eat the fare. (Photo: FDA/Public Domain)

Fed up, the Poison Squad went on strike that May. The Evening News wrote that “the twelve men at the borax table refused to take any more borax” in the summer months; apparently it was too much to go through the discomfort in the heat. Wiley compromised a bit; seven men agreed to eat the borax until late June, and the scientist consented to end the experiment early.

After the tumultuous borax experiment drew to a close, Wiley determined that, yes, borax caused severe stomach aches, loss of appetite and headaches, rendering his subjects “unfit for work of any kind.” Despite this, Wiley had no trouble getting new men to sign up for his next food additive experiment: salicylic acid. During those trials, however, Wiley was forced to abandon his tests to let the group recover.

By the end of the Poison Squad’s existence in 1907, those who didn’t withdraw from the experiments completely were observed to be “on a slow approach toward death” after eating long-term doses of the various additives. Formaldehyde, which was often used in dairy products, strained the kidneys and made the test subjects sick. Benzoate caused unhealthy weight loss and blood vessel damage.

When one squad member died of tuberculosis (allegedly after being weakened from poison), his family threatened to sue. Finally, after five years of testing dangerous ingredients, Wiley decided he had gathered enough evidence that these common food additives were hurting people.

A letter from a Poison Squad volunteer: “My stomach can hold anything.” (Photo: FDA/Public Domain)

Meanwhile, The General Federation of Women’s Clubs and the National Association of Colored Women had long advocated for issues that affected women and their homes, including preserved food. Women’s groups hit the streets with food safety pamphlets and classes in multiple languages, intended to warn women of the dangers that lurked in common products.

As the public’s outrage against unregulated additives began a slow boil, Alice Lakey from the General Federation of Women’s Clubs began a letter-writing campaign in support of the Pure Food and Drug Act, which would stop companies from adding untested chemicals and fillers like sawdust to the meals of families. As Wiley gained prominence for his Poison Squad’s success, he joined forces with the women’s food safety cause, which was proving highly influential (despite believing that women were “not intended by nature…to follow in the pursuits of men”).

In 1905 Lakey became the head of the Pure Food Committee. She and Wiley brought the letters of support to President Roosevelt, and later, at a Congressional hearing regarding the Pure Food and Drug Act, these letters played a key role. Wiley later credited Lakey and other women with the act’s success, saying “the passage of the bill was due to the women’s clubs of the country.”

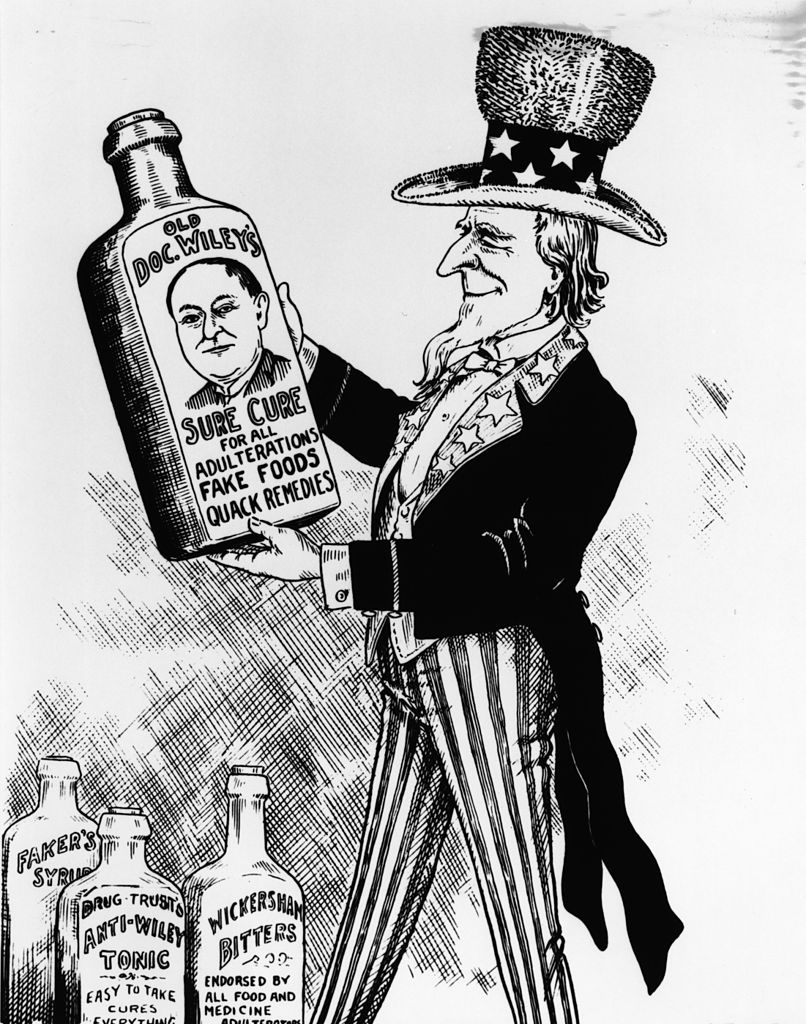

The Pure Food and Drug act was passed in 1906, setting a precedent to the later Food, Drugs and Cosmetics Act and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The law prevented “the manufacture, sale, or transportation of adulterated or misbranded or poisonous or deleterious foods, drugs or medicines, and liquors.” Any food or drug product sold in the United States now had to include all its ingredients, including a percentage of narcotics if relevant, on the label for the consumer.

A cartoon paying tribute to Harvey Wiley’s reforms. (Photo: FDA/Public Domain)

Wiley’s work even inspired a fad for local and industry-specific “poison squads.” A year after his experiments ended, a new week-long Poison Squad to test preservatives formed in New York City. Dried fruit packers made their own Poison Squad to re-test sulfites in their products, which Wiley had criticized. A Coffee Poison Squad later recorded the effects of caffeine. In 1913 The Pittsburg Press wrote that the Poison Squad of the city department of health was visiting local ice cream shops, assuring everyone that ice creams and sodas appeared to be safe.

While Wiley’s earlier career had hinged on poisoning his own vigorous employees, in later years he became even more focused on the crusade against the consumption of untested preservatives and drugs. Between 1912 and 1930, Wiley headed the laboratories at the Good Housekeeping Institute, which tested household and food products, which is still done to this day.

Every time we peek at the mile-long list of ingredients in a packaged muffin, and note that chalk is not one of them, we owe our thanks to the young men who bravely swallowed poisonous additives on behalf of American consumers.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook