For Sale: A Penny That Stopped a Bullet and Saved a Life

It’s not the only everyday object to have done so on the battlefield.

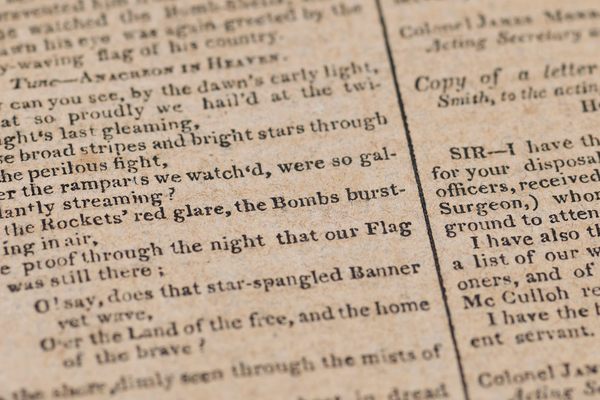

Of the three Trickett brothers who left their home in Lincolnshire, in eastern England, to fight for the United Kingdom in the First World War, only John would survive. Horace and Billy were among the more than eight million soldiers killed in the Great War, which saw casualties on an unprecedented scale due to the advent of new, more advanced weapons. John, however, was saved by the most ordinary and rudimentary equipment on the entire battlefield: a penny in his breast pocket that deflected a bullet intended for his heart.

The penny, issued in 1889 (10 years before John was born) and severely bent from the bullet’s impact, will be sold on March 22, 2019, in Hansons Auctioneers’ Medals and Militaria Auction. At press time, the highest bid was £1,700 (more than 2,200 dollars), vastly exceeding Hansons’s initial estimate of between £100 and £200 (or, 130 to 260 dollars). The lot includes a British victory medal as well as Trickett’s 1918 discharge certificate, among other items.

While we don’t know precisely when and where Private Trickett had his brush with death, Adrian Stevenson, Hansons’s militaria expert, says that the incident occurred in 1917, on the war’s Western Front. The bullet, fired by a German soldier, ricocheted off Trickett’s penny and traveled up through Trickett’s nose, exiting through his left ear. Trickett lost hearing in that ear for the rest of his life, his granddaughter Maureen Coulson told Hansons. Trickett received an honorable discharge from the military in September 1918. After coming home, he got married, had eight children, and worked as a postmaster and switchboard operator.

Coulson answered a Hansons advertisement for a routine valuation event, bringing the penny and Trickett’s other effects to Stevenson. Ironically, the coin was “one of those real impossible things to value,” says Stevenson, who eventually settled on a relatively low estimate for the item due to the “very modest” value of the metal itself. It’s not the first time in Stevenson’s career that he’s heard of an everyday item blocking a bullet and making the difference between life and death. Bibles, shaving mirrors, and cigarette cases, he says, have all done the same—and during the war, some manufacturers even began advertising thicker mirrors, explicitly pitching their life-saving potential.

“It’s strange to think,” said Coulson, “that, but for that penny, [Trickett’s] children would not have been born and I wouldn’t be here.” There could be many more families throughout the world who could say the same about other objects: Since Coulson delivered the coin to Hansons, the auction house has also acquired a shrapnel-damaged flask and belt buckle that may have saved their carriers.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook