For Sale: A POW Journal Documenting World War II’s ‘Great Escape’

A look inside the mind of a legendary plot.

The 75th anniversary of World War II’s most iconic prisoner-of-war escape is less than two weeks away, on March 24, 2019. Just in time, Hansons Auctioneers in England is offering a rare relic of the daring feat: a diary that takes us inside the mind of one of the prisoners who planned it.

In its “Medals & Militaria” auction on March 22, 2019, Hansons will sell the journal that belonged to the late Royal Air Force Flight Lieutenant Vivian Phillips while he was held in the Nazis’ Stalag Luft III camp, in present-day Poland. According to the auction house, it is the only such diary believed to have survived not only the camp, “but also a forced march of hundreds of miles across Germany” later in the war. It is expected to sell, alongside Phillips’s medals, for around $20,000 (or, £15,000 to £18,000).

Phillips was captured by the Nazis in May 1943, when his plane was shot down over Amsterdam during a bombing raid on a power station. He joined prisoners from a variety of countries including the United States, Canada, Australia, France, Norway, Latvia, and Belgium in Stalag Luft III, which the Nazis considered one of their more secure POW camps. That’s why Roger Bushell—a Royal Air Force pilot who had been shot down during the rescue at Dunkirk, and who had subsequently escaped from two German POW camps—was being held there when Phillips arrived. Undeterred, Bushell was planning another escape, despite the microphones that the Nazis had placed nine feet beneath the ground, and the sandy terrain that did not lend itself to tunnel construction.

As History details, the prisoners dug their tunnels—codenamed Tom, Dick, and Harry—via a trapdoor underneath a stove, which was kept lit in order to deter guards from approaching it. Slowly, they were able to dig beneath the range of the microphones, taking off their clothing so the guards wouldn’t notice any telltale sandy stains.

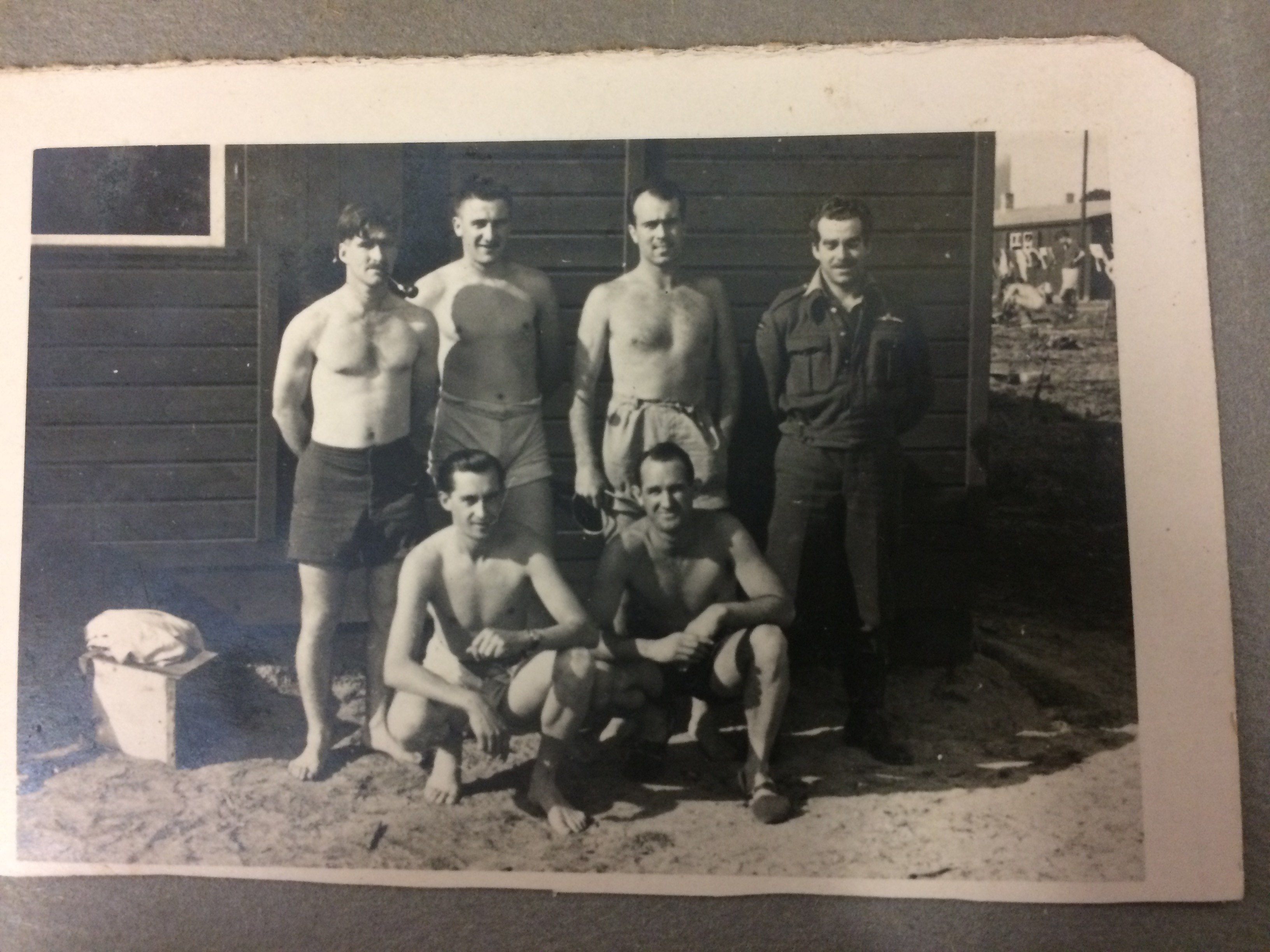

“All this was done under the very noses of the guards,” wrote Phillips in his journal, one of those distributed to POWs by the Canadian Red Cross. He himself was one of the diggers, which Hansons says would have suited him as he was “rather short of stature and from Welsh coal-mining stock.” Phillips wrote that, eventually, he “graduated to a kind of foreman” in “charge of a gang of eight fellows…” A model of classic British stoicism, Phillips nonchalantly noted that “the whole thing was most efficiently run…” The operation inspired the 1963 Hollywood classic, The Great Escape.

When the time came for the prisoners to put their tunnels to use, they had to draw names at random so as not to overwhelm the makeshift passageways. Phillips’s name was not drawn, but he was actually lucky: Only three of the 76 escapees ultimately eluded the Nazis. The rest were caught within two weeks, and 50 of the prisoners—including Bushell—were then (illegally) executed on Hitler’s personal orders. (A postwar military tribunal found 18 Nazis guilty of war crimes for the executions; 13 of them were executed in turn.)

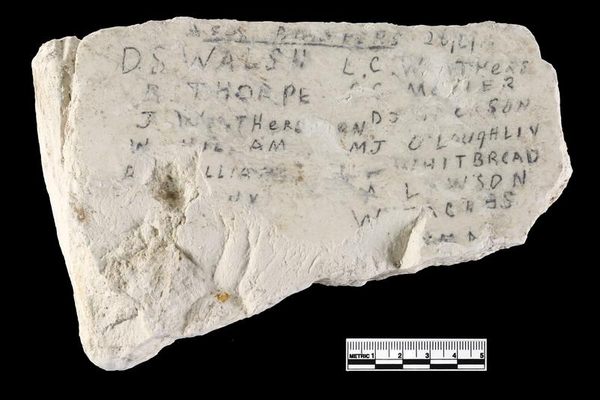

And so, even with all of the writings and drawings depicting daily life in the POW camp, and describing plans for the escape plot, the most striking section of Phillips’s journal may be the “In Memoriam” list, which names the executed captured prisoners and their countries of origin. It cements the journal as more than a record of brilliant enterprise in the face of fierce adversity, but as a testament to enduring humanity in times of brutality.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook