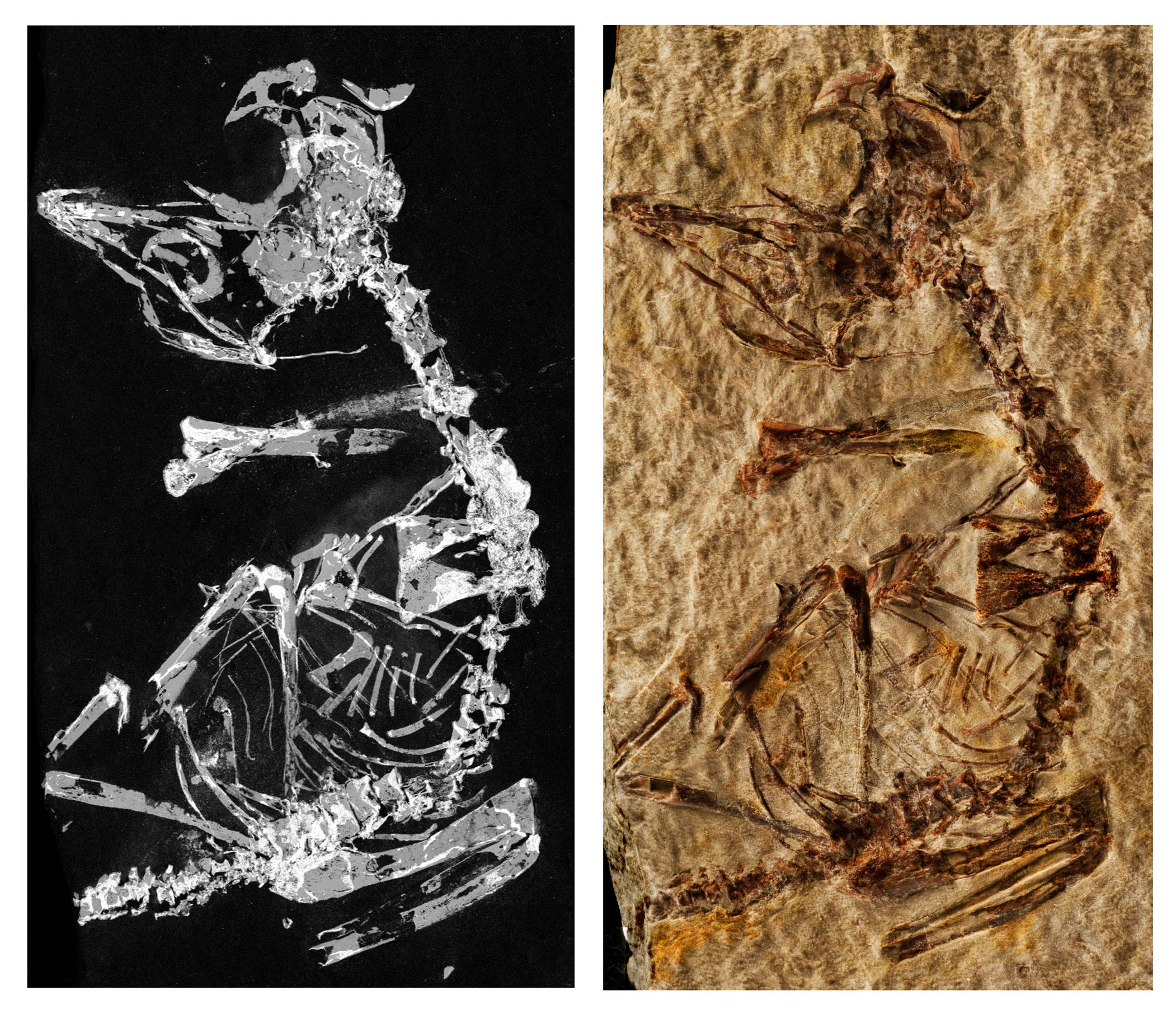

Found: A 127-Million-Year-Old Fossil of a Fledgling

These tiny, prehistoric bones tell a story about flight.

One day around 127 million years ago, a hatchling emerged from its shell. This petite member of the enantiornithine family—measuring about the length of your pinky finger, and weighing less than three ounces—didn’t have much time to get to know its dinosaur neighbors or the terrain of its prehistoric world. It died soon after cracking through.

The bird’s loss is researchers’ gain, because its bones tell a story. The hatchling’s skeleton—which is well preserved and nearly complete—offers researchers a window into the stages of avian development in the Mesozoic era.

When the wee enantiornithine was unearthed at the Las Hoyas site in Spain, the skeleton wasn’t immediately scrutinized—but not for lack of curiosity. The techniques needed to study the tiny bones “had not yet been developed when the specimen was discovered,” Fabien Knoll, a researcher at the University of Manchester and project lead, explained to BBC. Now, though, tools such as synchrotron microtomography and elemental mapping have allowed researchers to take a closer look, which Knoll and company describe in a new paper in Nature Communications.

By studying bones, researchers can glean a lot of information about how a creature spent its life. Analyzing a skeleton reveals “a whole host of evolutionary traits,” Knoll said in a statement.

Take flight, for instance. A bird’s bones must be fairly ossified in order to support the weight of flapping and hurtling through the air. The relative dearth of fossilized avian embryos and hatchlings means that researchers have a paucity of information about when in their development prehistoric birds might have lifted up into the sky. In this case, the sternum was still more cartilage than bone, leading the researchers to conclude that the hatchling probably couldn’t fly.

There’s still plenty more to learn about this long-deceased specimen, as well as its relationship to the living creatures speckling the sky, said Luis Chiappe, a co-author and director of the Dinosaur Institute at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, in a statement. “It is amazing to realize how many of the features we see among living birds had already been developed more than 100 million years ago.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook