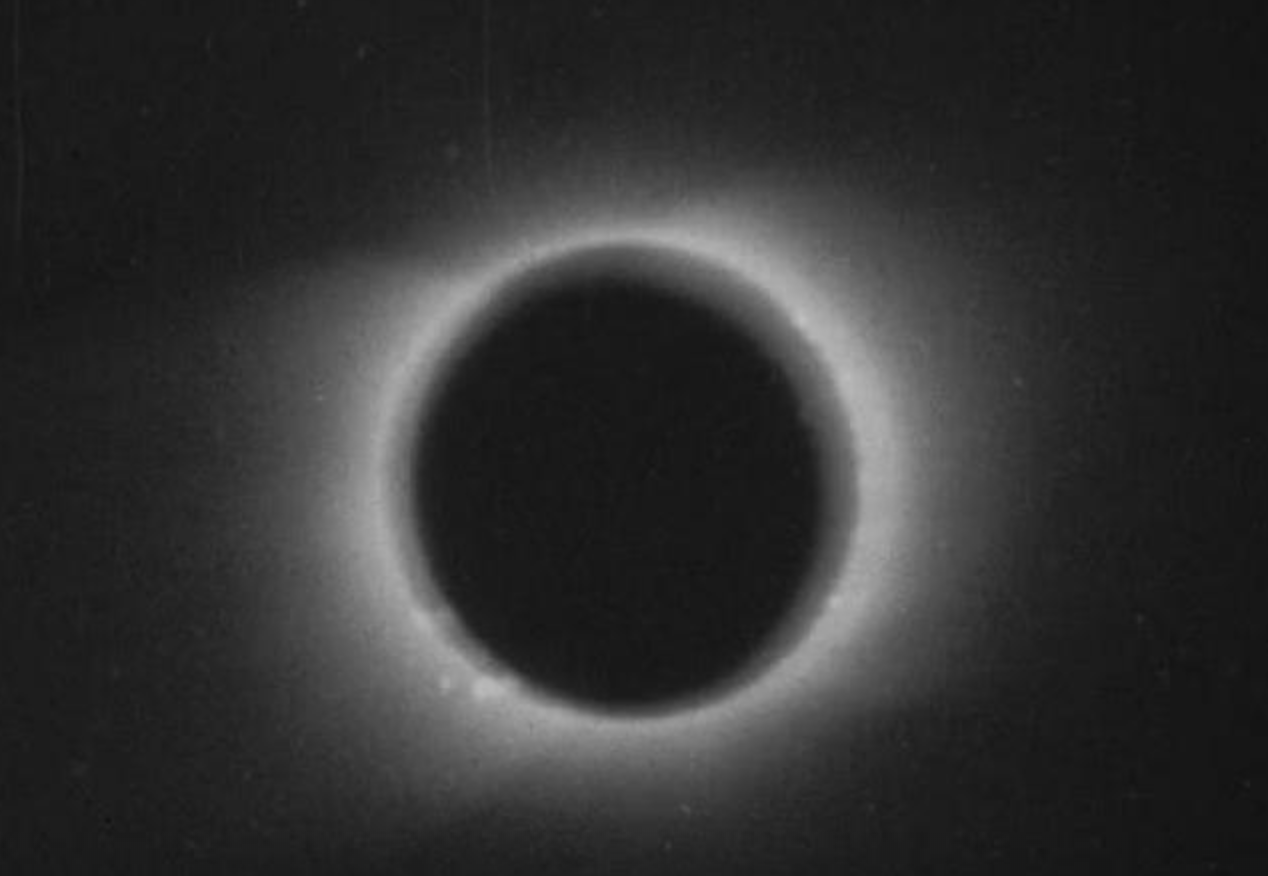

The Earliest Film of an Eclipse, Recently Rediscovered, Is Pure Magic

Nevil Maskelyne, Jr., made history in 1900 with footage that still astonishes experts.

In 1900 in North Carolina, a British magician captured the first-ever footage of a solar eclipse. The film, which lasts one minute and eight seconds, soon disappeared. Historians hunted for decades to track down this rare scientific marvel, to no avail. But on May 30, 2019, archivists from the British Film Institute and The Royal Astronomical Society announced the rediscovery of this monumental clip of the moon blotting out the sun. It is thought to be the oldest surviving astronomical film, according to a press release.

Although the film disappeared for over a century, archivists knew it existed thanks to an advertisement for its premiere placed in The Era, a Victorian trade paper that chronicled the events of British theaters, Bryony Dixon, the BFI’s silent film curator, wrote in an email. At least 80 percent of all films made in the early 1900s are now lost to time, Dixon says, so it was no surprise that the eclipse footage might have disappeared. “This was one of my most-wanted missing films from the early period,” she says. In 2018, when Sian Prosser, a curator at the RAS, called Dixon to ask for help identifying short footage of an eclipse, Dixon knew exactly what film had just been found.

The film is even more fascinating considering the occupation of its cinematographer, the famed British magician-turned-filmmaker Nevil Maskelyne, Jr. (To be clear, the astronomically inclined 19th-century magician Nevil Maskelyne, Jr. is not the same person as the 18th-century astronomer Nevil Maskelyne; oh, to live in a time when the name Nevil Maskelyne was the equivalent of John Smith!)

Magic ran in Maskelyne’s family blood, as his father, John Nevil Maskelyne Sr., ran Egyptian Hall, London’s oldest magic theater. To capture the footage, Maskelyne Jr. traveled to North Carolina in 1900 with his father’s telescopic camera equipment in tow, Dixon says. The film represents Maskelyne’s second attempt at documenting a solar eclipse. Just two years earlier, he traveled to Buxar, India, to film an eclipse, the footage of which was promptly stolen on his journey home. No information about Maskelyne’s equipment survives today, which Dixon chalks up to a healthy secrecy that would have accompanied a pending patent application.

But with whatever equipment he had, Maskelyne managed to capture the enormously challenging exposure changes that accompany an eclipse in progress. At totality, the diamond ring effect surrounding the corona of an eclipse affects an image’s exposure, Dixon told Live Science. Somehow Maskelyne changed the exposure of his camera’s aperture to capture how the corona looked as it faded back into the sun.

The footage was captured on 120-year-old celluloid, which had to be scanned and reassembled, frame by frame, to 35-millimeter film by conservation experts at BFI. This painstaking conservation process befits the careful creation of the film. “It’s complex to photograph an eclipse—so many things can go wrong,” Dixon says. “It’s the fearless ambition that impresses me most about the film, as well as the simple beauty of the image.”

You can watch Maskelyne’s historic short online, and capture footage of your own as the next solar eclipse rolls around on April 8.

This piece was originally published in 2019 and has been updated as part of Atlas Obscura’s Countdown to the Eclipse, a collection of new stories and curated classics that celebrate the 2024 total solar eclipse and the Ecliptic Festival in Hot Springs, Arkansas.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook