Found: A Grasshopper Embedded in a Van Gogh

One of the perils of painting outdoors.

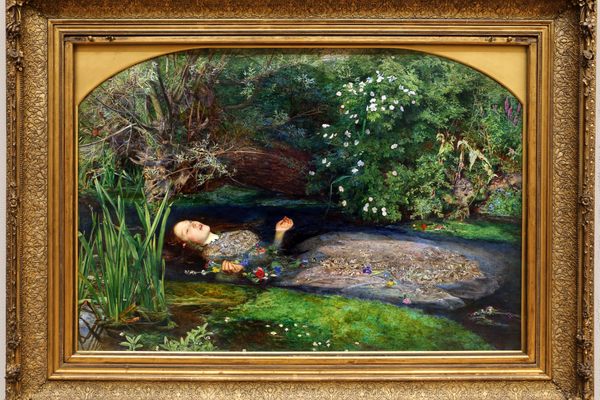

Insects have long had a place in the art world, from ancient Egyptian scarabs and Salvador Dalí’s swarming ants, to the Asian craft of beetlewing embroidery and Damien Hurst’s In and Out of Love (White Paintings and Live Butterflies).

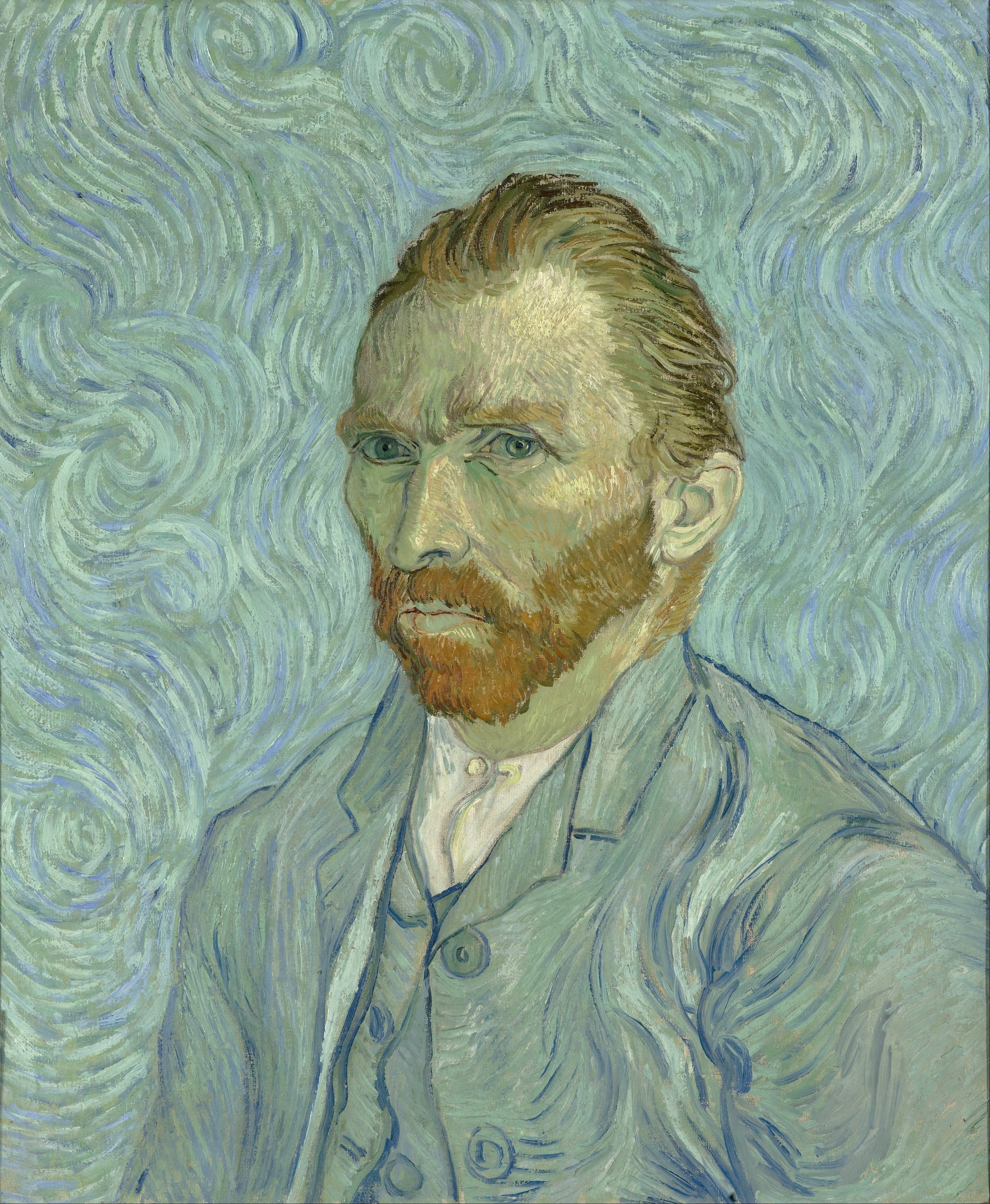

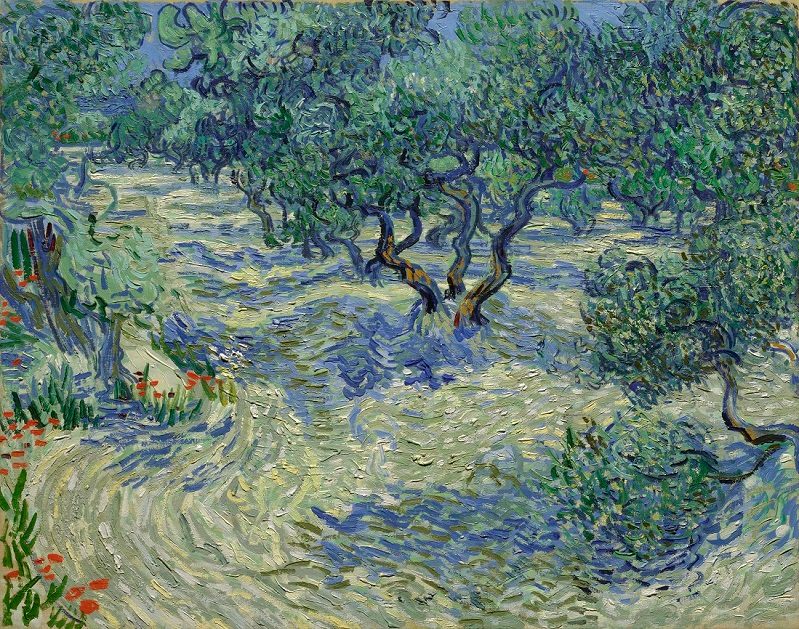

Recently, a team of curators and conservators from the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City was examining Vincent van Gogh’s Olive Trees, one of 18 works on the theme by the Dutch Post-Impressionist. Most of these works were created when he was being treated at a psychiatric facility in the French town of Saint-Rémy-de-Provence (birthplace of Nostradamus, too) in 1889 and 1890. Under magnification, the museum team spotted an unexpected visitor in the painting’s impasto—pieces of a small grasshopper.

“We think that the dead grasshopper was probably blown into the painting by the wind and got caught in the thick paint,” says Kathleen Leighton, a media relations manager at the museum. “Van Gogh used to paint very quickly with very thick paint, so he probably did not realize it was there. But we are not totally sure about that.”

Van Gogh, like many artists, worked outside in the elements, and used to complain about the wind and flying insects in famous letters to his beloved brother Theo. “But just go and sit outdoors, painting on the spot itself! Then all sorts of things like the following happen—I must have picked up a good hundred flies and more off the 4 canvases that you’ll be getting, not to mention dust and sand … when one carries them across the heath and through hedgerows for a few hours, the odd branch or two scrapes across them … ” he wrote in an 1885 letter cited in a museum press release.

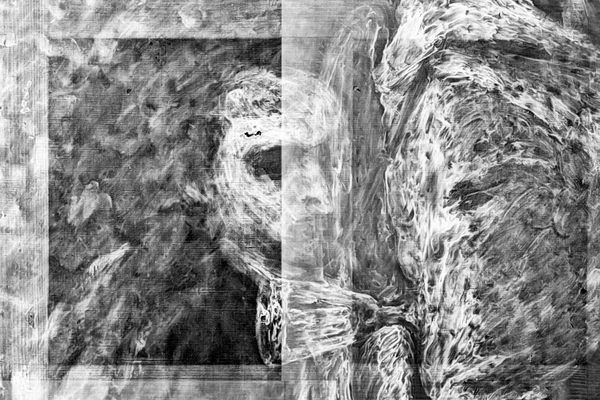

Painting conservator Mary Schafer spotted the insect parts in the lower foreground of the landscape, but explained that due to their size and the way they are embedded, museumgoers won’t be able to see them. It’s not unusual to find insects or plants in paintings that were completed outdoors, she said, but that researcher take a special interest in them, since natural elements can help identify the season in which a work was painted.

That did not work in this case, though, as an examination by paleoentomologist Michael S. Engel, of the University of Kansas and the American Museum of Natural History in New York, suggested that the insect, which is missing its thorax and abdomen, was already dead before it landed on the canvas, so it could have ended up there at any time of year.

The discovery is part of ongoing efforts to combine scientific study of the artist’s paintings with historical research to better understand his work process. In the release, museum executives Julián Zugazagoitia and Mary Louise Blackwell said, “Olive Trees is a beloved painting at the Nelson-Atkins, and this scientific study only adds to our understanding of its richness.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook