Found: A Runic Inscription on a Viking Whetstone

Experts in Norway are asking the public to help tell if it is a name or something more sinister.

Runic alphabets, a system of phonetic symbols used by Germanic peoples from about the first century through the medieval period, have been deciphered but remain a mystery for linguists. We know that they developed out of one of the Old Italic languages, such as Raetic, Venetic, Etruscan, or Old Latin, all of which share the same angular letters typical of runes. But many of the Old Italic alphabets were used in Italy, and it’s unknown how they were transmitted to Denmark and northern Germany, where the first runic-inscribed objects were found.

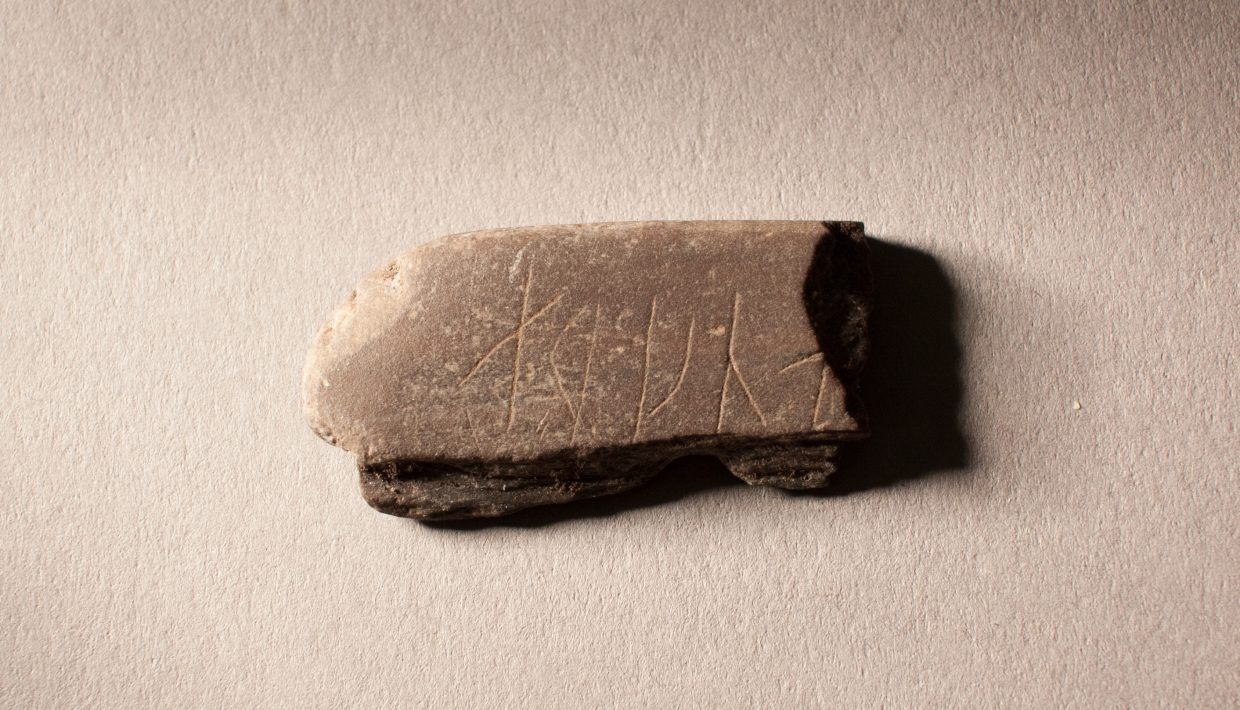

In October, archaeologists from the Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research (NIKU) were conducting excavations ahead of a railway project in Oslo, Norway, and found a small piece of polished slate dating to around 1,000 years ago, when the Vikings inhabited Norway.

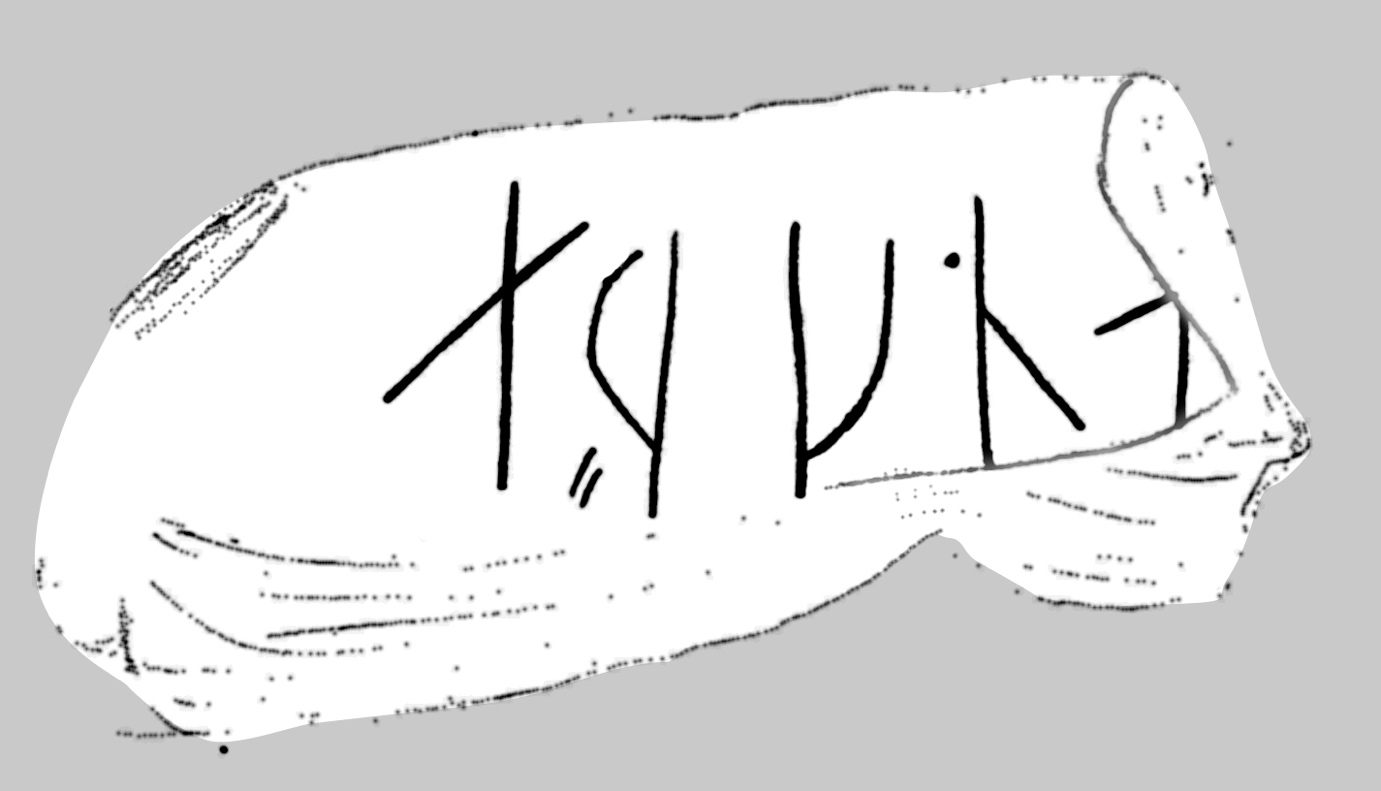

The medieval stone, which was identified as a whetstone (for sharpening knives), held a cryptic runic inscription. “On the whetstone, the runes ‘æ, r, k, n, a’ appear. But it is not easy to tell what they mean,” Kristine Ødeby, field supervisor on the excavations, said in a release. According to NIKU’s rune experts, the characters were an attempt to spell someone’s name, or could be interpreted as dark words such as “scared,” “ugly,” or “pain.”

Runes have long been associated with magic and fantasy. The word comes from a Germanic root meaning “secret” or “whisper,” and it is believed runic inscriptions were engraved in stones or swords throughout Scandinavia for luck or as spells. They play a similar role in J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit (1937), where they appear on a map as a connection to the mountain-dwelling dwarves.

But in this case, the mystery of these runes might be more quotidian than supernatural. Experts believe that the whetstone is so unclear because the writer was a beginner. “This is probably an unsuccessful attempt to write a name or another rather trivial inscription, but we can see that this is hardly a trained rune carver,” said Karen Holmqvist, a specialist in runes at NIKU.

The tiny whetstone is the second runic artifact of this kind ever found in Norway, and has spurred a debate among experts on how people in medieval Oslo used written language. According to Ødeby and Holmqvist, the most likely scenario is that runic writing was widespread but that most people were not fully trained writers. The experts are open to alternative interpretations and started a blog (in Norwegian) where anyone can give their two øre. As Ødeby explained, “With so many possible interpretations, this is an exciting find for scholars, amateurs, and storytellers alike.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook