Dalton, GA: How a Bedspread Fiefdom Became A Carpet Kingdom

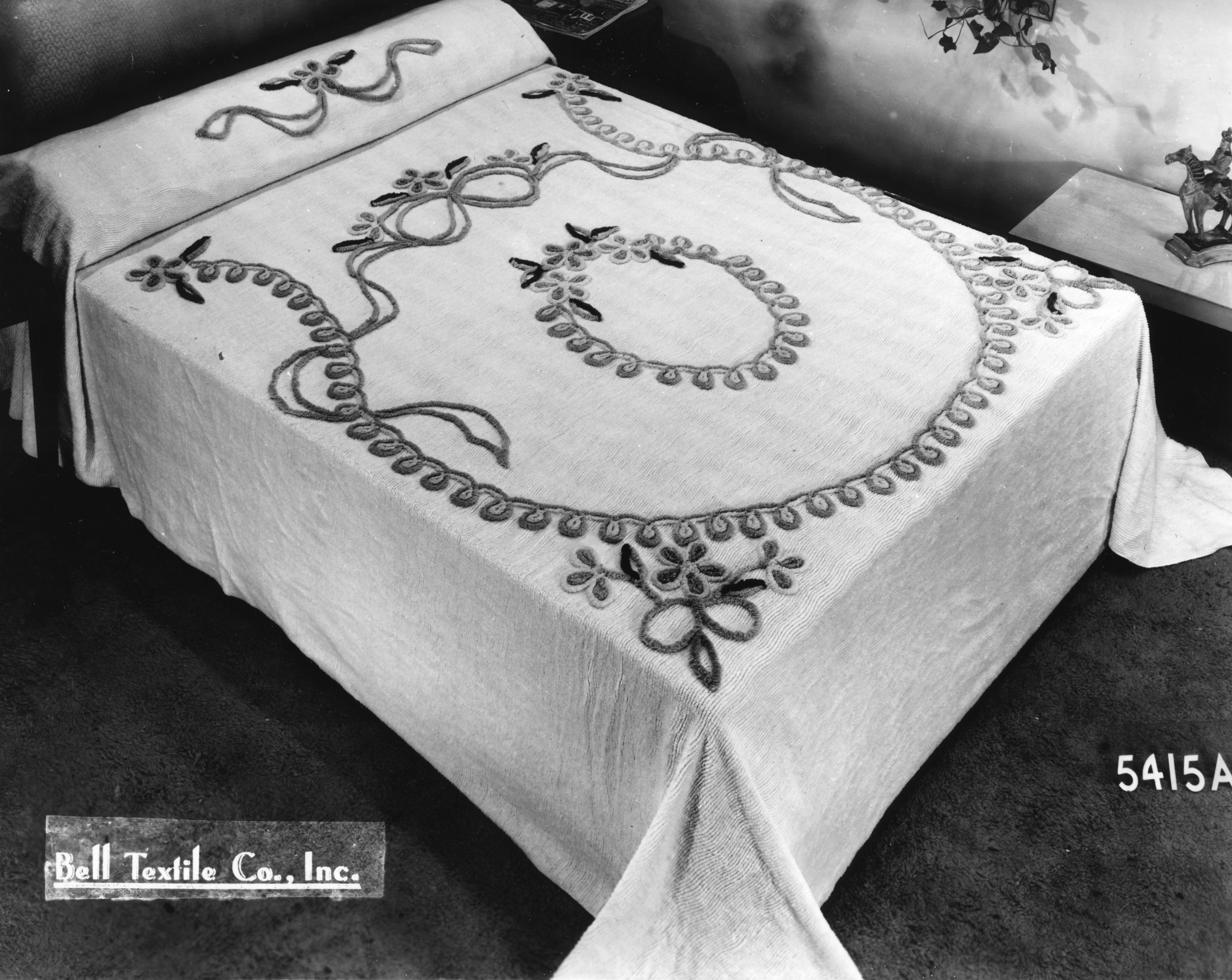

Needlepunch embroidery, 1946. (Photo: Courtesy The Bandy Heritage Center for Northwest Georgia)

Needlepunch embroidery, 1946. (Photo: Courtesy The Bandy Heritage Center for Northwest Georgia)

This is the first installment of the Other Capitals of the World, a series where we’ll look beyond the typical seats of power to examine less typical centers of industry. Have a suggestion? Let us know.

If you’re standing on a carpet in a hotel or at an airport or even in a friend’s living room, then there’s a very good chance you’re standing on a carpet manufactured in, or around, Dalton, Georgia.

More than 85 percent of the carpets sold in the United States, and around 45 percent of the residential and commercial carpets found worldwide, are made within a 65-mile radius of this small city of 32,000 souls nestled in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains.

In Dalton you can find the headquarters of such global carpeting behemoths as Beaulieu, Daltonian, J & J Industries. Shaw and Tandus, companies that create some 12.2 billion square feet of floor covering each year, enough to cover the entirety of Hong Kong in a thick, rich shag. So many carpet mills cluster together in Dalton that it has been known to snow blue due to the number of dye particles in the air.

Why this carpet convergence? The answer, as any Daltonian worth his weft will tell you, is due to the stitching genius of Catherine Evans Whitener, commonly referred to as Dalton’s “First Lady of Carpet.”

Catherine Evans Whitener, 1946. (Photo: Courtesy Crown Garden & Archives/ The Bandy Heritage Center for Northwest Georgia)

Whitener was 15 years old when she crafted a bedspread for her brother’s wedding in 1895. She had been inspired to do so by seeing a colonial coverlet at a relation’s house which had been made using the long-forgotten technique of candlewick tufting—using raised tufts of a soft cotton thread commonly used to form candle wicks. The teenage Whitener did not know how to tuft, but through painstaking experimentation she recreated the technique. Her hard work paid off. The bedspread she gave to her brother became a local, and then a national, sensation.

”Chenille”, the French word for “caterpillar”, described the appearance of the rows of tufts that made the bedspread’s pattern, c. 1960s. (Photo: Courtesy The Bandy Heritage Center for Northwest Georgia)

Within days of the wedding Whitener was swamped with more orders than she could possibly fill, so she began to teach her neighbors the technique. A cottage industry was born practically overnight. At the time Dalton was a sleepy cotton mill town and the area around it largely agricultural with an impoverished white population. Tufting bedspreads offered much-needed income to these families. By 1920 over 10,000 “tufters” were working out of their own homes in the Dalton area, racing to fulfill the country’s seemingly insatiable need for bedspreads.

Worker Emma Puryear admires a rose print bedspread, 1946. (Photo: Courtesy The Bandy Heritage Center for Northwest Georgia)

With the advent of the motorcar, tourists driving down to Florida were drawn here, and by the 1930s bedspreads stretched for miles along the side of Dalton’s Highway 41 so that it became known as “Bedspread Alley” or “Peacock Alley”, after one of the most popular designs. By the end of the decade the sheer demand had caused bedspread manufacturing to leave the tufters’ homes and move into factories.

Chenille on the “spreadline”, 1946. (Photo: Courtesy The Bandy Heritage Center for Northwest Georgia)

With the factories came fortunes. The first bedspread millionaire was Mr. B.J. Bandy of Dalton, Georgia, naturally. As such, before it became the Carpet Capital of the World, Dalton was known as the Bedspread Capital of the World.

A model in a chenille robe, c. 1960s. (Photo: Courtesy The Bandy Heritage Center for Northwest Georgia)

It is not known why people suddenly felt the need to start covering their beds with tufted cotton blankets in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Was it due to propriety, prosperity, or some deeply buried Freudian passion? Whatever the reason the urge disappeared almost as quickly as it had arrived. As the craze faded in the 1950s, the now centralized and mechanized bedspread industry began to branch out, creating bathrobes, small rugs and tank sets (those peculiarly persistent woolly covers for toilets). But it was with the introduction of the broadloom, which allowed room-sized carpets to be created, that Dalton found its future. Why just cover a bed when you could cover an entire home? American floors were lost for decades beneath thick wall-to-wall carpeting.

Carpet tufting machine with creel rack holding yarn cones, c. 1960s. (Photo: Courtesy The Bandy Heritage Center for Northwest Georgia)

Historically, of course, carpet manufacturing has been located nowhere near the state of Georgia—it’s long been the preserve of Middle Eastern states, most notably Persia. Indeed the American South would seem a particularly unfriendly environment in which for carpeting to flourish considering it was the South that coined the pejorative term “carpetbagger” to describe the opportunistic Northern businessmen operating there after the Civil War

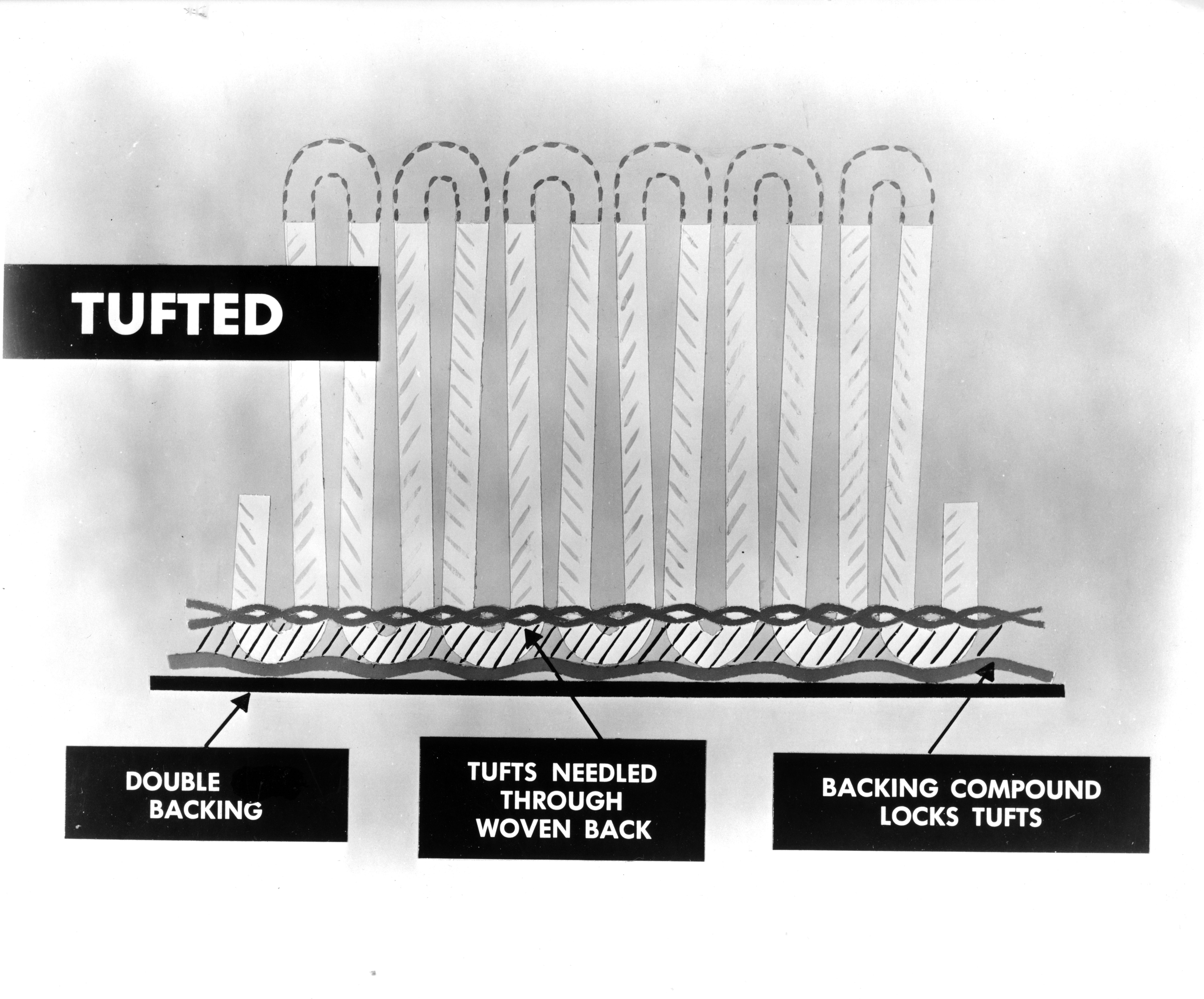

But the dyeing and finishing companies that had appeared to serve the old bedspread industry were perfectly placed to help Dalton’s new carpet manufacturers, and the introduction of petrochemical-derived synthetic fibers such as nylon and polyester made carpets both affordable and durable. Meanwhile generations of art school graduates found regular employment designing the carpets’ endlessly repeating patterns. Yet despite these changes, the technique at the core of the business remained that first practiced by Catherine Evans Whitener—the vast majority of carpet manufactured today is still tufted (as opposed to being woven or needlepunched).

Tufting diagram, c. 1950s. (Photo: Courtesy The Bandy Heritage Center for Northwest Georgia)

By the 1970s, Dalton was thriving and had more millionaires per capita than any other city in the United States. Recently, however, the city has been facing some headwinds that even the Dalton-based lobbying group, the Carpet & Rug Institute (tagline “Carpet Makes the World Better”) has not been able to dispel. In the wake of the financial crash of 2008 and the subsequent housing market decline, many of the old carpeting businesses were forced to consolidate. Added to this was the relatively recent rise of solid flooring, headed by such engineered floor manufacturers as the Swedish firm Pergo, which has been making rapid incursions into homes worldwide. In the last decade carpets have been accused of causing asthma and of being generally unhygienic.

Carpet no longer feels quite as comfortable beneath our feet.

Yet the Carpet Capital of the World is still expanding its reach, albeit in unconventional ways. One of the synthetic chemicals found in many of Dalton’s carpets is perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) which is used to engender stain resistance in carpets. Unfortunately, the same characteristics that PFOA shares with carpets allows it to spread easily and endure in the environment without breaking down. It has been found in extremely high levels in Dalton’s Conasauga River, and researchers have found the chemical—which is also used in the creation of non-stick cook wear—as far afield as the Arctic. Somewhat worryingly PFOA is present in nearly every American’s bloodstream. Soon, it seems, the whole world will be carpeted in it, and then Dalton will have dominion over us all.

Sewing fringe on a throw rug, c. 1950s. (Photo: Courtesy The Bandy Heritage Center for Northwest Georgia)

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook