Why the World’s Greatest Toasts Happen in Georgia

Saying “Cheers!” is for amateurs.

The first toast is to time.

Djumbo starts by addressing humanity’s place in the world. As a toastmaster, he represents a Georgian tradition that makes drinking and feasting into an almost sacred act. With a raised glass, he reminds the table of humanity’s destructive nature and how we are slowly consuming the planet. He then reminds us that God placed this struggle before us and that He also gave us time so that we could learn. He ends by looking each of us straight in the eye. “I would like to drink to bless the day, the month, the year, the minute we were each born,” he says. “Let’s drink to the time God created human beings.”

We raise our glasses and drink. There are four of us—two guests and Djumbo and his wife. We are sitting inside a small house on a mountain ridge in Western Georgia. The house has been in Djumbo’s family for four generations, and its wooden walls have been burnished black by smoke and time. We are eating around a small, low table, next to a wood stove where Djumbo’s wife Irena occasionally gets up to stir a new dish. The dishes are endless.

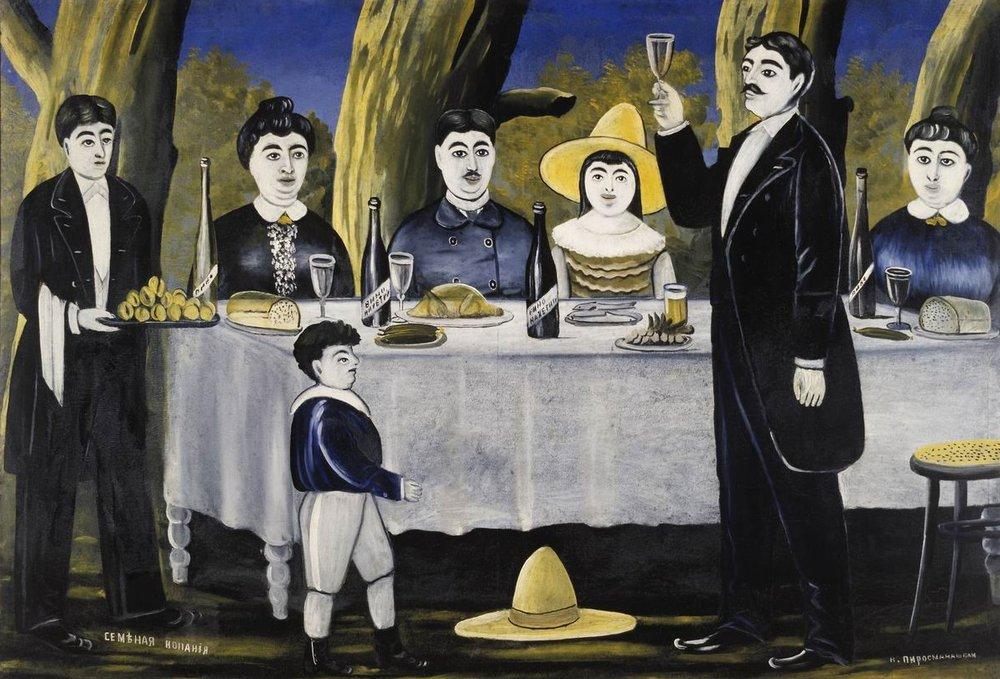

This type of meal is called a supra, and it most closely translates to a feast. Supras can happen in occasions as informal as a group of friends meeting for dinner or as serious as a wedding or a funeral. Guiding and watching over each supra is a man like Djumbo—a tamada or toastmaster.

The table overflows with food. We eat for eat for five hours, but the dishes keep coming: mushrooms, potatoes, fish, cheese, breads, and skewers of barbecued pork with the fat still dripping. (Djumbo roasted the skewers over a small bonfire after seasoning them in a savory and addictive layered sauce.) Djumbo drives tourist buses for a living, and he invited us to his home after a day spent in the mountains gossiping in Russian. Hospitality is deeply embedded in Georgia, and as we are guests, a supra was necessary.

Every fifteen minutes, Djumbo instructs us to raise our glasses. We are drinking chacha, a traditional Georgian moonshine that can be as strong as 80 percent proof. Djumbo brewed the chacha himself, so its alcohol content is anyone’s guess. Every drink of chacha is accompanied by a toast, and every toast is like a poem that lasts as long as fifteen minutes and address the biggest themes in life.

Djumbo’s speaks beautifully. He speaks of death, lost loved ones, peace, religion, and the insecurity of the future. He uses nature metaphors and discusses the connection between Dostoevsky novels and the Bible. He laments the corruption of power and talks about Stalin and whether revolution is possible without bloodshed.

“Even though you’re young, you have definitely lost people in your lives,” he says in a toast. “Young people also die. It’s too fast. Life is but a passing dream.” We clink our glasses. “Never forget them. It’s a sin to forget them.” It is impossible to sit at Djumbo’s table and remain unmoved.

Djumbo is famous in his region. Irina, his wife, says that sometimes hundreds of people gather to see him give toasts. Families ask him to be the tamada at weddings and funerals, and he spends weeks talking to the friends and family to personalize and prepare his toasts.

John Wurdeman, an artist, restaurant owner, and toastmaster who has lived in Georgia for 21 years, says he has heard of toastmasters getting paid for officiating a ceremony, but that it is rare. Many of them would be offended by payment. “[Being a] tamada means everyone respects you and considers your words and ideas important; often they are men of influence and stature,” he says. “So they would think it’s below them if money was offered.”

Djumbo was once a professor of Russian literature and has an encyclopedic knowledge of the classics. But his journey to becoming a toastmaster was largely informal. There are no toastmaster schools. While some institutions once offered training, the eldest and most well-spoken man at a feast usually takes on the role. (Women acting as toastmasters is rare but a recent development.) In cases such as Djumbo’s, their reputation spreads by word of mouth until they become famous in their community. They occupy a unique role: Good tamadas are both a master of ceremonies and something close to a priest. Sometimes they make jokes; sometimes they provide catharsis.

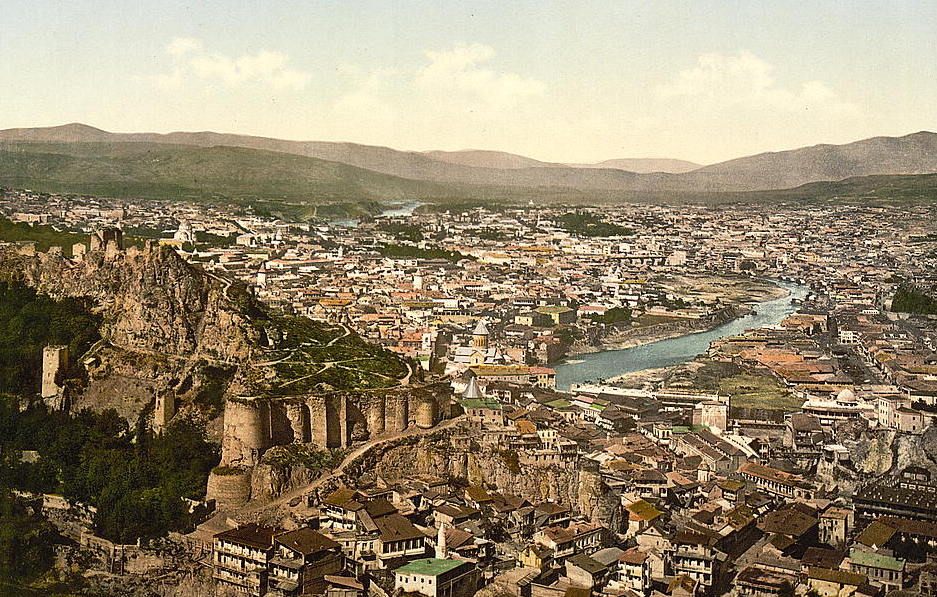

Georgia is a small country on the edge of many things. It borders Turkey, Armenia, Europe, and Russia. It is a mountainous country, and for many years, most of its people lived in high, remote areas. But it was also part of the Silk Road, the land-based trading route from China to Europe.

Wurdeman says the country’s harsh environment enabled the supra’s central role. “Georgians have this code of chivalry,” he explains. “There were obviously lots of wars going on; there were treacherous roads. People were walking long distances to get salt to trade or to take messages. The idea of being courteous and understanding to a traveler is rooted very deep.”

He explains that hospitality is valued even in extreme circumstances. “If a Georgian man showed up at Chechen man’s home, and he needed help as a guest, even if there had been an exchange of blood between the families, the Chechen family—because of this Caucasian code—would still receive them and protect them.”

Despite being invaded and occupied countless times, most recently by the Soviet Union, Georgia has preserved its culture and traditions. Darra Goldstein, a professor at Williams College who has authored a book on Georgia, believes supras and tamadas are a major reason why. During some supras, for example, Georgians burst into spontaneous polyphonic singing—an ancient choral harmonizing technique where independent melodies hauntingly intertwine with each other. “It’s a way of remembering history and the distinctiveness of Georgian culture,” she says of supras.

“It is definitely quite a thing to say we are Georgians. This might be Soviet Georgia; they might have dominion over us. But we are an ancient culture,” she states. “Our language predates Russian, our Christianity predates Russian, and we had a renaissance long before Western Europe did. We are an ancient culture.”

Even as Georgians leave the hills for cities and plug into globalization, Goldstein believes toastmasters will remain integral to Georgian culture. “This tradition has endured, but it doesn’t feel stagnant,” she explains. “It doesn’t feel like performa. It feels like it is still a vital part of how people perform feasts.”

Wurdeman says that young people in Georgia tend to conduct supras differently than their elders. There is less emphasis on the quantity of food and more on the quality; younger people are also more likely to allow women to act as tamadas. He thinks the supra’s flexibility and improvisational nature will keep it alive: While toastmasters almost always discuss death, history, and peace, every feast changes depending on who is presiding.

At the end of my feast with Djumbo, he addresses us individually. The night has been long, and the discussion has ranged from moments of hilarity to moments of quiet contemplation.

“You’re wonderful. You are happy and beautiful, and I wish you bright futures in your lives. That you achieve all your dreams,” he says. He talks about the dreams we shared with him, and then ends with a final lesson. “I hope for happiness in your lives,” he says. “I do not wish for you to have much money, because money only ruins people. May you lack for nothing. May you be fulfilled. May you be as happy in life as you are right now.”

For a final time, we raise our glasses and toast.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook