The Next Generation of a Rare Frog Captured in a Poetic Portrait

Embryos of one of the world’s most unusual amphibians become art in the eyes of a biologist and wildlife photographer.

Deep in northern Ecuador’s dense, humid cloud forests, at the very tip of a single frond of a single fern, the population of one of the world’s rarest frogs was poised to increase—hopefully.

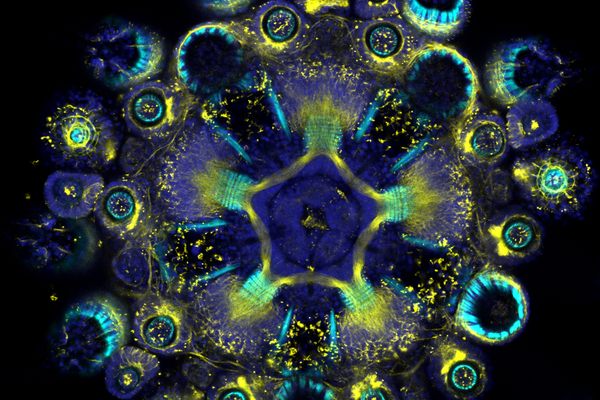

Photographer and biologist Jaime Culebras captured this backlit image of Wiley’s glass frog (Nymphargus wileyi) embryos near the Yanayacu Biological Research Station. The area immediately around the field station is the only known habitat of the frog, which was discovered in 2006.

Perhaps a day or so before Culebras photographed the frogs-to-be, a female deposited a clutch of eggs that were then immediately fertilized by a male. In the image, the developing embryos are kept safe from microbes and other threats by a gooey, gelatinous sack. The protective pouch will eventually drop off the frond and, with luck, land in the stream below, releasing the embryos into the watery environment they need to continue their development into tadpoles.

Some 20 varieties of frogs and other amphibians call the area around Yanayacu home, but the Wiley’s glass frog, which is only about an inch long, is special. Like most other glass frog species, which can be found in pockets of Central and South America’s cloud forests, N. wileyi is a tree-dweller that’s mostly green, with translucent skin on the underside of its body.

Having a see-through belly might sound like a terrible idea at first, as if you’re advertising to a predator the delicious cookies inside the jar. However, according to a 2020 paper published in PNAS, the translucent skin, when seen from below, creates a kind of camouflage called edge diffusion, which makes it harder for a predator to see the distinct, frog-shaped silhouette.

N. wileyi seems to take the opposite approach to disguising itself from predators above. The coloring on its back is pure green, without the spots or other markings that glass frogs generally have; N. wileyi also has almost no webbing between its digits. Webbing between fingers and toes makes amphibians more efficient swimmers, so the lack of it in N. wileyi, plus its leaf-like green camo when viewed from above, suggest it may be more fully adapted to life in the trees than other species.

There’s something else unusual about Wiley’s glass frog: Unlike other closely related species, which hide their eggs on the underside of leaves, N. wileyi females deposit their egg clutches topside, on the very tip of leaves—but only those that hang over streams, ensuring the maximum chance of success for their offspring.

While what researchers know about N. wileyi is intriguing, many details of the species remain unknown, including how many of these unusual little frogs are left.

Yanayacu Station is itself unusual, too. Less than 100 miles southwest of the busy capital of Quito, the station is nestled in a cloud forest near the Antisana Volcano. For more than 20 years, the station, started by American biologist Harold Greeney, has served as a field site for scientists running long-term studies on the area’s birds, invertebrates, and amphibians. But it also serves as a destination for artists and anyone else looking to reconnect with nature.

Culebra’s poetic image, Embryology, was named a finalist in this year’s BigPicture Natural World Photography competition.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook