Exploring Cuba, Guided by Graham Greene

‘Our Man in Havana’ was published at the end of 1958, and much of the city it describes remains intact.

“In Havana, where every vice was permissible, and every trade possible, lay the true background for my comedy.” — Graham Greene, Ways of Escape, 1980.

Ending up being detained in a rough, remote Cuban prison wasn’t really supposed to be part of the plan. My original idea was this: To explore Cuba, a nation suddenly on the brink of reconciliation with the United States, using the English author Graham Greene’s iconic 1958 spy novel Our Man in Havana as a travel guide. I’d track down the same locations, hotels, and bars he visited for inspiration, and hopefully gain some insight into the extent of Cuba’s inevitable transformation. True, about two-thirds of the way through the book, Greene’s protagonist does find himself apprehended by the Cuban police, but the story I had in mind was less windowless, concrete interrogation rooms and more sipping daiquiris in the Floridita bar.

A week before my encounter with la policia, I’d arrived at the José Martí airport on one of the first scheduled passenger flights from New York to Havana in more than 50 years, with a dogeared copy of Our Man in Havana. The comic novel tells the story of an English vacuum salesman posted to Cuba, who is reluctantly recruited as a spy by the British Secret Service, MI6. A hapless divorcee, James Wormold takes on the job mostly to secure his wayward, beautiful, and headstrong daughter’s financial future. Inventing a staff of agents and informants from the phone book and newspaper articles, Wormold begins to file creative intelligence reports and dreams up high-tech military installations based on vacuum-cleaner parts; all of which are hoovered up, as it were, by British intelligence.

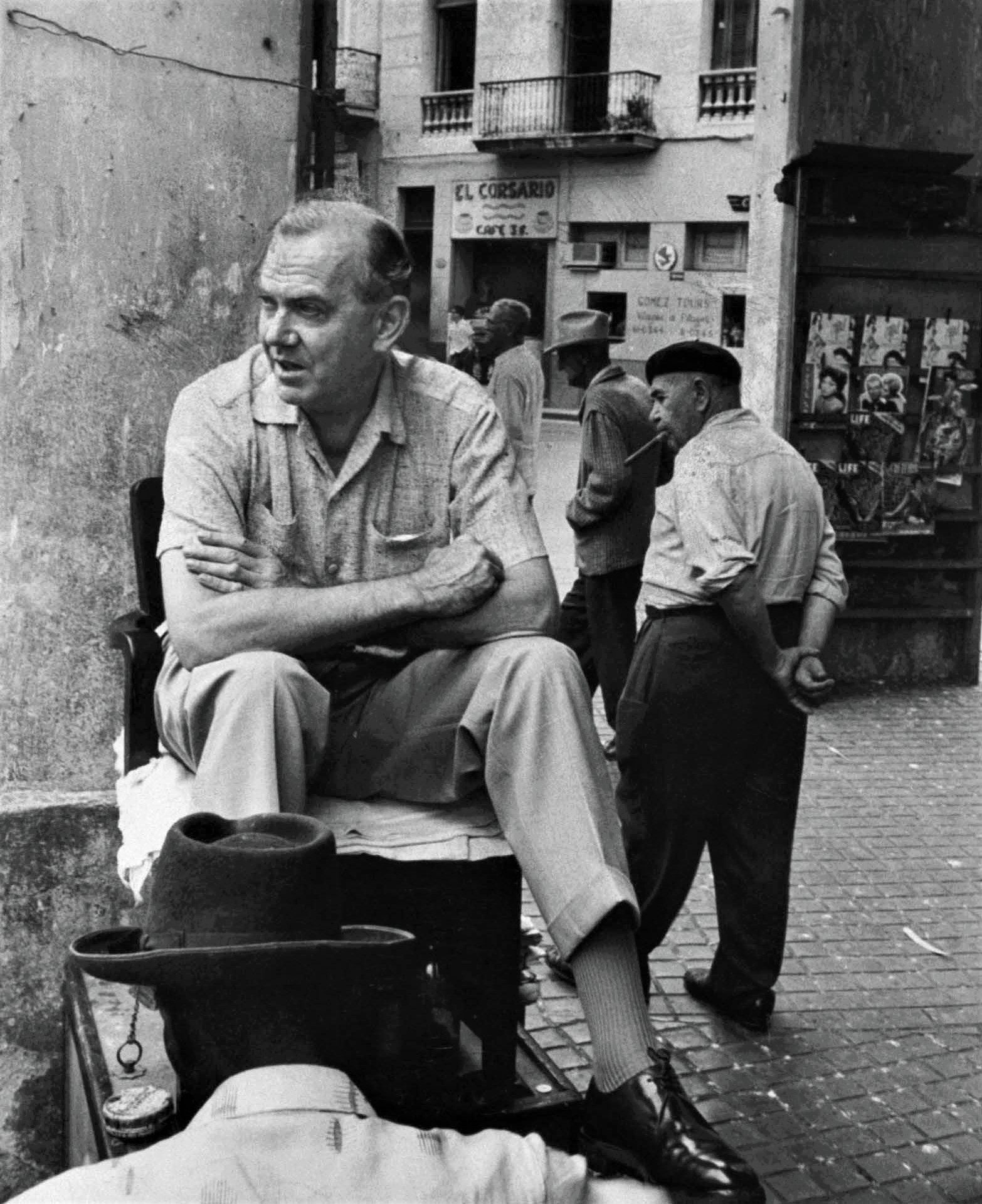

Greene himself didn’t necessarily set out to capture Cuba on the precipice of upheaval. He visited the country in the 1950s, and “enjoyed the louche atmosphere of Batista’s city,” when Havana was dominated by the American mafia, and rife with brothels, casinos, and saloons. At the same time, he became more intimately familiar with the realities of Batista’s Cuba. Greene sympathized with the rebels so much he ended up trafficking warm winter clothing to Fidel Castro’s men camped in the mountains, befriending Castro in the process. Our Man in Havana was published in October, 1958; three months later, Castro descended from the Sierra Maestra to finally seize Havana.

The outside view of Cuba is that it still hasn’t changed much since then. It has long been an island, as Christopher Hitchens described it, “stranded in time and isolated from many recent currents of history and political economy… the city of Havana has been compelled to remain very much as Greene described it.” Using Greene’s novel as a reference point would therefore be the perfect snapshot, a literary guide to a Cuba frozen in the late 1950s.

Traveling to Cuba from the United States is still technically prohibited, although the Department of Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control has issued licenses to travel for 12 categories; I was traveling for ‘journalistic activity,’ but in reality no one in Cuba asked why I was there. Passing through passport control, I passed a line of wooden desks manned by nurses in pristine, white dresses collecting health questionnaires handed out on the plane (also not checked). My taxi driver, Elliot, had studied civic law and practiced in Havana for six years, but had turned to shuttling visitors to and from the airport as it earned him more money. It also helped him practice his English, which is not widely taught in Cuba. We made our way into Old Havana.

When Americans think of Havana, the first things that spring to mind are the music, the 1950s cars, and the faded pastel buildings. Up close, the first impression you get is of the noise—crowded narrow streets thronging with wild dogs and cats, street hawkers selling cigars and rum, bells and music blaring from the pedal-taxis. Elliot hadn’t heard of Graham Greene, but he loves “Ernesto,” Cuba’s favorite adopted literary son. Dropping my bags at the casa particular where I was staying, part of a government authorized program where families can rent out rooms in their homes, I made the one block walk north to Lamparilla Street.

Stretching lengthways across the entire breadth of the teeming Vieja Habana, Lamparilla Street is the fictional home of Wormold’s vacuum cleaner shop. It’s from here that he futilely tries to sell ‘Atomic Pile’ suction cleaners to the residents of Havana, and it’s here that he first encounters Agent Hawthorne of MI6. Greene has Wormold living at number 37, but walking down Lamparilla Street, I discover that the numbers skip from 35 to 39, number 37 disappearing much as Hawthorne does after the initial approach, into “the square at the top of Lamparilla Street… swallowed up among the pimps and lottery sellers of the Havana noon.”

Much of Our Man In Havana takes place, as do many of Greene’s novels, in the friendly confines of a bar. Wormold’s principal haven is the Wonder Bar, my next stop. Fortunately, Greene provides exact directions: the corner of Virtudes and the Paseo. Greene even describes how long it should take to get there from Wormold’s shop:

“Seven minutes to get to the Wonder Bar; seven minutes back to the store; six minutes for companionship. He looked at his watch. He remembered that it was one minute slow… By the corner of Virtudes, Dr. Hasselbacher hailed him from the corner of the Wonder Bar… Wormold turned into the bar from the Paseo.”

Starting at number 35, I headed west through the old city, and seven minutes later, did indeed end up at Virtudes street, only to find no Wonder Bar. The only wondering I encountered was whether anything in Greene’s nearly 60-year-old novel would actually exist.

Graham Greene’s life spanned most of the 20th century. He was also, according to William Golding, “the ultimate chronicler of 20th-century man’s consciousness and anxiety.” An insatiable traveler, he was drawn to what he called “the world’s wild and remote places,” often finding himself in aging colonial outposts on the brink of violent upheaval, preferably with a well-stocked bar at the end of it. His travels to the former French Indochina (now Vietnam), Haiti, Sierra Leone, Mexico, and Cuba formed the inspiration for some of his greatest books. He worked as a journalist, author, film critic, and spy, vividly portraying rumpled, disillusioned Englishmen, often in romantic upheaval, but always nursing a bottle of whiskey.

Not to be deprived of a ‘cooling morning daiquiri,’ I headed up the Paseo in the direction of another of Wormold’s havens, Sloppy Joe’s. The Paseo is a wide, European style boulevard, a promenade lined with palm trees and marble benches that separates the faded Spanish Colonial grandeur of the Vieja Habana from the sprawling tenement slums of the Centro neighborhood, until it reaches the sea. Once the promenade had been lined with opulent mansions, theaters, and American car dealerships, all of which are now mostly closed and lying in ruins.

Sloppy Joe’s opened in the 1930s, and featured one of the longest mahogany bars to be found in the Americas. An oasis from the humidity of the sweltering city, the 60-foot bar was as much a haven for American celebrities such as Clark Gable and Spencer Tracy as it was for regular tourists enjoying a break from Prohibition back home. The Los Angeles Times once described it as enjoying “the status of a shrine,” and its long cocktail list and sumptuous, dark decor wouldn’t have looked out of place in a Fifth Avenue hotel bar in Manhattan.

“For some reason that morning he had no wish to meet Dr. Hasselbacher for his morning daiquiri… so he looked in at Sloppy Joe’s instead of at the Wonder Bar. No Havana resident ever went to Sloppy Joe’s because it was the rendezvous of tourists; but tourists were sadly reduced nowadays in number, for the President’s regime was creaking dangerously towards its end.”

In Greene’s book, this is where Wormold is approached by Hawthorne to become an agent for the British Secret Service. But like most things associated with the excesses of American influence, Castro had the iconic bar first nationalized, and then finally closed in 1965. For decades, the opulent columned building, like much of Havana, was gradually allowed to fall apart.

However in 2007, restoration work began on the bar, overseen by the Office of the City Historian of Havana. Using archival photographs, Sloppy Joe’s was painstakingly restored, reopening in 2013 looking almost just as it did when Ernest Hemingway and Graham Greene drank here. For Eusebio Leal of the City Historian’s Office, “what interests me is to work to restore my city… a whole series of things that form part of its memory… the final objective is not commercial, it’s not to exploit a name. The opportunity it brings is to recover an important memory of Havana.” The frozen daiquiris are excellent by the way, but just as Greene described over 50 years ago, there were no Havana residents enjoying them.

A few blocks farther down the Paseo is the grand old Hotel Sevilla. Opened in 1908, the 10-story pastel pink hotel features a glittering rooftop ballroom designed by the New York architectural firm responsible for the Waldorf-Astoria and the Grand Ballroom of the Plaza Hotel. It is amid these imposing confines, in room 501, that Wormold finally accepts Hawthorne’s approaches to become a paid spy for Great Britain, taking on the code name 59200 stroke 5. He’s given a copy of the children’s book Tales From Shakespeare by Charles and Mary Lamb to use as a cipher.

Like Sloppy Joe’s, the Hotel Sevilla is also being renovated. For a cash-strapped economy like Cuba, tourism is a vital source of income, and preserving Old Havana, one of the jewels of the Caribbean Spanish Colonial crown, has become imperative after decades of neglect.

“All going well?”

“I think we’ve got the Caribbean sewn up now sir, Hawthorne said… I was more uncertain at first about 59200 stroke 5.”

“Stroke 5?”

“Our man in Havana, sir. I didn’t have much choice there, and at first he didn’t seem very keen on the job. A bit stubborn.”

“That kind sometimes develops best.”

As British intelligence falls for Wormold’s imaginary reports, Greene’s novel begins to lampoon the bumbling, outdated service for which he’d worked undercover in Sierra Leone during World War II. A far cry from fellow intelligence employee Ian Fleming’s depiction of the debonair world of 007, Greene’s Secret Service, as Hitchens writes, is “a place of crumbling scenery and low comedy, populated by a cast of jaded misfits.” Wormold’s creative talent for inventing intelligence reports based on the inner workings of his vacuum cleaners proves such a success in London that MI6 increases his staff with a radio operator and a female code-breaker, Beatrice, with whom he develops a romance.

“After supper they walked back along the landward side of the Avenida de Maceo… the rollers came in from the Atlantic and smashed over the sea-wall. The spray drove across the road, over four traffic-lanes, and beat like rain under the pock-marked pillars where they walked. The clouds came racing from the east, and he felt himself to be part of the slow erosion of Havana.”

The Avenida de Maceo is more commonly known today as the Malecón, and was my next port of call. If Paris has the Champs Élysées and Manhattan has Broadway, so Havana has the Malecón. One of the world’s great thoroughfares, it stretches for five miles along the northern coastline. It is the soul of Havana, teeming with fishermen, musicians, and lovers rendezvousing on the long sea wall, set against a backdrop of vast, crumbling mansions.

“The pink, grey, yellow pillars of what had once been the aristocratic quarter were eroded like rocks… the shutters of a night club were varnished in the bright crude colours to protect them from the wet and salt of the sea.”

All four traffic lanes are filled with vintage cars. I’d expected to see a few of the iconic 1950s American automobiles that grace the covers of every guide book to Havana, but I didn’t realize just how many there are. Virtually every second car is a brightly colored, lovingly cared for, hulking behemoth of vintage U.S. steel. I was traveling westwards along the Malecón in a taxi, a beautiful, eggshell blue Buick convertible dating to 1952, at least twice as old as its proud owner, Jordanka.

We were heading in the direction of one of Havana’s rare jewels that has remained beautifully preserved, the illustrious Hotel Nacional de Cuba. Built by New York’s most prestigious architectural firm, McKim, Mead & White, the Nacional looms large in Havana’s recent history. It’s perched high on a hill, at the site of the old Santa Clara Battery, overlooking the Malecón and Havana harbour. A hotel of refined, Art Deco elegance, the Nacional opened its doors in 1930 to such illustrious guests as Ava Gardner, Rita Hayworth, Sir Winston Churchill, and Errol Flynn. This is where the historic Havana Conference of 1946 convened, the infamous meeting of the heads of the U.S.-based mafia.

In Greene’s novel, the Nacional is the site of a trade meeting where enemy agents attempt to poison him.

“He made his way through the lounge of the Nacional Hotel between show-cases of Italian shoes and Danish ashtrays and Swedish glass and mauve British woolies.”

Today, in stark contrast to much of crumbling Havana, the Nacional is a gleaming, elegant jewel where peacocks roam the lush gardens and waterfalls overlook the ocean. It’s also where the nightly room rate costs close to the average monthly wage in the city.

A peculiar relic of pre-war ostentatiousness, the Tropicana Club, located in the swish suburbs, is a remarkable throwback to the 1950s, when Cabaret Guide described it as “the largest and most beautiful night club in the world.” This is where Wormold hosts a party to celebrate his daughter’s 17th birthday. Greene describes the lurid exhibition:

“It was a more innocent establishment than the Nacional in spite of the roulette-rooms, through which visitors passed before they reached the cabaret. Stage and dance-floor were open to the sky. Chorus-girls paraded twenty feet up among the giant palm-trees, while pink and mauve searchlights swept the floor. A man in bright blue evening clothes sang in Anglo-American about Paree.”

Today the Tropicana still regularly hosts glittering cabaret shows, where guests are entertained by extravagantly plumed and bejeweled ‘las diosas de carne’ (the goddesses of the flesh).

If the Tropicana has endured in an atmosphere of 1950s kitsch, sequins, and Desi Arnaz, the next stop on my Graham Greene tour was a big change of pace: Centro Habana and El Barrio Chino. Tourists may largely stick to the bustling Old City, but to the other side of the Paseo lies these two densely populated areas. Here, the idea of there being money to spend refurbishing historic Havana feels more like a distant dream. Street sanitation is virtually nonexistent. Homes are crumbling as much as the roads that pass by them.

When Wormold’s elaborately invented web of spies and subterfuge starts to unravel, and his unwitting network of subagents begin to attract the lethal attentions of his Soviet counterparts, he descends into the depths of the Centro to rescue a stripper by the name of Teresa. Thanks to a combination of energy-efficient streetlamps alongside regular electricity shortages, even today being here at night feels like stepping into a film noir.

“The night was hot and humid, and the greenery hung dark and heavy in the pallid light of the half-strength lamps.”

I was headed in the direction of the former location of the long-closed Shanghai Theater, one of pre-revolution Havana’s most notorious clip joints. Even during the naivety and innocence of the 1950s, the Shanghai was modestly billed as ‘the world’s rawest burlesque show.’ The Shanghai closed in the wake of Castro’s revolution. But walking along Zanja Street, and through the narrow, cramped tenements of the Centro, is in many ways to experience the real Havana—the dark streets, swamped with friendly, chattering people; the corner bars lit by glaring fluorescents, each one packed with musicians playing traditional songs; the air thick with tobacco, mint leaves, sugar, and rum.

“The time arrived for his annual visit to retailers outside Havana, at Mantanzas, Cienfuegos, Santa Clara and Santiago… before leaving he sent a cable to Hawthorne. ‘On the pretext of visiting sub-agents for vacuums propose to investigate possibilities for recruitment… calculate expenses of journey fifty dollars a day.”

And so like the enterprising amateur secret agent of Greene’s imagination, I left Havana, heading south in the direction of Cienfuegos, to see more of what is a surprisingly vast country. (Caribbean islands are generally thought of as small, but Cuba has a larger land area that Massachusetts, Vermont, Rhode Island, New Jersey, and Connecticut put together.) Driving through Cuba, it takes a while before you realize that there are virtually no advertisements anywhere. There are billboards, but relatively few, and close inspection shows them all to be government propaganda.

My destination was Trinidad, a charming colonial town on the coast, five hours southeast of Havana. If Havana is said to be trapped in the 1950s, Trinidad is largely stuck a century before that. Once a thriving town built on the sugar and slave trades, Trinidad has remained one of the best-preserved Spanish Colonial hamlets anywhere. Horses and carts are as common as vintage cars, if not more so. Family homes date from as far back as the early 19th century, while the town’s squares are decorated with the mansions of former plantation owners, churches, and fountains. One of the few harsh reminders of more modern concerns are the remnants of an American U-2 spy plane shot down and exhibited in the Casa de los Conspiradores.

It was amid these lush surroundings, in the mountains of Sancti Spíritus, that I found myself detained by the police. In Our Man In Havana, Wormold is apprehended for breaking a late-night curfew. I’d booked a taxi back to Havana to be shared with two strangers, a pair of Cypriot tourists, and manned by a young driver. Upon approaching a routine checkpoint, our driver decided the best course of action was not to slow down, as indicated, but rather to floor the gas pedal, leaving la policia covered in dust.

About 15 miles outside of Trinidad, a bucolic stretch of Caribbean coastline, two police cars formed a more effective barricade across the road. Sparing any niceties, the police roughly grabbed the driver from behind the wheel, slapping on handcuffs and pushing him against the hood of the car, leaving myself and the two Cyprus lads somewhat bewildered as to what was going to happen. With no cell phone coverage and limited Spanish, we waited by the side of the road for three quarters of an hour until another police car picked up the taxi and drove us all to a nearby police station. At first we thought we were going to be allowed to carry on our journey, but the police refused to open the locked trunk of the taxi so we could get our bags, keeping us detained.

The interior of this rural Cuban police station was rudimentary, but teeming with people. Its concrete walls were bare save for posters of Castro, with holding cells in the back and a sparingly furnished front room. We were asked to write a report of what had happened, but with little Spanish, no phone, I refused to write or sign anything. After three or four hours, during which our driver was somehow allowed to wander around the police station on his phone, we are finally allowed to leave. Finding a nearby official taxi service, we restarted our five-hour journey back to Havana.

The first place I headed to on reaching the suddenly safe-feeling capital was the Floridita Bar. Located at the far end of Obispo Street, it is known as la cuna de la daiqiuri, or ‘the cradle of the daiquiri.’ The Floridita’s literary connections are strong: Hemingway still holds the record for daiquiris consumed in one sitting (allegedly, 16) and his presence looms large, especially via a lifesize bronze statue that holds down one end of the bar, where he looks out genially at visitors with a glint in his eye. In Our Man In Havana, the Floridita is where Wormold meets his first wife for the first time. The plush red decor matches the tailored jackets sported by a first-rate bar staff. Sipping a daiquiri, I reflected on where I’d found myself that morning.

Graham Greene’s novel was published at the end of 1958, and remains one of his most popular books. The Havana he describes is, remarkably, largely as it was: a beguiling island, at least for now, frozen in time.

Ready to explore Cuba and its fascinating history for yourself? Join Atlas Obscura on our upcoming Hidden Havana trip! Details here.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook