Why Ancient Greek Temples Were Full of Disembodied Clay Limbs

Arms and legs and eyes and ears and genitals, oh my!

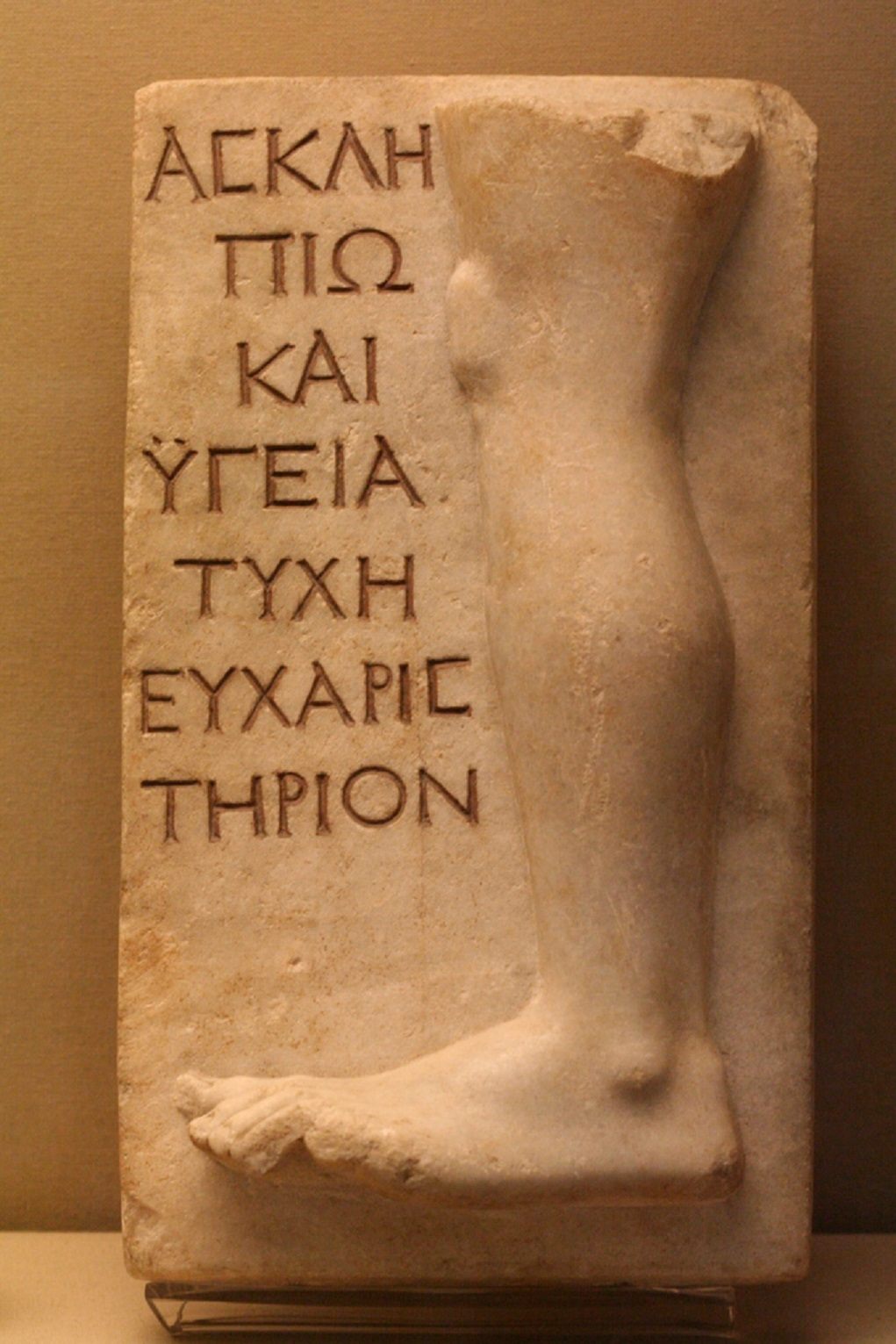

In ancient Greece, guys with STDs didn’t have a ton of options when it came to medical treatments. Sick people often had no recourse other than to appeal to Asclepius, god of health and medicine. They’d go to his temples, and after Asclepius “cured” them in exchange for an offering or a fee, grateful supplicants dedicated votive reliefs in the shape of the body part he healed. As a result, archaeologists have found many terracotta carvings over the years of Ancient Greek legs, arms, ears, or, yes, even penises.

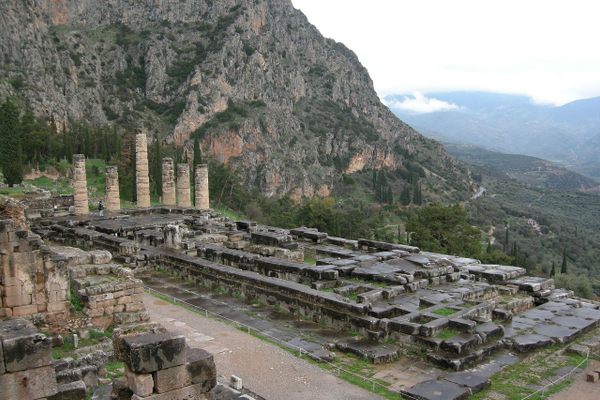

It’s believed such carvings either commemorated successful healings or were requests to get Asclepius to pay attention to ailing limbs. They would have been hung in the sanctuary—called an Asclepeion—in a public area, so visitors could see just how good at his job Asclepius was. Models of genitals, breasts, eyes, ears, and limbs were pierced and hung from the ceiling; reproductions of larger portions of the body, such as torsos or entire heads, were put on shelves.

In a process called incubation, patients would sleep overnight in a room dedicated to healing, known as an abaton; Asclepius, they believed, would then help either “by direct intervention (laying on of hands, applying medicines, even performing surgery) or indirectly by sending a dream in which he recommended a treatment,” as the classicist Steven M. Oberhelman writes in the Athens Journal of Health. In the ancient world, there wasn’t the same division between what modern scholars define as professional medicine (i.e., a practicing doctor) and “popular medicine” (think homeopathic healers and herbalists, charm-sellers and magicians). And it’s worth noting that Asclepius wasn’t the only deity believed to have magical healing powers.

Some sanctuaries may have specialized in healing certain diseases. According to Oberhelman, 40 percent of the votives found at the Athenian Asclepeion depicted eyes, indicating visitors often asked for help with ophthalmic issues. At Corinth, most of the models were of hands and feet, perhaps reflecting agricultural injuries to local farmers, and genitals, suggesting that Corinthians may have suffered in particular from sexually transmitted diseases.

At the Asclepeion in Epidaurus, the iamata, or patients’ chronicles of how Asclepius cured them, were inscribed on stelae, probably by priests; although some scholars debate these stories’ factual reliability, they remain fascinating chronicles of the belief in dream healing in Ancient Greece. One iamaton reads: “Hermon from Thasos. This man, who was blind, he healed. When he did not subsequently bring the healing fee, the god again made him blind. When he came back and slept in the sanctuary again, he healed him.” One woman named Nikasibula was “sleeping for children,” meaning she was asking the god to heal her infertility. Her night in the abaton found her dreaming of Asclepius coming to her, “bringing a snake slithering with him. She had sex with it.” As a result of this dream, Nikasibula reportedly gave birth to two boys within the year.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook