The Mystery of ‘Harriet Cole’

In 19th-century Philadelphia, an anatomist dissected and mounted a human nervous system. Now researchers are trying to figure out whose remains are stretched out in a glass case.

If “Harriet” could hear, she might pick up the sound of ping-pong balls skittering across a table. If she could smell, she might detect a range of lunches being reheated in a nearby microwave. If her eyes could see, she might let them wander a busted Pac-Man machine, a TV, and a campus bookstore, decorated with a swooping, celebratory paper chain, like an elementary-school version of DNA’s double helix. She might even catch a glimpse of herself in a camera lens or an observer’s glassy eyeballs. People often stop to stare.

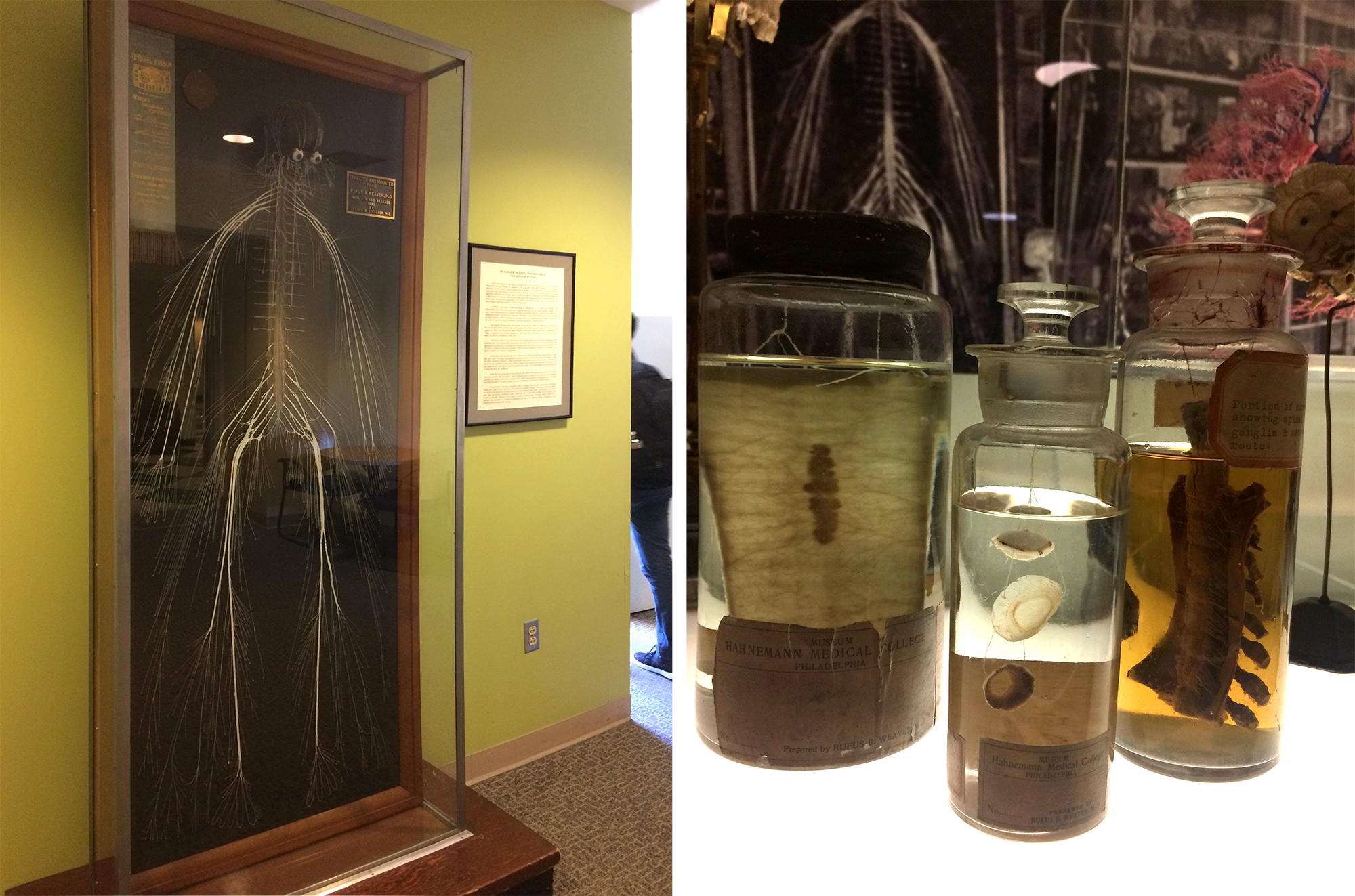

On a sweaty Saturday, before social distancing was the law of the land, a group of visitors gathered at Drexel University’s medical campus in Northwest Philadelphia to meet “Harriet.” The preamble to this encounter was a display case holding several unusual and meticulously prepared medical specimens, long used as teaching tools. Like “Harriet,” each had been created in the late 19th century by a star anatomist, Rufus Weaver. Now, behind glass, between the cadaver lab and a bookstore, a segment of intestine and a piece of a spinal cord sit in stillness. A dissected eyeball floats ethereally in century-old liquid, its separated parts looking like a tiny jellyfish, a bit of brittle plastic, a mushroom cap.

The visitors shuffled through the door and into the otherwise empty student center. They huddled on the low-pile carpet, nondescript in the style of a suburban office park, and peered at more of Weaver’s dissection work, which occupied a glass-fronted case. They surveyed a sinewy hand, ropey and purplish. Two skulls and necks. Then, “Harriet.”

Reactions rippled.

“Oh.”

“Oh, wow.”

Quietly, “Poor Harriet.”

“I’ve been meaning to find her,” said Malaya Fletcher, an epidemiologist in Washington, D.C., specializing in infectious disease. Fletcher remembered learning about the dissection in her high school biology class, and the story had stuck with her. “It’s just awesome,” she said. “You almost don’t believe it’s real.” The group crowded in close, lofting their cell phones above each other’s heads. They bobbed and weaved their raised hands, trying to take pictures without capturing their own flushed faces reflected in the glass.

“Harriet” is a network of fibers fastened to a black board in a case pushed up against a wall. At the top, there appears to be a brain, plump and brown, and a pair of eyes. Scan your own eyes down and you’ll encounter an intricate system of skinny, brittle cords, pulled taut and painted startlingly, artificially white. The outline is recognizably human—there’s the impression of hands and feet, the hint of a pelvis, the suggestion of a rib cage—but it is slightly fantastical, too. The way the cords loop at the hands and feet, it almost appears as if the figure has fins. Elsewhere, the fibers look shaggy, like chewed wire, as if electricity is shooting from the margins of the body.

This is a human medical specimen, in the spirit of an articulated skeleton. But unlike that familiar sight, it represents the nervous system, a part of the body’s machinery that most people have trouble even imagining. Some who stand before “Harriet” wiggle their fingers and toes, as if trying to map the fibers onto their own bodies and make the sight somehow less abstract.

Neighboring the display is a label that identifies the specimen as “Harriet Cole” and explains that she was a Black woman who worked as a maid or scrubwoman in a university laboratory at Hahnemann Medical College, died in the late 1800s, and donated her body to the medical school. Her nervous system, the story goes, was dissected by Weaver, then preserved and mounted as a teaching tool and masterpiece of medical specimen preparation.

Before the preparation wound up at this campus, more than a decade ago, it traveled to Chicago for the 1893 World’s Fair, where it won a blue ribbon. It starred in a multi-page feature in LIFE magazine and took up residence in academic textbooks. But before all of that—before the nerves were naked—the fibers animated and stimulated a body. In 2012, the university’s press office characterized the nerve donor as the school’s “longest-serving employee.”

At the time of the dissection, no one paid much attention to the person whose circuitry had been harvested for this act of scientific and anatomical bravado. The story of “Harriet” emerged over the following decades, and swirled with mythology that calcified into fact. The specimen and the mythology surrounding it are marvelous and rattling, revealing how systemic inequalities endure into the afterlife, how “great” white men have propped themselves and each other up on the bodies of women, and how stories take root. How truth—like a pickled specimen on a forgotten shelf—can shrivel, bloat, or cloud with age, until it’s hard to decipher at all.

The history of medicine in the West is littered with unsavory and violent episodes, from coerced experiments to botched or brutal treatments to patients made into spectacle—practices that would widely be considered horrific today. Some historians argue that there’s little to be gained from viewing the past through the lens of today’s mores; instead of applying contemporary ethics to a past era, they suggest, viewers should sit with any discomfort they feel about that craggy terrain between what was once unremarkable and what would now be condemned. Others, including a trio of medical historians at Johns Hopkins, writing in The Lancet in October 2020, insist that wrestling with historical horrors helps illuminate persistent inequalities in terms of medical access, treatment, and more.

Alaina McNaughton and Matt Herbison are citizens of that land, bordering past, present, and future. McNaughton and Herbison are public historians, archivists, and educators. At the time of the group visit, both worked at Drexel’s Legacy Center, which holds and interprets the institution’s archives, plus those of other schools it has absorbed. (McNaughton has since departed for another job.) Both are history nerds with a librarian’s attention to detail and a novelist’s love of a good yarn, and their work requires them to describe and contextualize the past through primary sources. “Harriet Cole” is among the most visible, puzzling, and challenging artifacts of the school’s long history.

Researchers such as Herbison and McNaughton are neither anatomists nor ethicists: They didn’t elect to procure, dissect, and display a body, though they inherited the finished product. As caretakers of this object, they have accepted the mission of poking around in the historical record, cleaving fact from fiction, trying to piece together a fuller story of “Harriet Cole” in spite of official records that often omit women and people of color.

A few months before that group visit, Herbison and McNaughton stood in front of the display and narrated the task they had taken on. They pointed to the wall text, the metal-tasseled World’s Fair ribbon, the carved bust of Weaver, eyes fixed forever on the middle distance. Herbison, who is in his mid-40s and wears thin glasses, crossed his arms tightly across his chest while he stacked his thoughts, one upon another, like vertebrae. McNaughton, younger and wearing bobbed red hair and vaguely cat-eye frames, cradled her chin in her hand as she examined the case.

Committed to resurfacing stories of women lost, warped, or overlooked in the archives, McNaughton, Herbison, and other collaborators, including medical historian Brandon Zimmerman, are trying to pin down specifics about “Harriet.” They’re wondering, more than 130 years later, how to describe the dazzling, jarring preparation, stripped of skin and pulled away from the bone. Whose body this is, and what would it mean if one of the university’s oldest fixtures never knew that she would spend her afterlife on display?

“I’ve started putting a little more intentional dubiousness behind, for example, what it says on the label,” Herbison said. “Sometimes I’ll say, ‘The nervous system preparation that has long been known as Harriet.’” He held his fingers in the air to put scare quotes around “Harriet.”

“So, she donated her body,” Herbison said. “Well.” He paused for five seconds. “We don’t know.”

Your nervous system works hard, crackling with electrical energy, and never goes off the clock. Fibrous bundles of nerves cluster in your brain and spinal cord and then branch and branch and branch the length of your body, carrying messages back and forth. Inside these fibers, cells called neurons speak to other cells around your body. Scientists estimate that there are tens of billions of neurons clustered in the brain, and some 200 million or more in the spinal cord. Messages travel through this network via skinny fibers known as axons, and the path isn’t smooth—the highways are broken up by little curbs, of sorts, called synapses. To continue on their way, dispatches must leap across them, and when they do, your body releases chemicals called neurotransmitters. This is how you triage sensory stimuli: Move your finger to touch the hot pan. Feel the pain light up. Yank it away.

Scientists have only understood neurons for a few centuries, and puzzling out how they communicate with chemicals and flashes was an additional challenge. The Spanish neuroscientist Santiago Ramón y Cajal and Camillo Golgi, an Italian, shared the 1906 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine for their dueling ideas about the structure and behavior of the human nervous system. Golgi—like the German anatomist Joseph von Gerlach—contended that all nerve cells clung together; eventually, Cajal proved that there are small gulfs between them, and that impulses hopscotch from one to another.

Before we knew any of this, however, many suspected that there was a connection between the brain and the rest of the body. In the second and third centuries, the Greek physician-philosopher Galen dissected his way through sheep, weasels, monkeys, and an elephant, and extrapolated some components of the human nervous system. In the 14th century, Persian anatomist Mansur ibn Ilyas sketched a colorful version of it in his Tashrih-i Mansuri. Renaissance thinkers such as Vesalius probed further, and a picture of the branching system began to take form in ever greater detail. By the 18th century, other anatomists had described additional aspects: The Scottish surgeon John Hunter, for instance, detailed the olfactory nerves; his brother, William, founded an anatomy school where students and researchers examined the spinal cord. By the time the elven, headstrong anatomist Rufus Weaver found himself obsessed with the human nervous system in the late 1800s, the nerve network wasn’t alien terrain. But few had roamed it the way Weaver would.

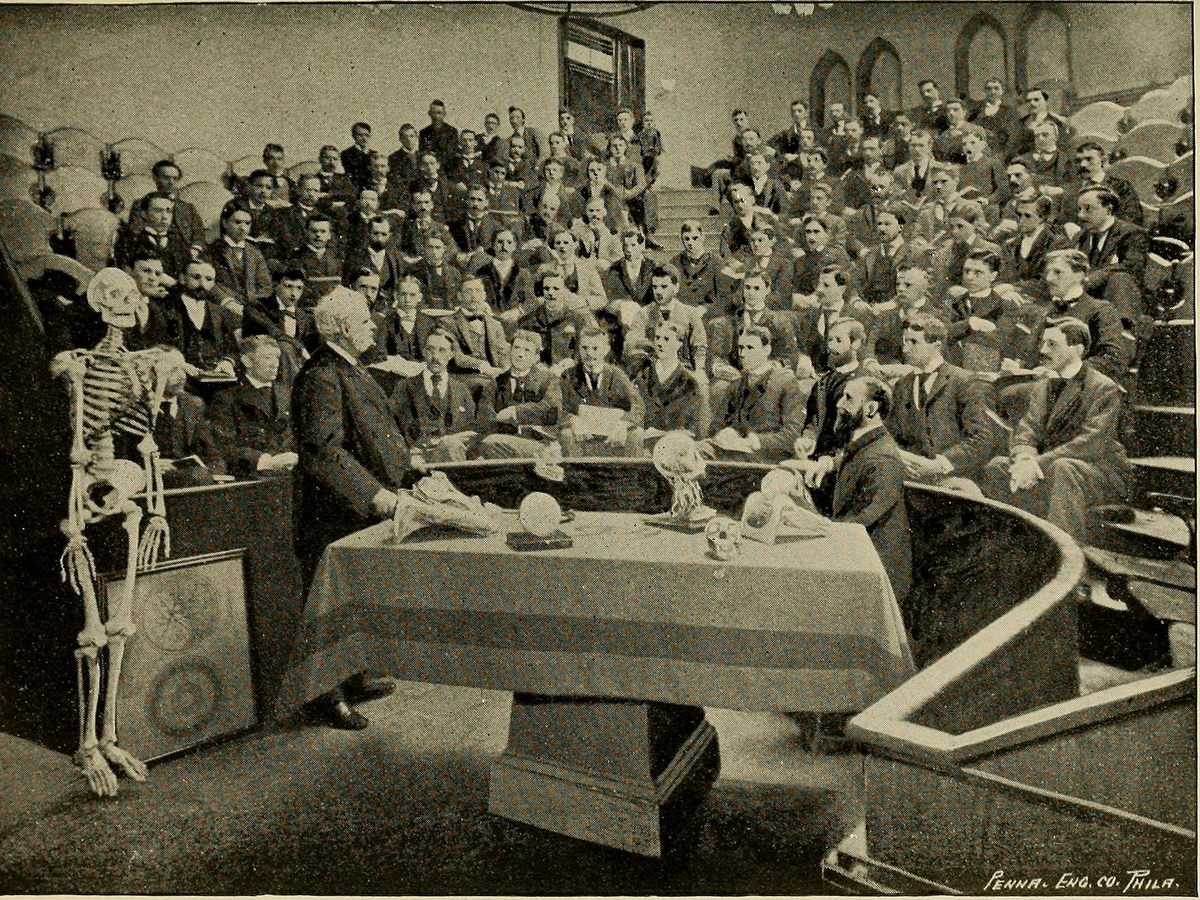

Born in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, in 1841, Weaver wore his hair slicked, with a precise, almost surgical, part, and groomed his dark beard to a sharp point. Before arriving at the homeopathic Hahnemann Medical College in 1869, Weaver studied at Pennsylvania Medical College and took courses at the University of Pennsylvania and Jefferson Medical College. (Hahnemann Medical College eventually became Hahnemann University, and in the 1990s, the medical school merged with the Medical College of Pennsylvania. By the end of that decade, the combined school was subsumed into Drexel University, which is why Weaver is a person of interest in the institution’s archives today.) In the aftermath of the Civil War, Weaver was dispatched to exhume and attempt to identify and relocate the corpses of more than 3,000 slain Confederate soldiers. He had a knack for anatomy, a keen eye for detail, and a high tolerance for viscera.

At Hahnemann, Weaver was appointed custodian of the university’s anatomical museum in 1880, and busied himself assembling an anatomical wunderkammer with no rival. Gone were papier-mâché models and “musty,” dried-out specimens. Weaver filled the light-flooded, third-floor space with hundreds of new medical displays, many of which he prepared himself. His trove included bladder calculi, sections of healthy and diseased brains, and an entire uterus, partly consumed by a tumor and opened to reveal a six-month-old fetus. The anatomist imagined these—and the museum’s hundreds of other objects—as teaching tools instead of “mere ‘curiosities,’” according to an announcement circulated in the mid-1880s. Among the assortment, there was Weaver, described in 1902 by a reporter from The North American as a “little professor” brimming with “energy, originality, and vim,” “as cheerful and bright as a May morning,” and prone to speaking of his collection of “beautiful tumor[s]” with tenderness and awe. (“Here is a lung,” the reporter quoted him saying. “Isn’t that the handsomest thing that you ever saw?”) In one 19th-century photograph, Weaver poses next to a fresh cadaver, its chest pried open, while limbs dangle around it like cuts of meat in a butcher’s shop. The anatomist’s own bearing was stick-straight—perhaps an occupational hazard of standing above so many spinal columns.

It was only when he set out to dissect and display, intact, an entire human nervous system that Weaver’s colleagues thought him mad, or soon to be. For years, Weaver had struggled to teach the intricacies of the nervous system to his students. It was a doozy. Students “would come to their final examination well posted on bones, muscles, vessels and viscera,” a contemporary later recalled, “but lame and halting on the brain and nerves.” Weaver wanted a clearer way to drill them on the anatomy.

When he turned to Europe for answers and found none, Weaver resolved to create one himself. Back in Philadelphia, he told a colleague, A.R. Thomas, an esteemed anatomist and dean of the college, about his idea to dissect an entire human body down to the raw nerves. Weaver was seeking counsel or support, but got a wagging finger. Thomas and a slew of other colleagues “objected strenuously,” recounted Philadelphia physician William Weed van Baun in remarks delivered at a celebration in Weaver’s honor in 1915. The skeptics were convinced that the project was foolish or even reckless—likely to “ruin [Weaver’s] sight or cause a breakdown,” van Baun continued.

Weaver was undeterred. And in the spring of 1888, he selected a subject.

The preparation that would later come to be known as “Harriet Cole” began with “a female subject about thirty-five years old, with moderate adipose development,” wrote Thomas, who, for all his rumored naysaying, is one of the few sources we have for what Weaver did next. Prior to dissection, the corpse had “previously [been] injected with chloride of zinc,” Thomas recounted, sometimes used as a disinfectant.

The cadaver apparently floated in a vat for a while, and then Weaver got to cutting. We can’t take his word for how he proceeded, because he never committed that to paper. “The dude loved to prep, and that’s about it,” Herbison says. (On the occasion of Weaver’s 90th birthday in 1931, a reporter noted that “[he] has turned aside all pleas to write treatises or articles and it has been said that his wide-spread knowledge will die with him.”) Much of what the archivists have learned about Weaver’s life comes from an overstuffed 1916 scrapbook—one of several pieced together by Thomas Lindsley Bradford, a lecturer and librarian at Hahnemann who compiled articles, photographs, and assorted ephemera about Weaver and the school’s other famous homeopaths. The raft of material contains no first-person account of Weaver’s technique.

In the 20th century, once scientists were able to isolate strands of DNA, a life-sized model of the nervous system went “from being state-of-the-art to antiquated,” says Brandon Zimmerman, a medical historian and manager of public programs at the Legacy Center. When DNA ensnared the attention of scientists, curators, and the general public, dissections no longer seemed quite so awesome and useful by comparison.

This particular preparation was likely spared by some combination of its function as a teaching tool and a little lucky or affectionate abandonment; it apparently spent some time in a mailroom and a closet over its long afterlife. Similarly, other old Weaver specimens have turned up over the years, hiding in plain sight. Between 2016 and 2018, Zimmerman arranged for several trips to Hahnemann to see if there were any old objects to recover. On one visit, he found the gold plaque that once marked the entrance to Weaver’s museum, sitting on the floor and serving as a doorstop. On another, he unearthed a Weaver dissection—a human hand, splayed in the sort of plastic container that might hold a heap of fries from a boardwalk snack shop, he says. “All it needed was a piece of wax paper so the oil doesn’t drip through.”

Though the “Harriet Cole” specimen was eventually outmoded as a cutting-edge tool for instruction, it never stopped being a startling feat—and medical students have spent at least a century attempting similar exercises, sometimes setting out expressly to emulate this one. Two medical students in Kirksville, Missouri, dissected and mounted a nervous system in the 1920s—but not much is known about their method, either. Inspired by a postcard of Weaver’s work, students in the Modern Human Anatomy program at the University of Colorado School of Medicine recently tried as well, and their efforts illuminate some of the challenges Weaver likely faced. Shannon Curran tackled the project in 2017, and Justin Blaskowsky embarked on a second dissection the following year, with other students pitching in to help clean and maintain the specimen-in-progress. Each dissection took around 100 hours. Both required grappling with “tiny little forceps, picking the fat and elements of connective tissue off the nerves, [and] not ripping it,” says their instructor, Maureen Stabio. The students were up against the threats of mold and desiccation, and the work was “tiny, tedious, slow,” she says. Curran and Blaskowsky tried not to nick or tangle the nerves, or muss the ones they had already exposed while cracking through the skull to access the brain. The students salvaged many peripheral nerves, but not all of them; the school is now working to plastinate the specimens to preserve them long-term. When she thinks of the image of “Harriet” and the array of nerves that Weaver succeeded in preserving, Stabio says, “I still am amazed.”

The general process of dissection in the 19th century is well documented, from the preparation of the body with a custom preservative (often including a cocktail of arsenic, salts of tartar, carbolic acid, glycerine, and water) to the method for peeling back layer after layer of skin and viscera. The Dissector’s Manual, a popular 1883 handbook written by Oxford anatomist W. Bruce-Clarke and Charles Barrett Lockwood, an anatomist at London’s St. Bartholomew’s Hospital, walked students through dissections cut by cut. The book was also reprinted in Philadelphia around the same time and offers a useful blueprint for how Weaver’s contemporaries might have approached the general task of dissection. It instructed, for instance, to inject a solution made from boiled linseed oil and red and white lead (along with turpentine varnish and sometimes wax and resin) through the aorta or femoral artery once preservatives had suffused the tissues. This tactic plumped up the vessels to help anatomists visualize the vascular system, according to an 1822 manual.

But these guides stop well short of how Weaver pulled his masterpiece off. The earliest description of Weaver’s work on the nervous system comes courtesy of Thomas, who described the process in an 1889 edition of The Hahnemannian Monthly, the school’s journal. But Thomas’s is a hazy picture, long on the basics of dissection and short on clarity about how Weaver managed to preserve delicate nerve structures while chipping or sawing bone apart. This must have been finicky work: The spinal cord—a hardy nerve bundle—is roughly as wide as your thumb. We don’t have the complete ingredients Weaver mingled in his preservatives, a full inventory of the tools he enlisted, or a meticulous record of which parts of the process proved surprisingly straightforward or especially thorny or vexing. We don’t have a precise timeline, either. As Thomas tells it, dissection began on April 9 and concluded by June, with mounting complete by September; years later, van Baun reported that the dissection alone took nearly seven months, and then it required “seventy days of unceasing, laborious, skilled work and supreme patience to get the specimen on the board,” for a total of “nine months of gruelling [sic] contest.”

Weaver is said to have spent up to 10 hours a day in his humid office, and reportedly spent two weeks just tussling with the bottom of the skull. Once “all the little branching strands … were laid bare,” The North American noted, Weaver attempted to keep them supple by swaddling them in alcohol-soaked gauze or wads of cotton, which needed frequent changing, and he covered the flimsy strands with rubber. He retrieved nearly everything but sacrificed the intercostal nerves, which run along the ribs and proved too difficult to wrangle. Weaver reportedly excised the brain but held on to the outer membrane, called the dura mater, and plumped it up with “curled hair” stuffing, stitched it closed, and returned it to the display. To showcase the optic nerves, Weaver left the corpse’s eyes in place and distended them “with a hard injection,” Thomas wrote.

Mounting the specimen—as Weaver later recalled to The North American—was far more “wearisome and exacting” than the dissection itself. Weaver apparently tacked the nerves in place with 1,800 pins, and then fixed every filament with a coat of lead paint. (Many of those pins were later removed, Thomas wrote, once the shellacked nerves dried and held their position.) In all, Weaver reportedly spent several months laboring over the body, with a break for a summer vacation. The ultimate result, Thomas wrote, was “perfectly clean and free from all extraneous tissues and smooth as threads of silk.”

It was celebrated almost immediately. The nerves went to Chicago, to the World’s Fair, with Weaver begrudgingly in tow. “Hard as the work of preparing it was, it was not so hard as the summer that I spent at the World’s Fair at Chicago, guarding and explaining it to visitors,” he glumly explained to The North American. “And not for a pot of gold would I go through the same strain again.”

The preparation—at that point not yet known by the name “Harriet”—then returned to Philadelphia, where it went on display in Weaver’s museum—the altarpiece in a cathedral to bravura dissections. “To-day,” van Baun boasted in his 1915 remarks, “in the Weaver Museum, in Hahnemann Medical College, hangs the greatest and most wonderful dissection in all the world.”

The first people to write about the dissected nerves didn’t pay much mind to the person they had belonged to. Thomas focused mainly on the finished product and Weaver’s enervating work. Seven years later, The Medical and Scientific News, a monthly bulletin for physicians, only lauded Weaver’s skill and the acclaim it accrued. The dissection represented “persistent patience and marvelous skill not heretofore recorded in the annals of practical anatomy,” the unknown author wrote, observing that such a specimen had once been “classed among the impossibilities.” In his published history of Hahnemann, Bradford, the homeopath and historian, fawned over the specimen as the “chef d’oeuvre, the masterpiece of Dr. Weaver’s trained and dainty touch.”

A woman’s name first began to appear in printed references in 1902, in that story in The North American. The unidentified reporter noted that the raw materials had invigorated the body of a woman named “Henrietta—.” That unnamed reporter described her as “about thirty-five years old, of good form and with a healthy development of adipose tissue.” The name “Harriet Cole” first appears in van Baun’s 1915 remarks. There, she’s described as “a poor, ignorant negro woman, age 36 years, with no superfluous flesh or fat.” The writer calls her “anatomically perfect.”

The dissection took place at a time when the “scientific” study of race, and racial hierarchy in particular, was raging. Though adiposity would have been of interest to anatomists (for whom less fat was preferable, because it meant less to cut through before reaching muscle, bone, and nerves), contemporary scholars have untangled the knotted relationship between discussions of fat and race. As University of California, Irvine, sociologist Sabrina Strings, author of Fearing the Black Body: The Racial Origins of Fat Phobia, writes in a recent issue of Bust magazine, fat tissue (and, by crass extension, gluttony and hypersexuality) had been linked with blackness in the popular European and American imagination at least since Saartjie “Sarah” Baartman, a Khoikhoi woman from Cape Town, South Africa, was exhibited by showmen in France and London as the “Hottentot Venus” in the late 19th century.

Over time, the story began to be that Weaver hoisted his subject to greatness. In his notes, van Baun wrote that the woman called Harriet Cole “had greatness and world-renown forced upon her after death, by yielding up her entire Cerebro-Spinal Nervous System under the deft touch of the World’s greatest Anatomist.” The implication is that Weaver took a nobody and made her important, even immortal.

When another Hahnemann physician, George Geckeler, restored the mounted model in 1960, LIFE magazine devoted a splashy photo spread to the effort. The writer recounted how a scrubwoman who had been ignored by everyone in the laboratory “stared in fascination at cadavers” and “eavesdropp[ed]” on lectures. She osmosed the chatter, the author continued; Harriet supposedly “took to heart [Weaver’s] complaints about a shortage of corpses” and “willed her body to him.” There’s no indication of how the writer gleaned this information—this supposedly intimate understanding of a long-dead woman’s perceptions, thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. It seems that “no one went back to fact-check” the basic story, Herbison says. “Whoever said it first, that’s the thing that you use.” Details carry over from one story to another like sprawling arithmetic.

One photograph accompanying the LIFE story shows Geckeler stooping so his eyes align with the ones on the preparation. He scrunches his own, like someone puzzling over a painting, studying the canvas as if trying to decipher genius suspended between the fibers. By this point, the myth of “Harriet Cole” had grown to include not just Weaver’s work, but the woman herself—a lowly person made spectacular, in every sense. A fascinating object never quite or fully human, but almost looking the part.

The cadaver that would become known as “Harriet Cole” arrived at Hahnemann during a time of change for American medical schools. Over the course of the 19th century, these institutions had come to rely on the dissection of corpses for the study of anatomy, but there never seemed to be enough to go around. For much of the century, there were few, if any, legal hurdles to procuring bodies. A shadow economy arose, providing corpses pilfered from almshouses, hospitals, even graveyards.

To meet the demand for cadavers without risking legal action or provoking public outcry, wrote Carnegie Mellon University historian David Humphrey in a 1973 edition of the Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, “the safest way was to steal the dead of groups who could offer little resistance and whose distress did not arouse the rest of the community.” People at the bottom of the social strata were at particular risk of ending up on an anatomist’s table, and “Blacks and white paupers provided attractive targets,” Humphrey continues. (Zimmerman, the medical historian, points out that the same demographics, including Irish immigrants, were also disproportionately likely to contract and die from communicable diseases such as tuberculosis, which thrived in uncomfortably close quarters.)

The practice of mainly white American physicians honing their skills on the bodies of disenfranchised people is a legacy of slavery, and an imagined racial hierarchy that propped up white supremacy. “It is one of the ironies of medical history that, although Blacks were generally regarded as ‘inferior’ or even ‘subhuman,’ their corpses were considered ‘good enough’ to use in the instruction of human anatomy,” write anthropologists Robert L. Blakely and Judith M. Harrington in Bones in the Basement: Postmortem Racism in Nineteenth-Century Medical Training. In her book The Price for Their Pound of Flesh, The Value of the Enslaved, From Womb to Grave, in the Building of a Nation, University of Texas at Austin historian Daina Ramey Berry describes how the cadavers of enslaved people came to hold a “ghost value,” based on their appeal to 19th-century doctors and medical students—a final way to extract work from a person no longer living.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, public protest around body-snatching was loud and passionate: “Between 1785 and 1855, there were at least seventeen anatomy riots in the United States, and numerous minor incidents, affecting nearly every institution of medical learning,” writes historian Michael Sappol in A Traffic in Dead Bodies: Anatomy and Embodied Identity in Nineteenth-Century America. Outraged over stolen corpses, citizens “reclaimed their dead, mobbed body-snatchers and anatomists, [and] stormed medical colleges,” Sappol notes.

By the middle of the 19th century, both to satisfy demand and quell outrage sparked by these body procurement practices (particularly when they happened within wealthier, less marginalized communities), states began passing anatomy acts to outline legal avenues for acquiring bodies. The Pennsylvania state legislature passed one in 1867. Also called the Armstrong Act, it entitled anatomists to any unclaimed bodies that would have required publicly funded burial in Philadelphia or Allegheny counties. But it didn’t come close to supplying enough bodies for the city’s medical training industry.

In Philadelphia, even after the 1867 law, Humphrey writes, anatomists at Jefferson Medical College, where Weaver had studied, “and probably other medical schools … tried to make up the difference by using bodies snatched from Lebanon Cemetery, a Black burial ground in Philadelphia.” (One of the very architects of the 1867 act, William S. Forbes, was later charged for a grave-robbing scheme, but ultimately acquitted.) Across Pennsylvania, accounts of medical students canvassing nighttime graveyards continued to be splashed across newspapers as front-page scandals.

Writing about grave-robbing and dissection in the Penn Monthly in 1879, a physician named T. S. Sozinsky asserted that, while “body-snatching, in all its forms, almost universally is regarded with a superlative degree of abhorrence,” many bodies dissected across the country each year were still obtained illegally. Sozinsky alleged that anatomists in Michigan, Illinois, and Pennsylvania copped to knowingly dissecting corpses procured from potters’ fields and almshouses and sold for anywhere from $5 to $30 apiece. (In Pennsylvania, convicted grave robbers faced fines of between $1 and $50, and a possible prison term that couldn’t exceed one year, Sozinsky added.) By 1883, five years before Weaver dissected the nervous system that would become “Harriet Cole,” Pennsylvania had passed a more comprehensive act. This created an administrative board to allocate unclaimed bodies to schools based on enrollment, and became a model for other states.

There’s no evidence to suggest that the bodies Weaver dissected at Hahnemann had been taken outside of the law, but the exploitation of Black bodies—alive and dead—looms over the story of “Harriet Cole.” Even if everything was above board legally, Zimmerman observes, the action can sit uneasily in the fissure between what is legally permissible and what is morally defensible. (“Can we confirm that she wanted to donate her body to science?” Zimmerman asks. “No, we cannot.”) The story of a woman named Harriet Cole promising her body to a dissector can be a difficult one to take at face value—especially since, at the time, the practice was deeply controversial and there were few formal ways to donate one’s body.

“Most doctors at the time thought it was crazy not to do dissection because the good for society outweighed the good of a body decomposing in the grave,” says James R. Wright, a pathologist and medical historian at the University of Calgary. Many patients in 19th century New England, on the other hand, were squeamish about the prospect or baldly horrified by it. Says Rana Hogarth, a historian at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and author of Medicalizing Blackness: Making Racial Difference in the Atlantic World, 1780-1840, “Physicians saw [dissection] as essential, but, for most of the public, nobody wanted this fate.” Writing in the Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine in 1973, Humphrey, the Carnegie Mellon historian, explained that in the popular imagination of the 1800s, dissection would have been figured as “a degrading and sacrilegious practice, an act to be inflicted on an outcast as punishment—much like the medieval rite of drawing and quartering a criminal.”

Some laypeople argued that a living patient was better off being treated by someone who had seen the body’s inner contents up close. In 1882, The Christian Recorder—the newspaper of the African Methodist Episcopal Church—endorsed dissection, suggesting that it would be foolish for anyone to seek treatment “at the hands of a man who had not gone through the mysteries of the dissecting room.” Still, even those who supported the notion of dissection typically did not want to entertain the thought of it happening to anyone they loved. The anonymous author of that article in The Christian Recorder skewered grave robbing on moral grounds and suggested that doctors be offered the bodies of executed murderers and anyone who died by suicide.

The few people who expressly permitted, or even beseeched, doctors to cut into them after death tended overwhelmingly to be white, wealthy, and accomplished men. By 1889, the new American Anthropometric Society, headquartered in Philadelphia, began compiling the brains of physicians and public intellectuals who embraced the ideas of phrenology, which correlated intellectual feats with cranial attributes. These donors were keen to join the organization’s “brain club” as a way to further the field while also valorizing themselves.

And in the medical realm, consent was slippery. William Osler, a founding professor of Johns Hopkins Hospital, was known to solicit family approval before giving cadavers to his students—but he was also famously dogged in his pursuit of that permission, and in a 2018 article in the journal Clinical Anatomy, Wright, the University of Calgary pathologist, notes that “autopsy consent and organ retention abuse was not uncommon in late-19th century Philadelphia.” In a 2007 Academic Medicine article about the uptick in body bequeathal in 20th-century America, Ann Garment, then a medical student at New York University, and three coauthors note that turn-of-the-century body donation was uncommon enough to make the news when it happened. The New York Times picked up the tale of Thomas Orne, a wealthy Maryland horse dealer who pledged his body to Johns Hopkins in 1899. In 1912, 200 New York City physicians also vowed to donate their bodies for dissection in an effort to erode the stigma around it.

In a doctoral dissertation about Pennsylvania’s dissection laws, historian Venetia M. Guerrasio writes that the apparent first person to contact the state’s Anatomical Board to pledge her body to science—a woman named Minnie Faber—did not do so until 1922, when she indicated her intent to leave her body to Hahnemann. Popular interest in donating one’s body for medical purposes surged when the Eye-Bank of New York began soliciting corneas in the early- to mid-20th century. Pennsylvania’s Anatomical Board codified procedures for willed bodies in 1952, Guerrasio writes; the country’s first Uniform Anatomical Gift Act, setting the terms for bequeathing one’s body, was introduced in 1968, on the heels of the first successful heart transplant.

“I am aware that there have been men, [the philosopher Jeremy] Bentham for instance, who have voluntarily willed their bodies to be dissected, but they have been extremely few,” Sozinsky recounted in 1879. Opting in was far from commonplace. “The ‘Harriet Cole’ story, if correct, is likely very unusual,” Wright notes. If a flesh-and-blood Black woman named Harriet Cole consented to her own dissection more than 130 years ago, she would have had very little company.

For the past few years, McNaughton, Zimmerman, Herbison, and their colleagues have been chasing a ghost. Building on the work begun by other staff before them, they are looking to lay out a reliable paper trail that can anchor the swirling story in historical fact. To do it, they’re trawling through records and archives in pursuit of evidence of the formerly living, breathing Harriet Cole.

Archivists are hungry for low-hanging fruit, which includes digitized census records, newspaper articles, and other materials easily summoned by straightforward searches. Then there are the documents that are trickier to find: the birth certificates, the death certificates. There’s also the chance of finding a needle in the archival haystack—a mention in meeting minutes, maybe, or a church directory, or something else that could make the picture of someone’s life a little less incomplete. Across these categories, there are likely to be frustrating gaps in the record; ancestral administrators didn’t think to leave a trail of crumbs for people like McNaughton, Zimmerman, and Herbison to follow, decades later, from an office in a sleepy corner of Philadelphia. Sometimes there are incomplete answers. Sometimes there are nearly none at all.

In 2018, McNaughton found Census records indicating that a Black woman named Harriet Cole lived in Philadelphia in 1870, and worked as a domestic. She was listed as 25 years of age, and unable to read or write. Plunging into the city archives, Zimmerman rustled up old patient intake and discharge records that revealed that a woman named Harriet Cole had been hospitalized several times over the course of two years, including at least once for tuberculosis. (Those records report that she was unmarried, childless, and born in Pennsylvania, though Zimmerman points out that there’s no way to confirm the historical accuracy of those annotations. A Black woman who died in her thirties in 1888 would have been born into a country where slavery was still widely practiced, and because the once-living Harriet Cole remains elusive, researchers haven’t determined whether she or her family were enslaved—a fact that could cast doubt on some of those notes. “She might not know her exact birthplace if she was born a slave,” Zimmerman says.) McNaughton also consulted a death certificate from the Blockley Almshouse (later rechristened as Philadelphia General Hospital), which revealed that a Black woman named Harriet Cole died from phthisis—or pulmonary tuberculosis—on March 12, 1888, at the age of 36, and was buried at Hahnemann Medical College a week later. (Another institution’s name was written and then scribbled out in the field reading “name of deceased,” correcting what Zimmerman calls a “19th-century typo.”) The fact that the hospital was listed as the place of burial suggests that the body was handed over for dissection, adhering to the protocol of the day, Herbison says. The school was “the final resting place, as far as the law is concerned.”

But there were enough inconsistencies to give the researchers pause. The ages don’t quite add up—the Harriet Cole in the 1870 census would have been 43 in 1888—but one or both could be wrong, there could have been several women with the same name, or the woman named Harriet Cole might have had a murky idea of her precise age. These documents establish that a Black woman named Harriet Cole lived and died in Philadelphia toward the end of the 19th century, but they don’t show that she worked for Weaver, or that she promised her body to him, or that the nerves on display are hers.

McNaughton dug deeper, into minutes from meetings of the school’s faculty and board. She encountered a maddening gap spanning the entire window she was looking for. But even if the records had been there, there’s no guarantee a low-income Black domestic laborer would have been mentioned. “Faculty members get listed, but any other staff is completely haphazard, more on the side of not being captured whatsoever,” Herbison says. “You might have a secretary that worked there for 20 years who never gets named.” Records from the 1800s are scattered to begin with, and tend to prioritize “big, important people,” McNaughton says. Information about lower-level workers didn’t simply “fall through the cracks,” Herbison adds. “Systematically, it was absent.”

As far as the archivists know, there’s no surviving catalog of the specimens that once filled Weaver’s museum. Conceivably, such a volume might have included brief biographical sketches of the people whose bodies he dissected. Some of the entries in pathologist and curator William Pepper’s 1869 catalog of the specimens at the pathological museum at Philadelphia’s Pennsylvania Hospital, for instance, went into fine-grained detail about the deceased’s age, race, profession, and cause of death. A scapula in the collection, readers are told, came from a John Mealy, a 30-year-old who died nine days after being admitted to the hospital on June 2, 1866, with a wound stemming from a musket discharging into his left shoulder. No such paper trail exists for a Harriet Cole.

If McNaughton and Herbison could design their ideal evidence for Harriet Cole as the story portrays her, it would be two entries in faculty minutes—the first describing Harriet’s position at the school and her home address (to corroborate Census records), and the second saying that she had died of tuberculosis (to confirm the death certificate) and had explicitly willed her body to Weaver. “We’re not even close to that,” Herbison says.

When the obvious sources of information failed, McNaughton went fishing. “I just kind of walked through [the stacks] and opened boxes,” she says. “Like, ‘Come to me!’” She sifted through a jumble of ephemera from the late 1800s—receipts, bills, canceled checks, and more—that a night watchman reportedly stumbled across in the 1980s after being spooked by a strange sound coming from a closet. McNaughton rifled through each aging, yellowing bit of hay in the stack, but encountered no needle.

Herbison suspects it’s possible that the nerves may have come from someone else entirely, and the Harriet Cole name was used to fill in a historical memory gap. In this scenario, the person’s name was forgotten, or maybe never recorded—then, as the dissection became famous and people clamored for more information, someone went trawling for a likely candidate that fit the general profile of age, sex, and race, in service of telling a good backstory. But there’s even less to suggest that version of the story, beyond elisions, inconsistencies, and hunches. “I’m a little more likely to believe that this is Harriet than to believe that it was a made-up name … that was applied to her at a later date. But, like, my confidence … ” Herbison trailed off. “I’m a good, solid 40 percent sure of that.”

The archivists haven’t yet exhausted all avenues for matching the nervous system with the person who carried it through the world. The researchers could recruit a genealogist for a deeper dive, or peruse church records and more crannies of the city archives. But Herbison remains fairly confident that any definitive documents, if they exist, are floating somewhere inside the school. Still, there’s only so much the team can do to stay on the hunt: McNaughton is now off the case, and Zimmerman is a part-time employee. Herbison wonders if they’ve reached a point where they’ll stall again and again—a cycle of cul de sacs and dead ends. “Looking and looking and looking,” Herbison says, “finding nothing and nothing and nothing.”

Fastened forever in place, the nerves themselves may have some information to share about the person who might have been named Harriet Cole. In theory, at least, a forensic examination could confirm the sex of the person whose remains are in the glass case, though any DNA is likely to be broken down beyond reliability after decades covered in preservatives and lead paint, according to Dadna Hartman, manager of molecular biology at the Victorian Institute of Forensic Medicine in Australia. “Given the age of the biological material, and the treatments it has undergone since its recovery, I doubt very much that any DNA would survive, and if present it is likely to be highly degraded,” Hartman says. The best chance at extracting any, Hartman adds, would be with the help of a laboratory that specializes in ancient DNA—the kind wrested from prehistoric teeth embedded in permafrost or supremely desiccated corn cobs. Such a lab would be “designed to process old or severely compromised samples,” Hartman says—but there’s no guarantee the sample would yield anything usable. That uncertainty—as well as the cost, coupled with the risk of damaging the display, which has been sealed since the 1960s—has kept anyone from seriously considering this approach.

There’s also a chance that descendants could help bring the story into focus. The high-profile case of Henrietta Lacks—the 31-year-old Black woman whose cancer-ravaged cervical tissue was harvested by doctors at Johns Hopkins without her knowledge in 1951 and whose cells became, as a Nature editorial put it, “a workhorse of biological research”—is an analogue of sorts, with several major differences. Bearing photographs and memories, Lacks’s descendants were able to conjure a picture of her as something other than a patient from whom a sample was collected in the era before informed consent: They described her as a devoted mother who loved spaghetti, dancing, and crimson-hued nails. Lacks’s descendants were eventually consulted about the publication of the cells’ genome. In 2020, at least one biotech company paid reparations to the family.

In some other museum collections, human remains—many of which were amassed during periods of colonial plunder—have been returned to descendants. Repatriation work is ongoing with Native American remains, and the remains of Maori and Moriori ancestors have returned to New Zealand from museums in England, America, Canada, Germany, Sweden, and more. In January 2021, Harvard—which houses the remains of 22,000 individuals—convened a committee to research 15 Black people who were likely alive when slavery was practiced in America, and whose bodies now reside at the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology. That committee will eventually introduce guidelines about collecting, displaying, and caring for human remains. But there are few, if any, precedents for returning a medical school specimen to a family. If “Harriet Cole” had any relatives, the researchers haven’t found them. And, so far, no one has come looking.

The Drexel team plans to tweak the wall text, upending some of the lore that has surrounded Weaver and his legacy for more than a century. The researchers will highlight the doubt about the veracity of the story, and Zimmerman also hopes to expand and revamp the exhibition space for the Weaver preparations. The COVID-19 pandemic delayed this work, because the researchers planned to convene informal focus groups with high school classes that encountered “Harriet” on medicine-focused field trips. For the most part, in 2020, those groups didn’t come. “It’s disappointing, because we were plodding away, heading toward something better than what’s been on the wall for some time,” Herbison says. “Now we’re a year behind, at least.”

The lore around “Harriet” has shifted over the years, a mirror to the preoccupations of the moment. “The mythology has changed along the decades to mesh more with the gestalt of society,” Herbison says. The person became a prop. When Weaver was a hero, she was his muse, and, in death, a tool for teaching future generations of doctors. She was “a real person, and everything written about her is making her like an accessory to Weaver,” McNaughton says. As the school continued to mint new physicians, the specimen became a mascot of sorts; graduates recalled it with affection, like an affable colleague they passed in the hallway. Today, as historians reexamine medical history (and history in general) with an eye toward foregrounding voices that don’t often appear in official documents, “Harriet” is a reminder of deep crevices in the record, and the stories that slip into them.

Those voices, Harriet’s voice, may always be hard to find. They’re muffled by archival absence—silence, where there should be a loud, constant hum. “You think of archives as this place where, you know, there’s everything,” McNaughton says. “Yeah. No.” Says Herbison, “There’s more not there than there.”

For now, archivists and historians can narrate the searching—the disappointments, the puzzles, the hope that a bit of evidence is out there, somewhere, waiting to be pulled from a shelf. Meanwhile, visitors continue to pause when they meet “Harriet.” The specimen arrests them and holds them there, their own reflections frozen, for a moment, in the glass.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook