Before Mace, a Hatpin Was an Unescorted Lady’s Best Defense

Accessories to assault.

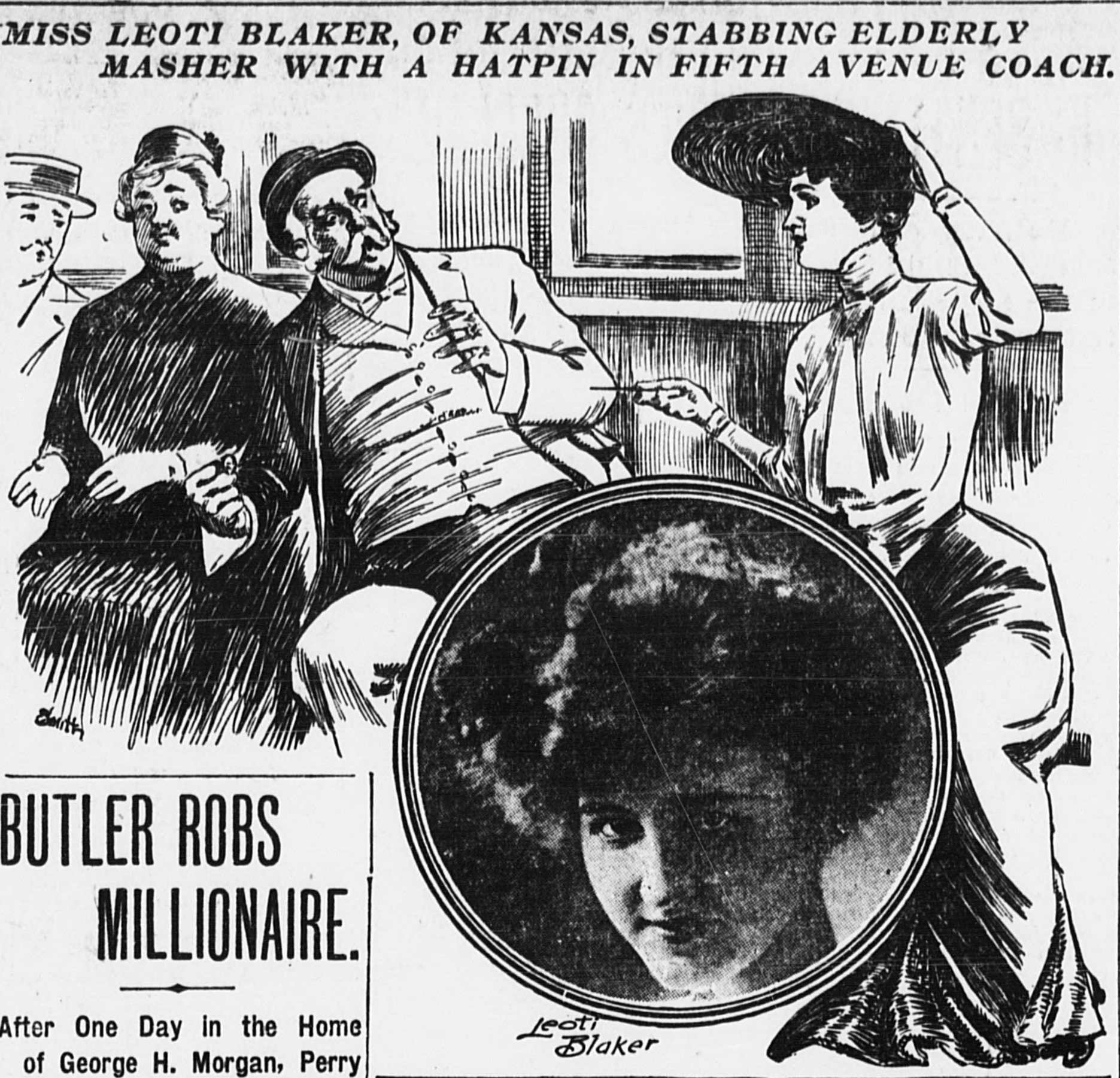

There were once, among the rogues’ gallery of men who harass women in public, disreputable fellows known as mashers. The masher took a lady’s arm, the masher took liberties, the masher might, with the slightest provocation, take advantage. He approached a woman he did not know, to ask her to a dance or to ask if he hadn’t met her somewhere before. The masher, above all, the Scranton Truth explained in 1914, was “just a plain cad … a coward, too, for he knows that an unescorted girl can only express her resentment by ignoring him.” But women had another tool in their arsenal to swiftly prick and deflate the masher’s inflated ego: the hatpin.

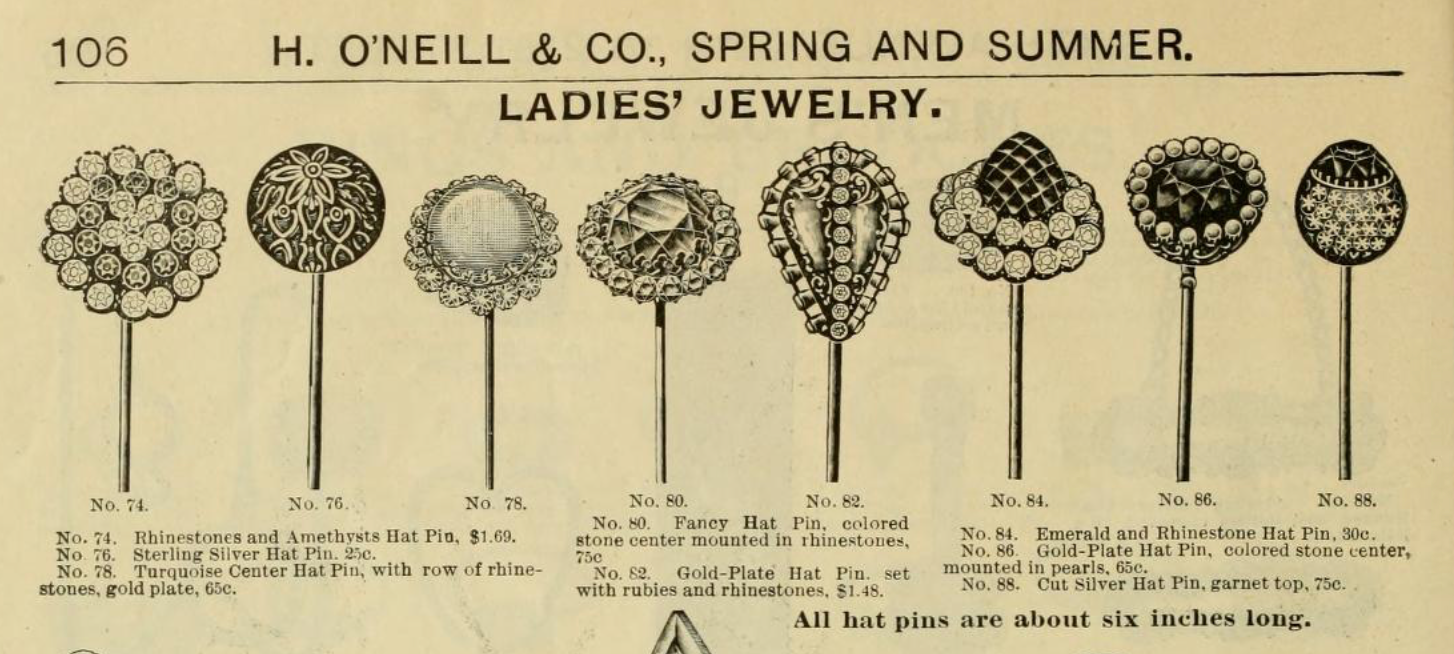

Between the late 1880s and the early 1920s, advertising was on the rise and increasingly targeting women. Among the alluring consumer goods pitched to them were hats: the more elaborate and precariously perched, the better. At the same time, women’s hairstyles began to climb higher and higher. They grew their tresses long, then pinned them up, sometimes stuffing them with bits of false hair or cloth. This, reported The New York Times, made it “impossible to fit a hat to a lady’s crown.” By 1901, fashionable hats had grown into towering monstrosities of taffeta, silk, ribbons, flowers real and fake, ostrich feathers, and even artificial fruit. Affixing these edifices to those hairstyles required stout hardware, sometimes of six, eight, even 10 inches in length. All the ingredients were there—ridiculous hair, even sillier hat—for a perfect hatpin storm.

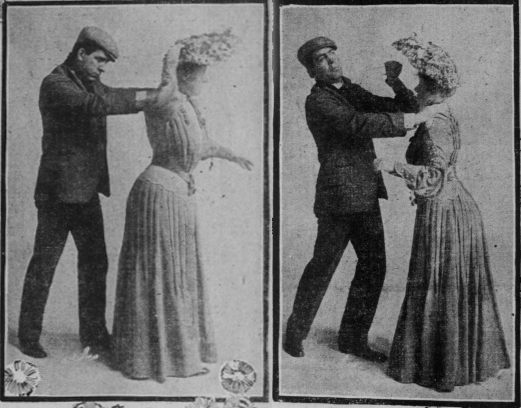

This period also saw more women were walking alone or in unaccompanied groups, which some men found either morally affronting or desperately alluring. Unchaperoned women began to experience sexual harassment on the street or on public transportation more than ever before. But, for “perhaps the only time in American history,” writes Kerry Segrave, in The Hatpin Menace: American Women Armed and Fashionable, 1887–1920, “virtually all American women went out and about armed with a deadly (though legal) weapon.” That weapon attached their hats to their hair—and it was so effective that within a decade, proposed legislation to curb these accessories to assault had bubbled up across the United States.

Initially, hatpin injuries were relatively innocent, and occurred in the crush of train carriages or busy streets. They were hazards for men wooing even approving women, said the Times. “Nonetheless, young men with streaky scratches on their right cheek have been turning up at their places of business of late with a variety of explanations savoring of more ingenuity than truth as to how they won their wounds; and most engaged young girls have a hat for evening walks that is independent of hatpins.” But women swiftly realized that the oversize pins they carried could also be used to fend off undesirables. Injuries from this kind of use were usually “not serious, although very painful,” the Times reported—and served as a swift lesson to a masher’s wandering hands.

Hatpins were used to help pin down a burglar, for example, or by a “plucky typewriter” facing two robbers on a Chicago train. (They “jumped off the car without having got anything except wounds,” the Times said.) As a method of self-defense, they gave women independence. In Chicago, in 1910, a woman wrote this letter protesting potential legislation: “I always feel safe going home late at night with a hatpin available for protection. Before leaving a streetcar, I always carry a hatpin ready in my hand until I am safe within the door of my house.” She added: “Thousands of other women undoubtedly can speak from their experience of how a stout hatpin has been an effective defence in times of danger.” A raunchy music hall ballad of the time, “Never Go Walking Out Without Your Hat Pin,” echoed the sentiment.

My Granny was a very shrewd old lady,

The smartest woman that I ever met.

She used to say, Now listen to me, Sadie,

There’s one thing that you never must forget.Never go walking out without your hat pin.

The law won’t let you carry more than that.

For if you go walking out without your hat pin,

You may lose your head as well as lose your hat.…

Never go walking out without your hat pin.

Not even to some very classy joints.

For when a fellow sees you’ve got a hat pin

He’s very much more apt to get the point.

Men generally loathed these hats, and the pins that held them in place. They were cumbersome, and impossible to see over in crowds or theaters, churches, concerts, or any other place of entertainment. Even under innocent circumstances people were at risk. In crowds, cheeks were scratched, eyes narrowly avoided gouging, and the tiniest of accidental scratches could lead to nasty infections. Even death was not unheard of, whether as a result of blood poisoning, or worse. On February, 1898, Parisian tourist Bartholomew Brandt Brandner was murdered with a hatpin in a Chicago saloon: “a small puncture which began near the corner of the left eye and expanded far into the interior of the skull.” The details of the scuffle died with him.

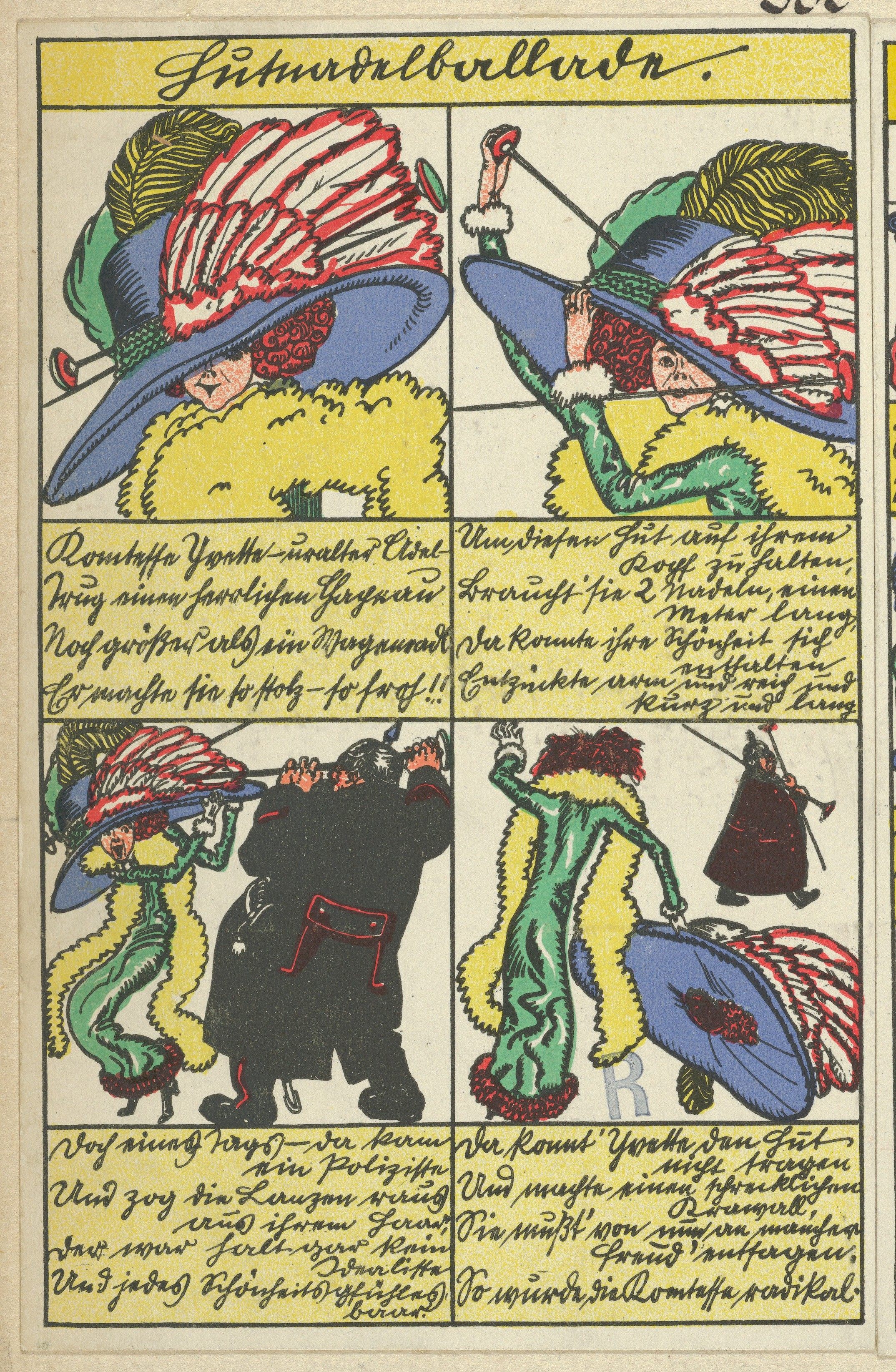

Something had to be done. Churches and theaters began to put up signs instructing people not to wear large hats inside. By 1910, hatpins had become a national, and then international, threat. Lawmakers from Chicago to Kansas City and Hamburg to Paris began to write legislation that limited hatpins’ length or demanded that women put protective sheaths over the ends. In Chicago, women could be fined $50 for wearing hatpins more than nine inches long. Similar ordinances were passed everywhere from Milwaukee to Pittsburgh to New Orleans.

But the laws were somewhat ineffectual. “Even when this was accomplished, the police were said to be too bashful to approach women in the streets to enforce those laws,” writes Segrave. “Men were genuinely trepidatious about taking public transit, as all those protruding hatpins threatened and endangered them.” A 1917 article in the Chicago Day Book, observing that men could get women arrested for their rogue hatpins, instead concluded chivalrously, “Far be it from us to pick on the ladies. Let’s try and see that they all get a seat so they won’t have to swing around on a strap.”

Furious women often refused to abide by the laws. In November 1912, 60 women in Sydney, Australia, were arrested and sent to jail over refusing to pay the fines for their overlong hatpins. “They declare that the law prohibiting protruding hatpins is ‘iniquitous and unnecessary legislation’, and they will not submit to it,” wrote the Times. “What is more, if they are kept in jail long, they will starve themselves to death. So there, now!” It is no coincidence that the rise of the hatpin self-defense coincided with the campaign for women’s suffrage: Walking the streets safely began to be seen as a right not to be infringed upon.

For all their utility, the hatpin was most of all an unexpected consequence of the extraordinary hat. Without the headwear, the pins were just weapons. Fashionistas of the time favored hats with real plumage, which led to the slaughter of thousands, even millions, of birds every year. Lobbyists called for an end to this needless killing, lest the birds go extinct. In 1918, the Migratory Bird Treaty Act made it illegal to kill, sell, or transport certain birds and feathers. It was a hatpin through the heart for these millinery miracles. By the 1920s, women were bobbing their hair short and wearing cloches, turbans, tam o’shanters. Hatpins were largely retired—and mashers breathed a skeevy sigh of relief.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook