Help Curate This Vast Trove of Kitchen-Table Remedies

The Archive of Healing includes hundreds of thousands of folk healing traditions from six continents.

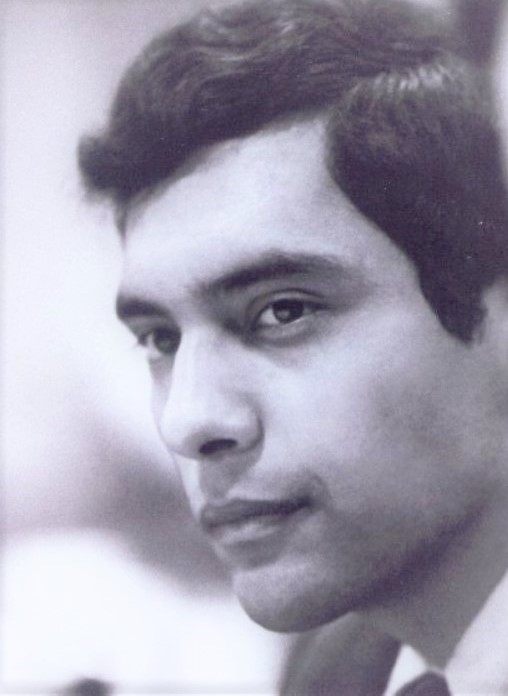

Héctor Calderón was 19 in 1965, when he was hired to help compile what would later become the Archive of Healing. He had entered the University of California Los Angeles hoping to become an accountant. That all changed when he started working for Professor Wayland Hand, the Director of UCLA’s Center for the Study of Comparative Folklore and Mythology, who had just launched an ambitious project compiling folk remedies from around the world. The remedies ranged from folktales and incantations to recipes and sayings around food

Calderón spent hours as a research assistant digging through ethnographic studies, noting down each remedy on an individual notecard and passing them to Hand to file in huge wooden trays. Calderón also collected his own Mexican-American family’s folk traditions for a class project. “Why do you want this stuff?” his family asked, surprised their knowledge was interesting to academics. At the time, of UCLA’s 25,000 students, only 50 or 60 were Mexican American. Calderón, too, was initially shocked that working-class people’s traditions would be valuable to a university professor. But Hand was an enthusiastic mentor, and Calderón quickly caught the countercultural energy of the 1960s university. “No way could I do business anymore—that wasn’t my world,” he says.

Calderón ended up going to graduate school in literary studies. Hand kept quietly working on the Archive. Upon his retirement, he passed the data to another professor, Michael Owen Jones, who got a grant to digitize the material in 1996. After Jones retired, the project sat in limbo, preserved on UCLA’s servers, for years.

Half a century after Hand started it, a new group of UCLA researchers has made the Archive of Healing available to the public. Now a searchable database, the Archive of Healing includes 700,000 pieces of data, digitized from more than 1 million index cards, ranging from folk sayings and rituals to incantations and recipes. The archive represents 50 years of research spanning six continents, two centuries of ethnographic study, and 3,200 journal articles. According to the current director, David Delgado Shorter, Professor of World Arts and Cultures/Dance at UCLA, it’s one of the five largest archives of healing-related knowledge in the world. The UCLA archive is unique in the breadth of cultures it represents—and in its approach to that representation.

Up to a third of the archive, says Shorter, who has been preparing the archive for publication since 2012, consists of edible medicinal recipes. For most cultures, the boundaries between food, medicine, agriculture, and spirituality were much more fluid than in modern Western knowledge systems. Until the 1800s, European and North American cookbooks contained recipes for both food and household medicine. In many cultures, women and feminine people are the primary bearers of this knowledge. “Women cooking is actually where a lot of culture continues from one generation to the next,” Shorter says.

You can see this reflected in the Archive of Healing. Search for corn, for example, and you’ll find that a Mexican healer in 1922 recommended corn-silk tea for bladder problems. She would only share the recipe with a female researcher, likely considering it women’s knowledge. Meanwhile, New Mexican midwives in 1964 recommended blue corn harinea, a finely ground porridge, as postpartum food. These recipes reflect the central role corn plays for many North American Indigenous people, many of whom consider corn a member of their family. Cyndy Garcia-Weyandt, a professor at Kalamazoo college who was advised by Shorter, says that for the urban Wixárika Indigenous families she works with, “Our Mother Corn was not only cultivated for healing practices, but also to maintain a relationship,” and to support local ecosystems. “Food is medicine maintaining the balance between us and the environment.”

Healing recipes and food wisdom are often surprisingly consistent across cultures. Dozens of entries hinge around pregnant mothers’ food cravings. Sources in San Diego and in the Philippines in the 1970s believed that pregnant mothers should be given what they crave or they’ll miscarry, while a source in 1950s Salt Lake City said that if a pregnant mother doesn’t get the food she craves, her child will crave the same food. My great-great grandmother from Naples, meanwhile, used to say that the milky sap from fig trees was a good cure for warts. A quick search in the Archive shows that people in 1958 Spain, 1962 Arkansas, and even the Bible had similar beliefs.

Curating this vast trove of knowledge has been no small task, but Shorter is well-suited to the job. “I was raised by my great grandmother, who was an untrained midwife healer woman,” says Shorter. For the majority of his academic life, he documented linguistic and healing traditions with the Yoeme people, an Indigenous group in Mexico, and developed a wiki-style website documenting their language.

Around 2012, Shorter got a message from a University of California librarian, who was thinking of deleting a previously unnoticed digital archive. Was it worth keeping? “I said, ‘Oh my god, this is absolutely valuable,’” Shorter says. The library made him guardian of the data.

Shorter’s first worry was appropriation. Much of the Archive of Healing’s contents are sacred to the cultures that produced them. Because much of it was collected at a time when anthropologists were less sensitive to appropriation in ethnographic fieldwork, Shorter was unsure whether the contributors had truly consented to their healing practices being shared. He worried that a pharmaceutical or food company would mass market or patent the information.

So Shorter and his students got to work. They recruited a group of practicing healers to a newly formed advisory board to help oversee the project. They spent hours poring over spreadsheet rows (“We’re talking about hundreds and hundreds a week,” Shorter says), leaving cures that were already common knowledge, but making those that were not well-known unsearchable. Shorter plans on creating special administrator accounts for people from the cultural groups that produced each piece of sensitive knowledge, so they can ultimately control whether that information is visible to the public.

Site administrators removed knowledge they considered racist, sexist, homophobic, and transphobic. (Researchers specializing in histories of discrimination can access this knowledge through Shorter.) They then categorized each piece of knowledge based on how safe it was for public use, marking it as appropriate for all audiences, only for healers, or only for academic researchers.

This sensitive category included many recipes for abortifacients, says Alex McKinley, Assistant Director of the archive and a UCLA senior majoring in gender studies. The Archive includes dozens of beliefs around what people with uteruses should eat to prevent pregnancy. New Mexican women in 1935 drank vinegar; Algerian women in 1915 ate saffron; Slovakian women in 1946 ate walnuts. Other foods, like carrot seeds boiled in wine (London, 1809) and baked rabbit vulva (the former Czechoslovakia, 1946) were believed to encourage conception. Researchers marked several recipes for herbal abortifacients, many of which are poisonous and should not be ingested, as sensitive. McKinley authored a special section with resources for users seeking to learn about safe abortion.

For centuries, Western academia has largely operated on the assumption that all knowledge can be acquired—a project embodied, for example, in the 18th century invention of the encyclopedia. But there was a violent underbelly to this aspiration: European colonizers often collected and exploited colonized people’s knowledge in order to control them. For example, colonial British scientists and ethnographers collected cannabis-related culinary and medicinal knowledge in India only to criminalize use of the traditional drug.

In contrast, the Archive of Healing is organized to acknowledge that, in many cultures, sacred knowledge is not considered appropriate for all people. Shorter quotes one of his Yoeme collaborators. “In my day it was not your job to know everything,” the elder said. “You were told things that you were meant to know.”

Indeed, in certain healing traditions, the very efficacy of a cure depends not just on the plants used, but on the user’s relationship to nature, their community, and the spiritual world. Graduate student Julie Gaynes, one of Shorter’s advisees, is documenting women’s spiritual healing practices in Indonesia’s Solor Archipelago. She tells a story of a healer she works with, whose ancestor appeared in a dream to grant her permission to use a particular healing plant. When the healer’s daughter tried to pick that plant to help heal someone, the daughter became ill. Gaynes’s collaborator said this was the ancestor’s reprimand for taking a plant she did not have permission to use.

Advisory board member Edgar Fabián Frías, an Indigenous Wixárika artist, curator, educator, and therapist who has guest lectured for Shorter, says this is one of the strengths of the archive. Not all knowledge will appeal to all users—and that’s a good thing. “Maybe if I don’t resonate with it that’s okay, because it’s not meant for me,” Frías says. “Sitting with that complexity and that multiplicity is really powerful.”

Since the Archive went live a few weeks ago, public response has been enthusiastic. Shorter has received dozens of messages from healers, researchers, and laypeople looking to share information from their own traditions. The archive will open to user submissions later this year, and the team plans to set up Wikipedia-style categories of users who can continue to flag information based on its sensitivity.

For advisory board member Amanda Yates Garcia, public enthusiasm for the Archive is part of a deeper contemporary desire to connect to culinary and healing practices—like pandemic-era gardening or bread-baking—that defy commodification. “People today are really hungry for a spiritual practice that honors the earth, that honors queerness, that honors different forms of family aside from the nuclear family, that embraces community, that holds as one of its central tenets and principles an allegiance to justice, that is essentially anarchist in nature,” says Yates Garcia, who is a practicing witch in the West Coast tradition of Reclaiming. “Especially Millennials and Gen Z, because they’re seeing the world torn apart by ideologies that don’t have these principles.”

The Archive is also part of a movement among some academics away from treating knowledge as property to be patented or kept behind a paywall, and toward honoring it as a living part of human lives and communities.

This is certainly true for Calderón, who says working on the Archive helped teach him that his culture, too, deserved recognition and study. When working on the Archive one afternoon 60 years ago, Calderón saw a copy of Americo Paredes’s With His Pistol in His Hand, a founding text in Mexican-American cultural studies. That book—accompanied with the validation he received from Hand—opened a sense of possibility: Perhaps there was a place for him in the academy. Calderón went on to become one of the leading scholars of the then-nascent field of Chicano studies.

When Calderón saw an article about the Archive of Healing earlier this year, that early sense of wonder came flooding back. “It was like a flash,” he says. Calderón reached out to Shorter, who invited him to join the Archive of Healing’s advisory board. Now Calderón stewards the very body of knowledge that, as a 19 year old, helped set him on his life’s path.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook